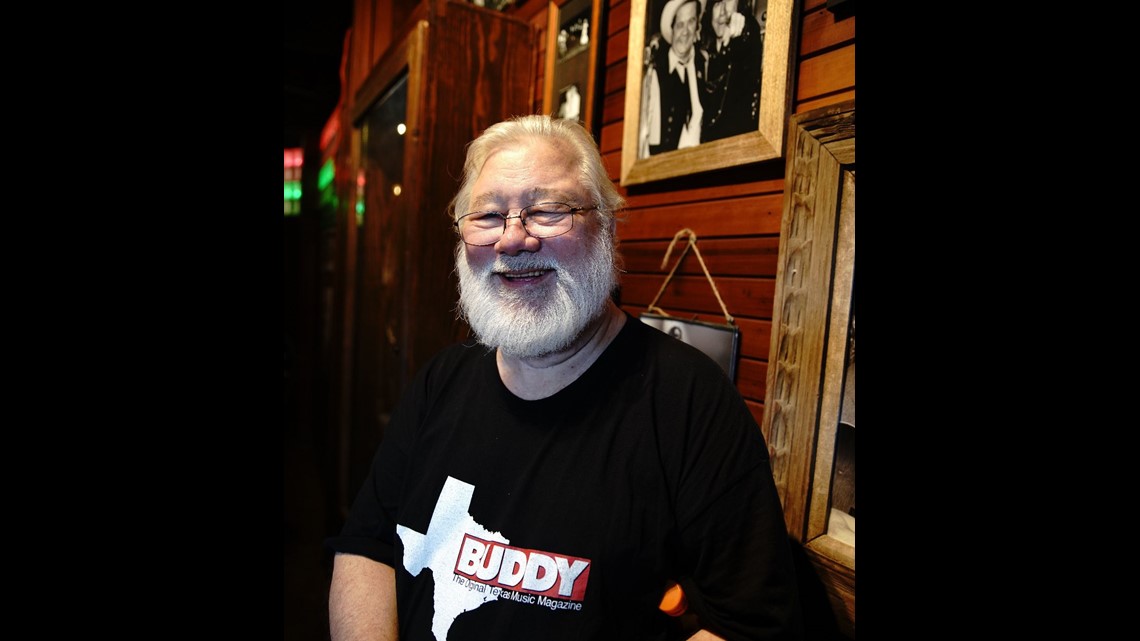

Buddy bills itself as “The Original Texas Music Magazine,” but in its early days the publication was as much a lifestyle as it was a job for the 10 souls who rolled it out every month.

“I would go to five bars in one night,” said Ron McKeown, one of the original staff members and now the editor.

As a staff photographer, McKeown’s job was to get photos of the talent, take in the performances and, if obliged, have a drink or two at each stop. After a bout with cancer decades ago, McKeown quit drinking.

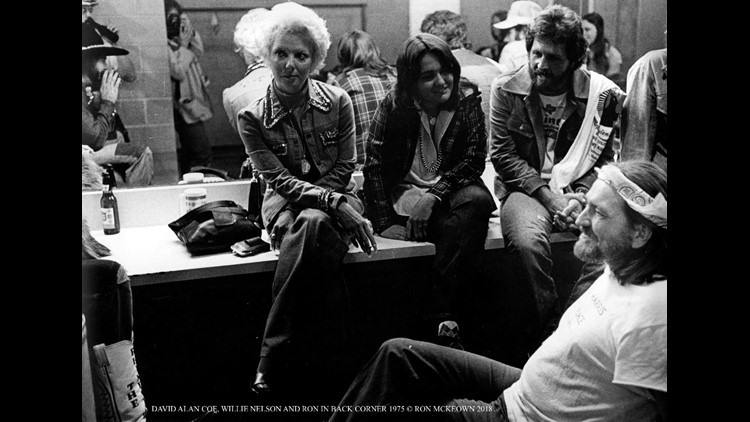

In the image with Willie Nelson above, McKeown can be spotted in the mirror at the back of the room, taking the photograph.

The magazine was the creation of Stoney Burns, whose original publication, the bi-weekly Dallas Notes, had an unwavering ability to get under the skin of the Dallas police.

Notes’ original title was Dallas Underground Notes, one of a wave of anti-establishment newspapers that flourished after the Vietnam war. Burns was arrested by Dallas police several times, and it was a marijuana possession charge that eventually got him a prison sentence of 10 years and one day.

Although the sentence was eventually commuted by Gov. Dolph Briscoe, the police confrontations were enough to convince Burns to produce a magazine about a less controversial counterculture: Texas music. A Buddy Holly caricature was on the magazine’s cover.

“There was no such thing as a music magazine,” McKeown said. “There was no Dallas Observer. There was no Guide in the Dallas Morning News. There was no place to learn about concerts and who was playing where. When we began writing, the musicians loved us and jumped right in to support us.”

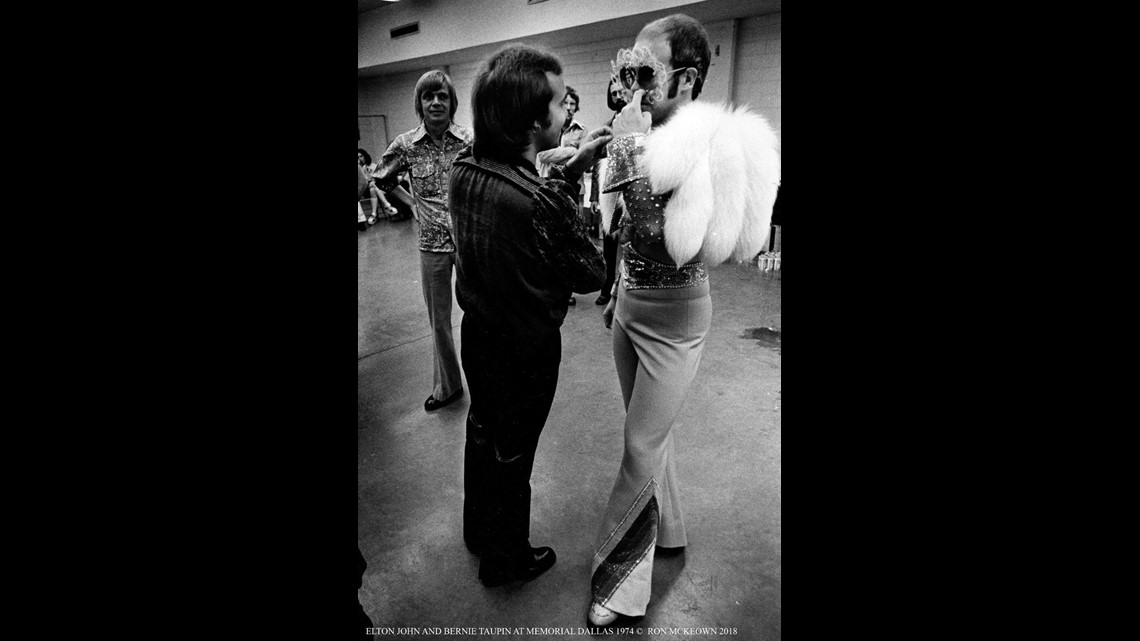

The big music studios—Columbia, Sony, and RCA among them—all had deep pockets and offices in Dallas to promote their artists. Buddy photographers spread out across the city.

“Sometimes I would see three different kinds of music in one night,” said photographer Jesus Carrillo.

Carrillo’s portfolio from those days includes images of Fats Domino, Jimmy Buffet, David Alan Coe, Joan Jet, Freddie King, Tina Turner and Steve Miller. McKeown’s portfolio is similarly star-studded.

Staffers were intoxicated by the scene.

“It was a trip,” said Steve Brooks. “We never knew what Stoney was going to do next.”

Printing tens of thousands of copies of Buddy each month, Burns, whose real name was Brent Stein, expanded sales to Austin and Houston.

“Not everybody liked Stoney,” McKeown said.

“He could be brutal,” said Dallas singer-songwriter Robert Lee Kobb. “If he didn’t like you, you didn’t get any ink.”

McKeown said the magazine flourished in the late '70s and early '80s.

“But Stoney didn’t like to pay people, and he decided to do everything himself,” McKeown said.

The magazine had engendered competition, and as Burns grew exhausted from staff reductions, circulation dropped.

McKeown took over as editor in the early '90s. Burns died in 2011.

Whatever prickly feelings some people might have harbored for Burns in life has since faded in the nostalgia for the time and the music, which is what was in the air at the 45th Buddy Magazine birthday party at the Longhorn Ballroom in August.

There were 10 hours of blues delivered by 11 bands. The audience skewed toward Willie’s age group rather than Jack White’s. There were canes and walkers in the audience, their owners bathing in the music as it washed over them.

Stacks of Buddy magazines used to go to record stores all over Texas. Today, there are few of those left, and newspapers of all ilks are fighting for survival.

McKeown now lovingly delivers a few thousand copies to clubs in North Texas.

“My last few years have been trying to keep the dream alive,” McKeown said

For a few true believers, he has.