PASADENA, Calif. — The United States is set to host the World Cup for its second time in 2026 after welcoming the rest of the world in 1994.

Numerous storylines came from the 1994 World Cup:

- First World Cup final to be decided on penalties (Brazil defeated Italy 3-2 in penalty kicks after finishing the game 0-0).

- Brazil became the first nation to win four World Cup titles.

- Most financially-successful and highest-attended World Cup to date.

The list goes on and on.

And then, there was the murder of Colombian footballer Andrés Escobar.

Escobar was shot and killed outside a Medellin, Colombia nightclub days after he scored an own goal against the United States in a 2-1 loss during the group stage, which effectively eliminated the team from the tournament.

The entire saga is captured in ESPN's 30 for 30 documentary "The Two Escobars" (2010). The documentary tells the fascinating, tragic stories of drug kingpin Pablo Escobar and soccer player Andrés Escobar (no relation). Despite their lack of blood relation, the two were fatally connected, however, with a passion for soccer.

'Narco-soccer' takes control in Colombia

Colombian soccer league Categoría Primera A was mainly dominated by "The Millonarios", also known as Millonarios F.C., until the 1970s when Atletico Nacional, América de Cali and Deportivo Cali emerged as serious contenders.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Atletico Nacional and América de Cali took over the league and won championships, but were tied to prominent cartel leaders. América de Cali were tied to the Orejuela brothers from the Cali cartel, and Atletico Nacional was tied to Pablo Escobar.

The influx of "narco-soccer" money used to back these Colombian soccer teams allowed the clubs to retain their best talent, as well as bring in top players from around the world. Soccer in Colombia thrived, but it became an ego battle between drug lords who used these clubs essentially as their toys.

Escobar took it to another level, however.

After his favorite team, Atletico Nacional, lost a match against América de Cali in 1989, Escobar had the referee killed. The Colombian soccer federation immediately canceled the 1989 season thereafter.

Despite the Colombian soccer league canceling its season, Atletico Nacional went on to win the continental championship, Copa Libertadores, after beating Paraguayan side Olympia in penalty kicks.

The rise of club football in Colombia undoubtedly contributed to the national team's growth and success going into the 1990s.

Colombia enters 1994 World Cup as title favorites

The Colombian national team rose to prominence in the years leading up to the 1994 World Cup. Between 1991 and 1993, they won 25 of 26 matches, including a 5-0 beatdown of international soccer powerhouse, Argentina.

Brazilian soccer legend Pelé, highly-regarded as the best soccer player of all time, picked Colombia as his favorite to win the 1994 World Cup.

As favored as they were, however, the team was under a ton of pressure.

A little more than six months prior to the 1994 World Cup (December 1993), Pablo Escobar was killed by the Colombian military. Escobar's death unleashed a state of civil war, of sorts. ESPN's "The Two Escobars" explains that even though killings and violent crime were high under Pablo Escobar, it was channeled through him and his cartel. After his death, there was no order (or no Escobar) to keep low-end criminals in check.

Weeks before the tournament, Colombian midfielder Chonto Herrera’s son was kidnapped. Then, after Colombia were upset in the first group stage match against Romania, Chonto Herrera’s brother was killed in a car crash.

The team had also been receiving death threats. More than half of the Colombian national team were players who played for clubs financially backed by narco-traffickers (six Atlético Nacional, five América de Cali, one Millonarios), so many expect there was significant vested interest.

Talk about pressure. Oh, and the next match in the slate is against the World Cup host: the United States.

As if it were a nightmare, the match could not have started any worse for the Colombians. A cross from John Harkes was deflected by Andrés Escobar into his own net in the 34th minute. Seventeen minutes later, the U.S. tacked on another to make it 2-0. Colombia would lose 2-1 after scoring its lone goal in the 90th minute.

Losing two group matches in a row, Colombia had been effectively eliminated from the World Cup, and Andrés Escobar's own goal would end up being a fatal mistake.

After the game, Andrés Escobar wrote a column in a local newspaper, El Tiempo, calling for calm.

"Please, let's maintain respect," Andrés Escobar wrote. "A big hug for everyone, and let me say it was a phenomenal opportunity and experience, a rare one, which I've never felt before in my life."

In closing, Andrés Escobar said (chillingly ironic, in retrospect), "life doesn't end here."

The murder of Andrés Escobar

Andrés Escobar returned to Colombia days after the national team was eliminated from the World Cup. On July 1, 1994, he went to the El Poblado district of Medellin, ending up in a nightclub with three friends.

While he was at the club, Andrés Escobar was taunted by convicted drug traffickers Santiago and Pedro Gallon. The Gallon brothers reportedly shouted "goal" at Escobar.

Andrés Escobar asked the Gallon brothers to stop, was later separated from his friends and went back to his car at approximately 3 a.m. on July 2. The Gallon brothers and their bodyguard, Humberto Muñoz, were waiting for Andrés Escobar.

Another incident escalated between the Gallon brothers and Andrés Escobar, which led to Muñoz shooting the soccer star in the head six times. Muñoz reportedly shouted “goal” after every shot, echoing the six times the Colombian commentator repeated the word after the fateful own goal in the World Cup.

Muñoz was arrested and sentenced to 43 years in prison, which was later reduced to 26 years. He ended up serving less than 12 and was let out of prison in 2005.

After Andrés Escobar was killed outside that nightclub, his murder was met with outrage throughout the country and the world.

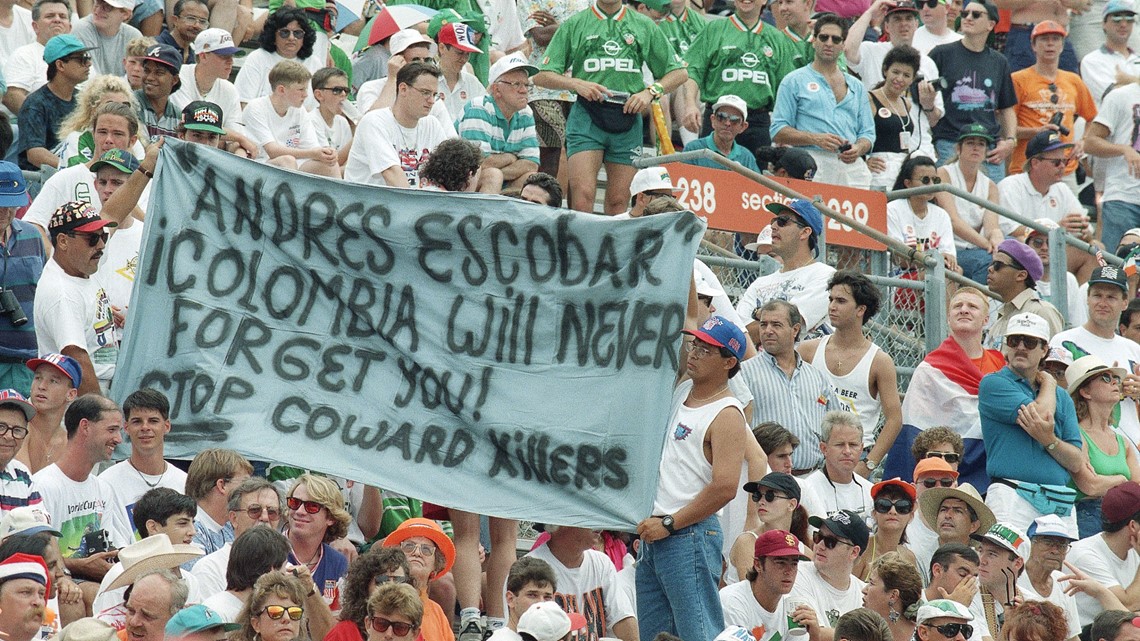

On July 4, 1994, fans at the World Cup match between Netherlands and Ireland held up a banner at Orlando's Citrus Bowl, which read, "Andres Escobar. ¡Colombia will never forget you! Stop coward killers"

It is estimated nearly 120,000 people attended Andrés Escobars' funeral on July 3, 1994. The anniversary of his death is still marked at matches in Colombia each year.

Colombian soccer regressed for decades. Colombia did qualify for the 1998 World Cup, but was again eliminated in the group stage round. They missed the next three World Cups. In 2011, the country fell to its worst FIFA ranking ever: 54th.

The tide turned for Colombia in the 2014 World Cup, however, when the team qualified for the first time in 16 years and made the country's deepest run at the title to date. The 2014 team swept the group stage and defeated Uruguay in the round of 16, 2-0.

But, like the 1994 World Cup, they were eliminated by the tournament hosts, this time being Brazil. Despite the elimination, the national team was greeted by tens of thousands of Colombians in Bogotá, welcoming them back as heroes and restoring pride to the nation.

It seemed like 1994's tragedy had served as a lesson learned ... until the 2018 World Cup.

Midfielder Carlos Sanchez received death threats following his team's loss against Japan at the 2018 FIFA World Cup, which prompted Colombian authorities to open an investigation. Sanchez received a red card just minutes into the match for a handball in the penalty area while trying to block a shot.

The death threats launched at Sanchez served as a chilling reminder of Andrés Escobar's murder. The threats led Escobar's brother, Santiago, to speak out.

“As a brother who has gone through this, I know what must be going through their [Sanchez’s family’s] heads, and I wouldn’t want anyone to go through that. Carlos must be feeling both sad for the mistake he made, and very afraid, and his family too. My brother never received any threats, they just shot him dead in the most cowardly way,” Santiago Escobar said. "The fact that people are still allowed to say these things on social network sites, even threaten him with death ... shows me that nothing good came out of Andrés’s death, nothing was learned.”

More World Cup coverage: