DALLAS — Walter Bonner goes to the Costco off Coit Road in North Dallas, not far from where he grew up. And as he drives down from his home in Garland, he sees the high-rise office buildings and the sprawling apartment complexes and the High Five highway bridges, one stacked on top of another.

And he wonders if anyone knows.

"People have no idea that a Black man owned property there," Bonner said. "It's kind of sad to me, in a way."

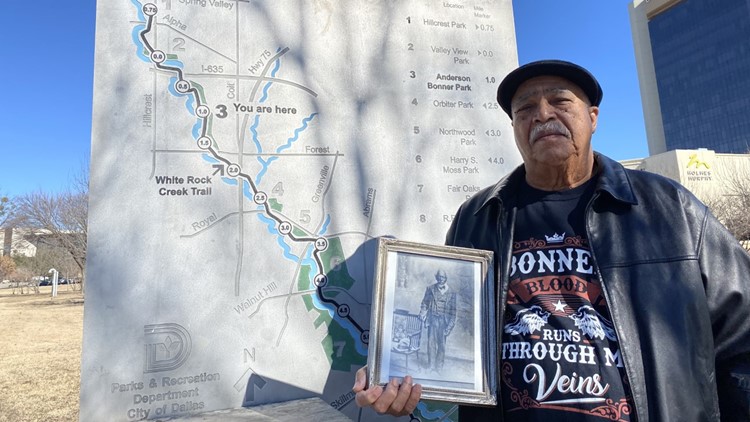

Bonner, now 78, is the great-grandson of Anderson Bonner, who was born a slave but became one of the biggest landowners north of Dallas by the turn of the 19th century.

Not much is known about Bonner. There is the single black-and-white photograph, with Bonner standing in a suit with his hand resting on the back of a chair; copies of old land records and the stories passed down through his family.

But those small glimpses into his life paint a remarkable picture.

"To think that a man could do that, after he was freed from slavery, I am very proud," Walter Bonner said. "Just think what he did. It was something great."

He was born on a plantation in Alabama in the 1830s. At some point, presumably before the Civil War, he was sent to Texas as a wedding a gift for his owner's daughter, according to the Bonner family.

He was eventually freed and settled northeast of Dallas, along White Rock Creek, near where Forest Lane cuts through Lake Highlands today.

Bonner couldn't read or write. He signed his name with an "X." But he knew how to live off the land, Walter Bonner said.

Piece by piece, he bought up property along White Rock Creek and across present-day north Dallas, near where U.S. 75 meets the LBJ Freeway.

Family records indicate that the deed for one of his earliest purchases, 60 acres, was filed in Dallas County on Aug. 10, 1874.

Over time, he amassed nearly 2,000 acres in the area.

But Anderson Bonner met tragedy, too.

In the early 1900s, his wife, Eliza, was killed in a lamp explosion, which burned down their family home.

And while he came to own a large chunk of land, it was hard to keep it all. There were stories, Walter Bonner said, of people who agreed to buy parcels of his property but never paid him.

Anderson Bonner died in 1920, at the age of 86.

He left his land with his nine children and their families, and it was eventually split up or sold off over the years, long before it was known how lucrative North Dallas real estate would become.

Part of the land owned by Anderson Bonner became home to Medical City Dallas, one of the largest hospitals in North Texas.

The Bonner name remained intertwined in the history of North Dallas.

Black children in the area attended the Anderson Bonner School until 1955, when a new school in Hamilton Park opened. Walter Bonner and siblings went to Hamilton, where Walter graduated in 1961.

That following fall, the Hamilton Park football team won the state championship in the segregated Prairie View Interscholastic League.

The Wildcats' starting linebacker was Richard Bonner, Walter's little brother.

RELATED: 'We were taught to win': The legacy of an all-Black Dallas school's 1961 state championship

Both of the Bonner brothers spoke with WFAA last month about their time in Hamilton Park. They hoped their school's accomplishments would be remembered.

For Walter Bonner, he wants his great-grandfather's story to be remembered, too. And he hopes it can be an inspiration.

"If a man can not read or write his name can do this, think about what you can do," Walter Bonner said.

At the park, the city plans to dedicate a new piece of art in the coming weeks.

The piece, in honor of Anderson Bonner, will be placed along the trail, feet from the banks of the White Rock Creek, where he built a legacy that lasts today.

While the work remains under wraps, Walter Bonner said it will tell a story about coming from somewhere and "looking back."

And if his great-grandfather could be there, to see what his farmlands became?

"Oh I don't know," Walter Bonner said with a laugh. "He would probably just faint."