Editor’s note: The following article contains sexually explicit references.

A dozen jurors walked into a Dallas courtroom two decades ago to deliver their verdict. For more than two months, they listened to graphic, horrifying testimony about a pedophile priest who preyed on young boys for years.

Witness after witness told their detailed stories of sexual abuse that stretched years by Rudy Kos, a long-time priest in the Roman Catholic Church. Even lawyers for the church and its bishop provided evidence against the priestly pervert in their own ranks.

Twenty years ago this month, the 12 Texas jurors issued a decision that rocked the very foundation of the church. They decreed that the church itself had sinned – that church leaders were grossly negligent because they knew about the sexual abuse but did nothing to stop it.

The jury ruled that the Catholic Diocese engaged in fraud and conspiracy to hide the crimes of Kos from the public, from law enforcement and even from parishioners. The jury awarded a historic and unprecedented $119.6 million to 10 young men who had been repeatedly molested as children by Kos. An 11th plaintiff had killed himself prior to trial.

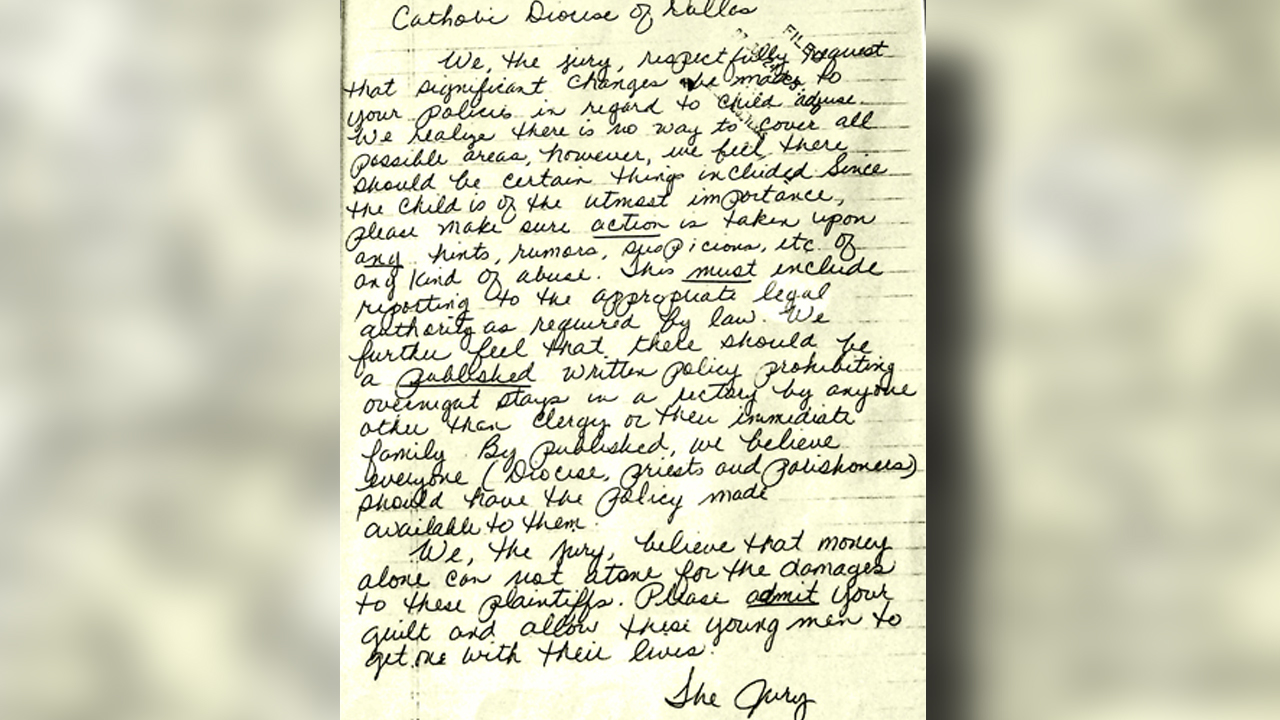

In an extraordinary move, the jurors wrote a letter to the diocese, which they read in open court after their verdict was rendered. The letter urged church leaders to change their policies on dealing with reports of child abuse.

RELATED: After the case, plaintiffs’ attorney represents more victims.

“Please admit your guilt,” the jurors said, “and allow these young men to get on with their lives.”

“We asked this jury to speak to the world, and they have done that,” Dallas lawyer Windle Turley said after the verdict.

Sylvia Demarest, another lawyer involved in the case, told reporters, “I hope they wake up the pope with this verdict.”

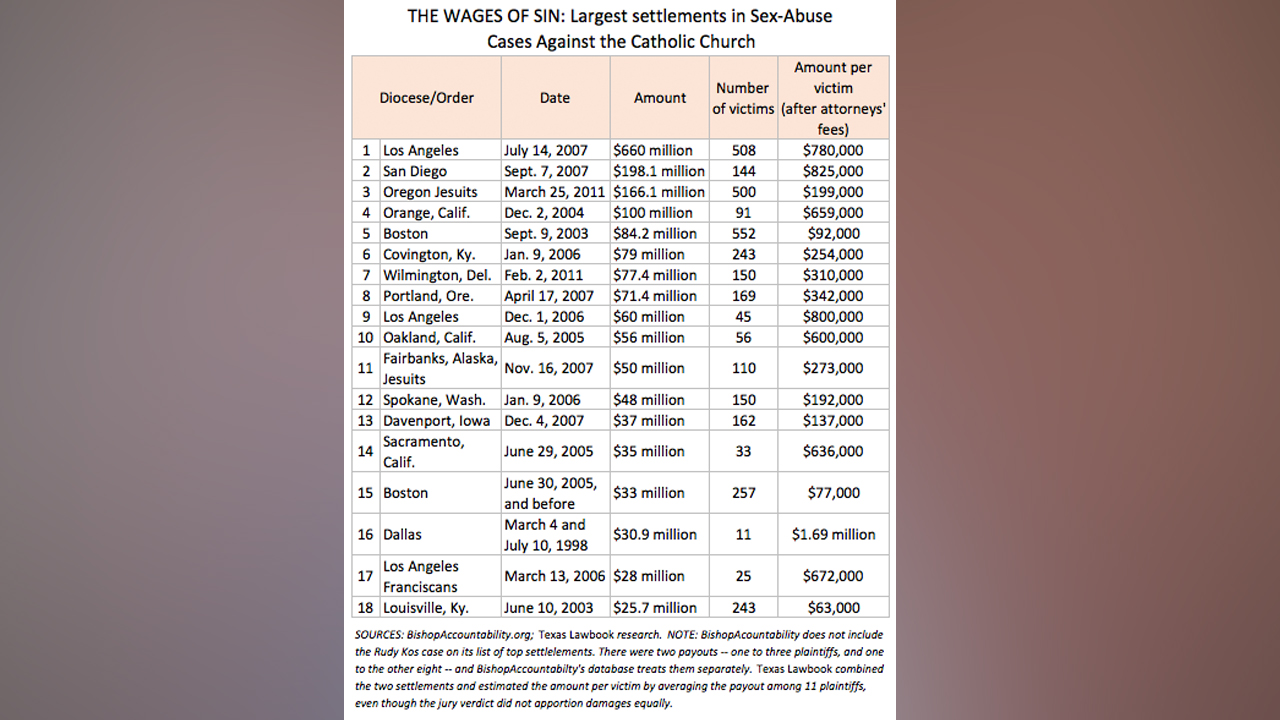

The diocese, claiming the jury’s judgment would plunge it into bankruptcy, settled with the plaintiffs for $30.9 million.

The trial itself, which the State Bar of Texas has called one of the most important cases in Texas history, was the first time that evidence of abuse by a Catholic priest and the church’s efforts to cover it up had ever been presented publicly in a U.S. courtroom.

The repercussions were far-reaching. Prosecutors used the testimony to bring criminal charges against Kos. The evidence unearthed in the Dallas trial was used and replicated in courtrooms across the country. The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops convened a special meeting in Dallas and enacted major reforms intended to ensure the safety of youngsters in Catholic parishes and parochial schools.

“Because the Kos case got so much attention – not only in the United States, but globally – it put the bishops’ conference in a position where it had to do something,” said Demarest, a lawyer representing the plaintiffs.

RELATED: From Rudy Kos comes a call: ‘Let’s talk after all.’

“The Kos verdict finally made it clear to the bishops that sexual abuse by the clergy could no longer be ignored,” Demarest said. “And it couldn’t be covered up. The clear message in the jury’s verdict was that the diocese had a moral and a legal duty to stop priests like Rudy Kos from preying on children.”

Legal experts say the Kos case essentially ended a decades-long practice by the Catholic Church of hiding the breadth of sexual abuse by priests and the complicity of the church’s hierarchy by hiding such allegations through secret settlements under court seal, which was central to the storyline in Spotlight, the Oscar-winning 2015 movie about The Boston Globe’s uncovering of a massive cover-up of sexual abuse by Catholic priests in the Archdiocese of Boston.

Turley said the church’s abandonment of secret settlements was a direct outgrowth of the Kos lawsuit.

“Until our case,” he said, “virtually all sex-abuse complaints against the Catholic Church resulted in settlements placed under seal by confidential agreement. Consequently, the public had no idea what was going on.

“We refused from the very start to negotiate a secret settlement. We said we wouldn’t do it. Secret settlements are bad for the public. They’re bad for society.”

While subsequent verdicts would later eclipse the jury damages award, the Kos case triggered an avalanche of similar claims against priests across the country.

Kos, by then stripped of his priestly duties, was living in San Diego and working occasionally as a paralegal. He never answered the lawsuit and never appeared in the courtroom of Judge Anne Ashby, who entered a default judgment against him.

That left the Diocese of Dallas as the sole target of the jury’s judgment, and its wrath.

“This case opened the door,” Turley said. “One result of the Kos verdict was a real empowerment of victims. It convinced them, as well as a substantial group of attorneys for victims, that they could make a difference.”

The Kos case shook the Catholic Church to its foundations. Randal Mathis, the attorney for the Dallas diocese, acknowledged as much in closing arguments.

“There's absolutely no doubt the diocese received your message very, very clearly,” he told jurors.

Mathis told The Texas Lawbook that he had “a great deal of respect for what the jury did, what it was charged with doing, and what it tried to do in this case.”

Demarest said that despite the settlements that made them millionaires, the plaintiffs in the Kos case weren’t all successful in their efforts to get on with their lives.

Today, one of her clients is a well-to-do entrepreneur who built and manages a diverse portfolio of successful business interests in the Dallas area. But another of her clients died this year in his mid-40s, losing what Demarest called a lifelong battle against the demons of drugs and alcohol. She’s convinced that his addictions were rooted in what Kos did to him.

The most recent annual audit completed by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops was released in May of this year. It found that survivors of child sex abuse had come forward with 1,318 new allegations against Catholic clergy between July 1, 2015, and June 30, 2016. That was more than in either of the previous two years.

Most of these new charges were “historical,” the audit said, meaning they were new revelations of old instances of abuse. But, disturbingly, “there were 25 allegations reported in this year’s audit involving current minors.” The message of that was not lost on the bishops.

While the church “has made great progress,” the audit said, “there is still work to be done.…”

For a longer version of this story, please visit TexasLawbook.net.

The Texas Lawbook, a content partner with the Dallas Business Journal, is a digital publication serving lawyers who represent businesses in litigation, transactional and regulatory matters in Texas.