DALLAS — Thousands of U.S. veterans who served at forward operating bases in Afghanistan and Iraq suffer rare cancers and unexplained illnesses from the military burning its trash. They say the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs has either delayed or denied their healthcare for too long.

“It’s a battle to get these cases approved and as time goes with delay and denial, veterans are dying,” said Le Roy Torres, Capt., U.S. Army, (Ret.) who was deployed in 2007 and 2008 as a logistics officer in Balad, Iraq.

At bases in both battlefields, the U.S. military would pile its waste in one area and set it ablaze using either diesel or jet fuel. They’re called burn pits.

The fires incinerated not only daily trash like paper, but also plastics, tires, batteries, broken rifles, unspent ammunition and old engine parts.

The heavy black smoke would waft across the base, and troops often had no choice but to inhale it.

“Where I was at in Balad, [the burn pit] was approximately 10 acres in diameter,” Torres, 46, said.

Dr. Daniel Brewer, the military’s chief environmental engineer for Afghanistan and Iraq, said he also saw asbestos, hazardous waste, medical waste and more being incinerated in these open landfills.

All of it created black smoke containing carcinogens and vaporized metals, Brewer said.

“This didn’t look like a good practice, and I told them so,” he said. “A lot of times they’d burn the really bad stuff at night. The problem is people are sleeping at night in the tents and stuff and they’re just breathing these fumes all night long and don’t even know it.”

Torres was recently diagnosed with toxic brain injury.

"I have been suffering from these headaches for a couple years now – almost a decade of headaches, memory issues, concentration issues,” he said.

In 2013, the V.A. was mandated to create a Burn Pit registry – a list of all veterans who now suffer adverse health effects from the military fires.

So far, there are 175,375 veterans and service members names on the registry.

But six years after that data collection began, Torres and other vets say it is time for the V.A. to finally act.

“Data has been collected but that’s all its been doing, just collecting data. Hasn’t created any specialized healthcare. Haven’t done anything for those of us who are suffering from these invisible wounds,” Torres said. “They recognize Traumatic Brain Injury but at this time Toxic Brain Injury is not even something that’s being looked at.”

He returned to Texas with excruciating headaches and shortness of breath. He first recognized his symptoms soon after returning to his job as a state trooper.

“I couldn’t catch my breath after the foot pursuit. I was able to get the guy in custody but afterwards I thought I was having a stroke. I was having shortness of breath,” Torres recalled.

His lungs were losing their elasticity and he would have a harder time breathing as he ages.

It spurred Torres to start Burn Pits 360, a non-profit that maintains its own registry of veterans like him.

“On our registry alone, there’s over 120 that we know of who have died from exposure issues,” he said.

Hundreds of younger vets – in their 20s and 30s – have developed rare cancers and unexplained illnesses.

“I just feel like my life has been taken from me and I'm not being able to live the life I thought I was going to live,” said Nicole Rosga, 33.

She shares some of Torres’ symptoms after serving in Iraq as a member of the Air National Guard. Rosga, now attached to the 125th Fighter Wing in Jacksonville, Fla., just deployed again.

She said she was often instructed to take classified material to the edge of the burn pit and wait until flames fully consumed it.

“This is a real thing. This is real. And it might be worse than Gulf War [Syndrome]. It might be worse than [Vietnam-era] Agent Orange. But they need to step up,” Rosga added.

And that’s the problem.

Veterans are either dying or facing exorbitant medical bills and have begun to grow frustrated that the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs considers these claims on a case-by-case basis instead of just treating the health effects from the toxic smoke.

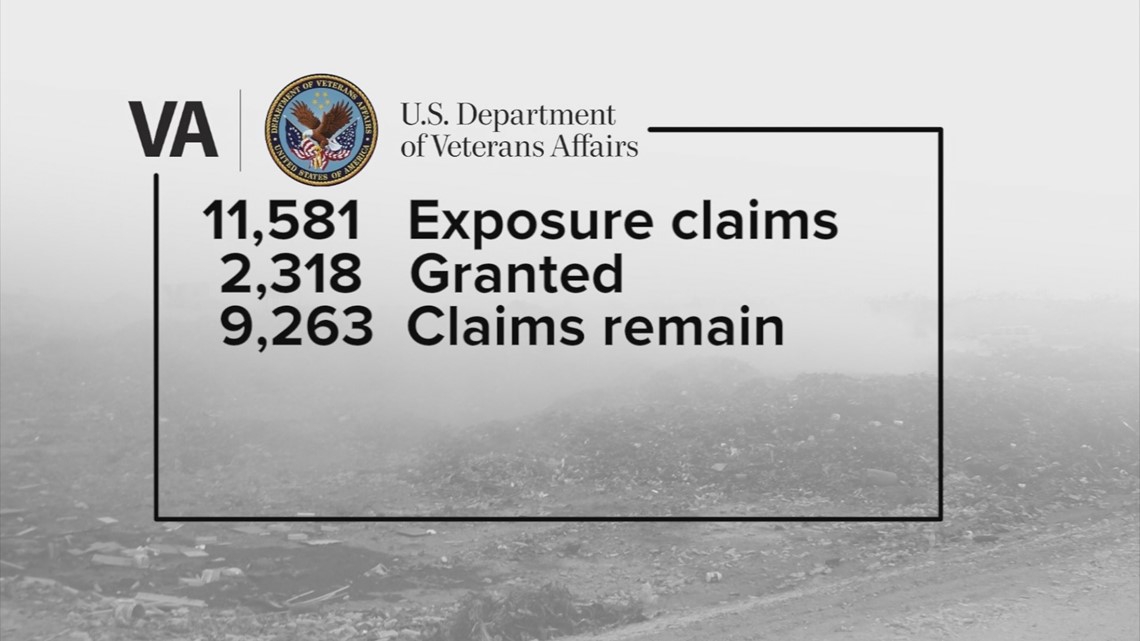

Over the last decade, the V.A. said it got 11,581 burn pit claims from vets but it only granted care in 2,318 of the cases, which leaves thousands of veterans responsible for their own treatment.

In a statement, the V.A. downplays burn pit exposure, saying it makes up less than one percent of all claims.

“V.A. looks continually at medical research and follows trends related to medical conditions affecting veterans,” the statement said. “There are multiple ongoing and extensive DoD and VA studies looking at airborne hazards exposures. V.A. is in process of contracting with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine to provide another comprehensive review of respiratory health effects of airborne hazards in Southwest Asia. The Academies’ report is expected in mid-2020.”

Torres and other vets recently got the attention of U.S. Rep. Joaquin Castro, who says money is likely a factor in the V.A.’s decision to not treat every vet who says inhaling toxic smoke harmed them.

“I’m sure that’s part of it. I’m sure there’s somebody running the numbers and saying, 'Hey, how much is this going to cost us,’” the San Antonio Democrat said.

He introduced two bills, H.R. 1001 and H.R. 1005, which, among other things, would force the V.A. to finally do something with all its data and recognize Torres’ condition. On Tuesday, April 30, Castro along with U.S. Rep. Raul Ruiz, D-Calif. and Sen. Tom Udall, D-New Mexico, held a briefing in Washington, D.C. to try and create more support for his legislation and the issue at-large.

“We need to take all that information that we got on our Burn Pit registry, figure out the most common ailments and what exactly happened to their bodies,” Castro said, “and then I think do something more to compensate their families and the service members. The boulder we’re trying to push up the hill is trying to get the government to acknowledge that there was something wrong in what happened. Unfortunately, we have seen over the years that can sometimes be a tough thing to do.”

In Austin, Torres is working at the state legislature asking lawmakers to create a new registry of Texas veterans who have been exposed to toxic smoke from burn pits. House Bill 306, which would create the list, has already passed both chambers and now heads to the governor’s desk for a signature.

For now, Torres is responsible for his own treatment at Hyperbaric Centers of Texas in Dallas.

He meets regularly with Dr. Al Johnson, hoping pure oxygen will help his lungs regain their elasticity.

“The hyperbaric [chamber] takes cells that have been scarred, cells that have been injured, helps decrease the scarring,” Johnson said. “Hyperbaric oxygen is 100-percent oxygen in a chamber, under pressure which fully saturates the blood vessel.”

Other vets facing similar exposure issues have also had treatment in hyperbaric chambers, Johnson said.

Headaches have eased, and so far, Torres added, hyperbaric treatment is better than any drug doctors have prescribed.

“The doctors have told me its irreversible. I still, I keep the faith,” Torres continued. “I’m going to beat this. I’m going to beat this.”

Brewer said burn pits aren’t necessarily bad — the military was not segregating the waste.

The 10-acre burn pit in Balad, Iraq was replaced with an incinerator containing a stack to send the smoke higher in the air and away from the life on the ground.

Despite his prognosis, Torres said he has no hard feelings against the military.

“I don’t feel betrayed. I believe it’s just an issue that hasn’t been continuously addressed. That there has to be pressure for a change,” he said. “I believe that many of us have been forgotten.”

But the battle against the V.A. is one fight Torres and many of his fellow vets did not expect.