DALLAS — Richard Bonner sat in the bleachers at Hamilton Park last week. The same wooden bleachers that were there 60 years ago, when he was just a teenager, and he pointed to the homes across the street.

"When we went to play on Friday night, this was a ghost town," said Bonner.

And for good reason.

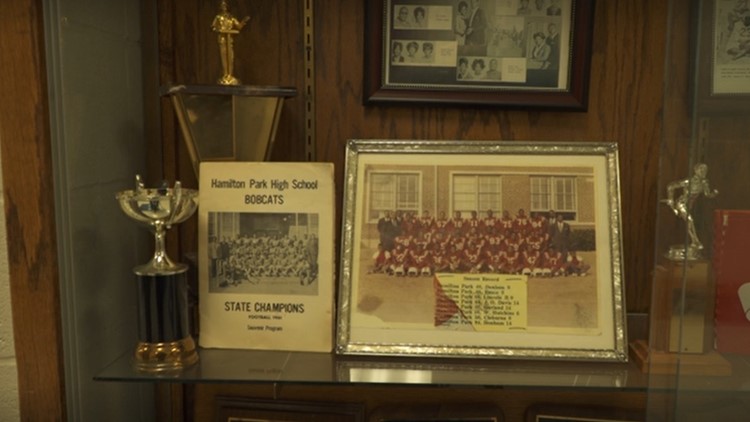

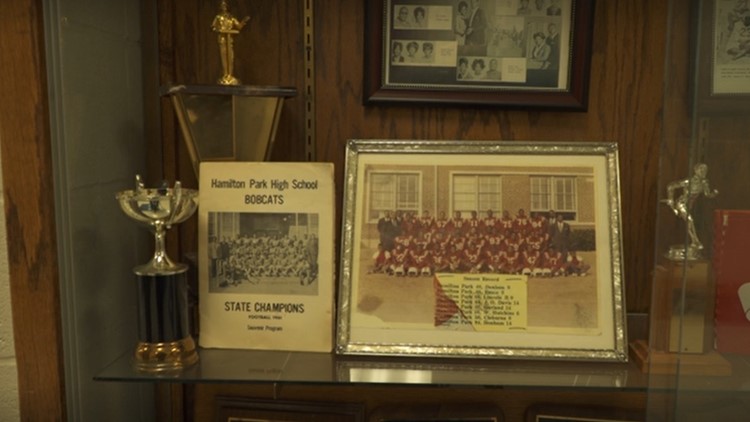

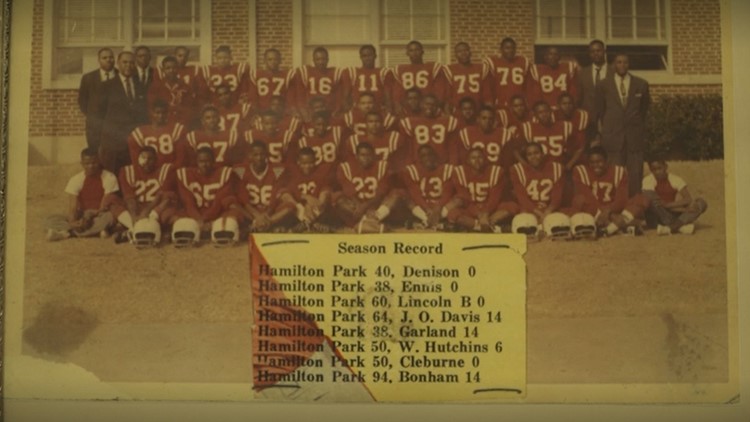

Bonner, now 76, was a sophomore linebacker on the Hamilton Park High School football team that won a state championship in 1961. Hamilton Park, in northeast Dallas, competed in the all-Black Prairie View Interscholastic League (PVIL).

The Bobcats and other teams in the PVIL weren't allowed to play against the all-white schools in Texas, at the time, though Bonner and his teammates would have liked a shot at Richardson High.

Still, all these years later, Hamilton Park, now an elementary school, remains in rarefied air.

Watch the full story from Jobin Panicker tonight on WFAA New at 10.

The Bobcats were the first team from the Richardson Independent School District to win a state football championship. And only one other, Lake Highlands in 1981, can lay claim to a title.

But the Bobcats' story was about more than football and record books. It was about a community, formed in the wake of discrimination and racial violence, and how it found a way to achieve greatness.

'Nobody can take what you know'

Dallas of the 1950s was two cities. One for white people. And one for everyone else.

Schools and restaurants and most other public settings were segregated, and for Black people, discrimination didn't stop at the doorway of their home.

Black homes in South Dallas were destroyed in a series of bombings, and a Black neighborhood in northwest Dallas was demolished to make room for Love Field's airport expansion.

Plans had already been in the works for a new subdivision of homes for Black families, and the result was Hamilton Park, a planned neighborhood on the outskirts of North Dallas.

Hamilton Park, today, sits on the southeast side of Interstate 635 and U.S. 75, one of the most bustling areas of North Texas.

But in 1954, when Hamilton Park opened, the surrounding area was still countryside. The neighborhood, which was named after the Black civic leader, Dr. Richard T. Hamilton, had a 12-grade school, and by 1961 there were 742 single-family homes constructed.

Black families came from across Dallas to live in Hamilton Park. Some, like Richard Bonner and his family, already lived in the area, where their great-grandfather, Anderson Bonner, came to own 2,000 acres of land after he was freed as a slave.

No matter where they came from, they found refuge in a small, but thriving, community in Hamilton Park.

"We were in a state of mind of achievements," said Barbara Callahan, a 1964 graduate of Hamilton Park High School. "We didn't care nothing about segregation. We didn't have that on our minds. It existed, but we had our own world here."

Callahan remembered when she was a girl and her family moved to Hamilton Park. On nice nights, they'd sleep in the backyard on cots.

"We called it a camping trip," Callahan said. "You didn't have any fears. You didn't have to lock your doors."

Carl Hanks, who grew up in Oak Cliff before his family moved to Hamilton Park, said the neighborhood took pride in their education. As his parents told him, "nobody can take what you know."

Hamilton Park students rarely cut class, Hanks and Callahan said, and no one stayed late at lunch.

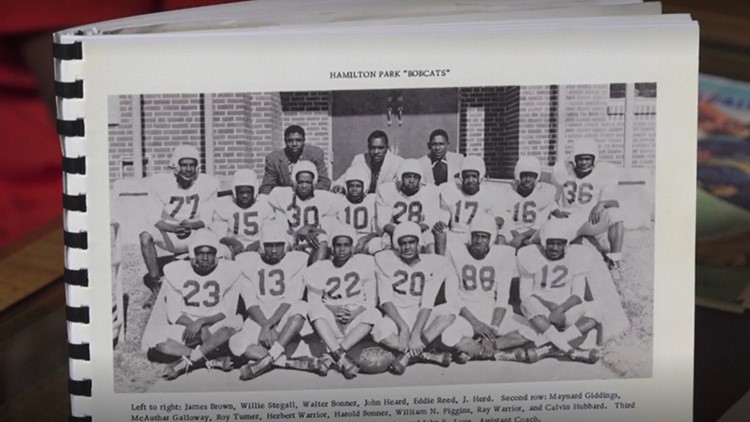

Photos: Memories of the 1961 Hamilton Park football team

As children in Hamilton Park, "we were taught to win," Callahan said.

And that showed up on the football field, as much as anywhere.

"We had a chance for a number of people who grew up in the Dallas area, played in the Richardson school district, who had the chance to come together and build our own unity," said Thomas Jefferson, a 1961 graduate who played on the football team. "And the unity consisted of: We wanted to win."

Jefferson and Walter Bonner -- Richard Bonner's older brother -- were seniors on the Hamilton Park team in 1960, the year before the Bobcats won state. And they'll quickly point out their team was better.

(Richard Bonner, for his part, will just as quickly point out that he was on that team, too, as a freshman.)

The 1960 team, led by Coach James O. Griffin, featured Jefferson, Walter Bonner and a future NFL Pro Bowler in Spider Lockhart, who played for the New York Giants. The Bobcats didn't get the attention that the all-white schools received, but that didn't matter.

"We knew about the other schools, and the white schools, but we were concerned with Hamilton Park," Walter Bonner said. "It wasn't about the other schools."

Bonner said Hamilton Park held opponents to less than 12 points per game, while averaging 30 of their own. But they were stopped short of a championship, losing in the state quarterfinals.

It turned out, 1961 was the Bobcats' year.

'We were all overachievers'

Richard Bonner still has his letter jacket, and it still fits.

Years ago, he rescued the red and brown coat from a fire, as his home in North Dallas burned down. The smoke darkened the red leather, but the Texas patch on the sleeve remains still clear: "State Champs '61."

"Why wouldn't you save a state championship jacket?" Bonner said. "Not everybody has one."

As the decades pass, Bonner's memories from Hamilton Park stay fresh in his mind.

He remembers the exact spot on the field where he got knocked out in practice. He remembers the bus rides to Sweeny, where they beat Carver High 24-0 in the state championship. He remembers how they pounded their helmets on the tin roof of the bus, the old "Yellowhound," as they called it. And he remembers the chant, too:

Water's in the pot, it's boiling hot. Can't be Hamilton with the stuff they got. Oh, Hamilton's red hot!

There aren't many Bobcats left from that 1961 team. Bonner is one of only a few surviving members. Leroy Brewster, the quarterback, passed away, and so did Bonner's best friend, John Alexander.

Bonner misses John and Leroy and all his friends from that team. He just hopes someone remembers what they accomplished.

"We were all overachievers," Bonner said. "We all just did everything we could to bring a lot of pride to this area, to our school, to our neighborhood. That was what we strived to do."