DALLAS — A Dallas-founded NFL team with oil-rich Dallas owners is heading to the Super Bowl again.

And yet again, it is not the Dallas Cowboys.

The Kansas City Chiefs punched their ticket to the Big Game for the fourth time in the last five seasons, beating the Baltimore Ravens in the AFC Championship Game on Sunday. This time, Kansas City will meet the San Francisco 49ers in a rematch of 2020's Super Bowl LIV, which the Chiefs won for their first of two titles. And if Kansas City manages to win again this year -- a third Super Bowl crown in five years -- the team will find itself among the great dynasties in NFL history.

All of which has to sting Cowboys fans just a little bit, considering this: The Chiefs' history in Dallas goes back just as far as the Cowboys, and even further.

The Chiefs were originally formed as the Dallas Texans as part of owner Lamar Hunt's upstart American Football League. Hunt, the son of oil tycoon H.L. Hunt, had tried to get an expansion NFL team in Dallas in the late 1950s, but the league declined. A previous iteration of the Dallas Texans went one-and-done in the NFL in 1952.

So Hunt decided to start a league and team of his own, the Texans, and planned to debut both in 1960.

By then, the NFL had responded to the rival league by giving Dallas businessman Clint Murchison Jr. that expansion team Hunt had wanted: The Cowboys.

Dallas, the city that couldn't get one team just a few years earlier, opened the 1960 football season with two: Hunt's Texans and Murchison's Cowboys, with both squads sharing the Cotton Bowl.

And the Texans were the immediate favorite, drawing more fans while winning more games than the Cowboys.

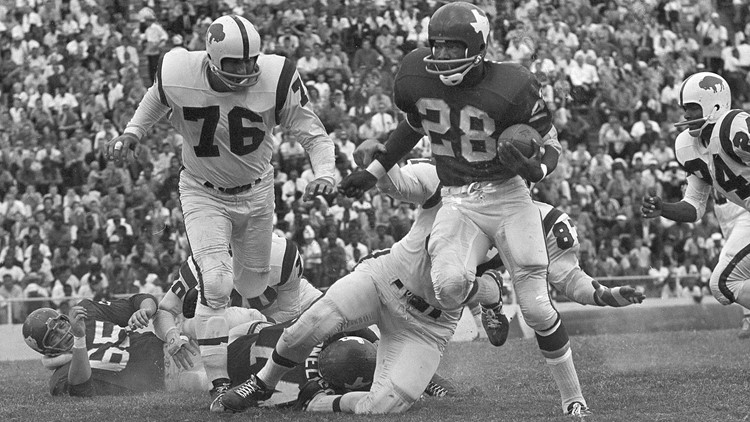

After going 14-14 their first two seasons, the Texans went on to win the 1962 AFL Championship, beating the Houston Oilers. The Cowboys, led by first-time head coach Tom Landry, went 9-28 in that span, including 0-11 in their debut season.

But Hunt saw the writing on the wall: Dallas was not a two-team town, and the Cowboys had an advantage with the NFL's backing.

The Associated Press reported that Hunt lost $1.25 million over his three-year money war with the Cowboys, despite selling more season tickets. Hunt's realization happened to coincide with two key developments, as NFL Throwback noted in this lookback piece in 2017: His AFL lawsuit against the NFL, accusing it of being a monopoly, was thrown out in 1962; and the NFL that same year agreed to a new television deal with CBS that would pay each team $300,000 per year.

If a pro football team was going to have success in Dallas, the Cowboys were in a far better position to do so.

Hunt explored Atlanta and Miami as possible relocation cities, according to the Chiefs' website. But as the AP reported, Hunt landed on Kansas City with a promise from Mayor H. Roe Bartle: The team would be able to sell 25,000 season tickets to their new fan base.

Hunt announced the move in February 1963, and the Texans headed north. Oddly enough, Hunt and coach Hank Stram considered keeping the Texans nickname, despite the Kansas City location. They ultimately decided to drop the moniker and fielded more than 1,000 different suggestions for a new one, according to the AP.

Hunt and Co. chose the Chiefs -- a tribute to Bartle's nickname, "Chief," according to the team website. What the nickname wasn't an homage to was Native American culture, despite the team using headdress imagery early in their stint in Kansas City.

The club said it later "worked to eliminate this offensive imagery," and they also started a dialogue with the American Indian Community Working Group in the Kansas City area.

Hunt's decision to exit Dallas proved to be a prescient one.

The Cowboys quickly became one of the more popular teams in football, with Landry building an all-time run of success into the 1980s. The Chiefs continued their winning ways at their new home, playing in Super Bowl I (a loss to the Packers), and winning Super Bowl IV over the Vikings.

Hunt's impact on pro football wasn't just that he established one diehard fanbase in Kansas City and cleared the way for another in Dallas. He also came up with the name "Super Bowl," a play on the popular Super Ball toy his children were playing with at the time.

Hunt's contributions to the early years of the AFL-NFL merger earned him induction to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1972. He died in 2006, but the team remains in the Hunt family today.

And the Hunts remain in Dallas.

The family never left town, only their team.