As midnight nears, the lights of El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, fill the sky on the silent banks of the Rio Grande. A few months ago, hundreds of asylum-seeking families, including crying toddlers, waited for an opening to crawl through razor wire from Juarez into El Paso.

No one is waiting there now.

Nearly 500 miles away, in the border city of Eagle Pass, large groups of migrants that were once commonplace are rarely seen on the riverbanks these days.

In McAllen, at the other end of the Texas border, two Border Patrol agents scan fields for five hours without encountering a single migrant.

It’s a return to relative calm after an unprecedented surge of immigrants through the southern border in recent years. But no one would know that listening to Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump talking about border enforcement at dueling presidential campaign events. And no one would know from the rate at which Texas is spending on a border crackdown called Operation Lone Star — $11 billion since 2021.

Trump, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott and other elected officials often refer to the country’s “open border” with Mexico. Immigration is a top election issue in the presidential election, and most American voters say it should be reduced.

But conditions on the border often shift more rapidly than political rhetoric. Arrests for illegal crossings plummeted nearly 80% from December to July. Summer heat typically reduces migration, but on top of that Mexican authorities sharply increased enforcement within their borders in December. Plus, President Joe Biden introduced major asylum restrictions in June.

Crossings are still high by historical standards and record numbers of forcibly displaced people worldwide — more than 117 million at the end of last year, according to the U.N. refugee agency — may make the drop temporary. And some Republican critics say Biden’s new and expanded legal pathways to enter the U.S. are “a shell game” to reduce illegal crossings — along with the chaotic images and headlines they spawn — while still allowing people in.

The Associated Press and The Texas Tribune spent 24 hours in five cities on Texas’ 1,254-mile border with Mexico to compare rhetoric with reality.

On the riverbanks of Ciudad Juárez, there are no migrants in sight, but evidence of previous crossings still litters the ground. Discarded clothes entangled in razor wire. A toothbrush and a Mexico City train-bus pass littering the riverbed.

A van from Mexico’s immigration agency is parked nearby, the driver keeping an eye on the river. It is a reminder of intensified Mexican enforcement that followed a plea for help by senior U.S. officials in late December.

On the opposite bank in El Paso, Texas National Guard members in unmarked pickup trucks and Texas Department of Public Safety troopers are watching the river too. “You can’t be in this area,” a rifle-toting American soldier shouts in Spanish to journalists across the river.

In the preceding week, the Border Patrol was processing and releasing an average of fewer than 200 migrants a day in El Paso, down from a daily average of nearly 1,000 in December and nearly 1,500 in December 2022. Migrants are no longer sleeping overnight in large numbers on downtown streets, once a common occurrence.

At El Paso International Airport, a shuttle van unloads dozens of migrants at 3:30 a.m. The terminal is quiet but, not long ago, hundreds of migrants slept there nightly, including many who missed their flights because it was their first time flying, and short-staffed airlines were unprepared to answer their questions.

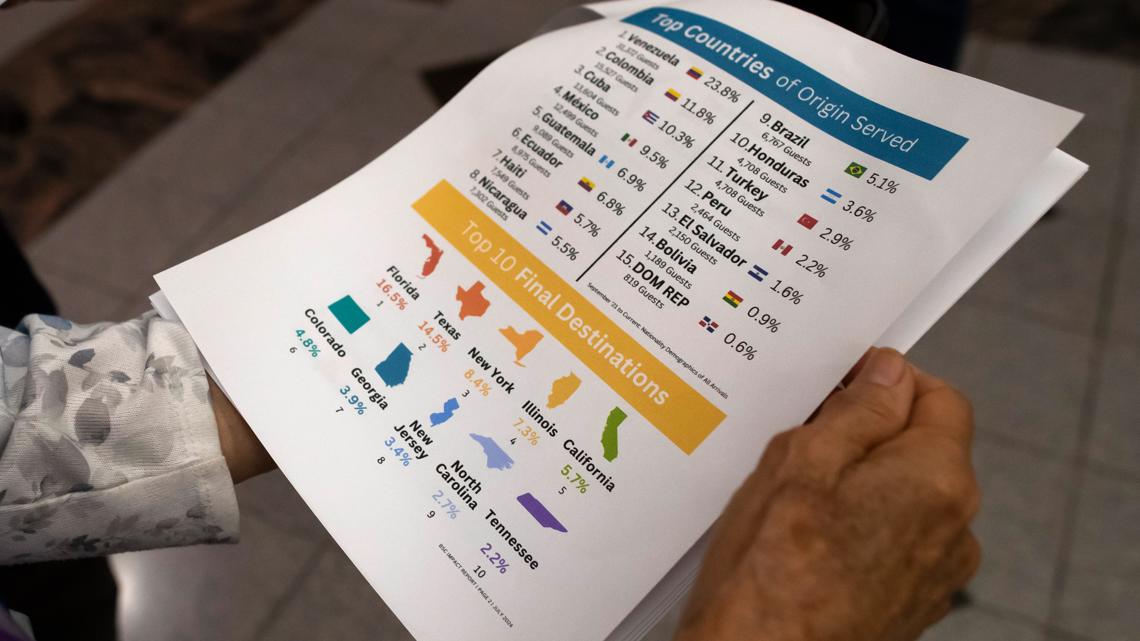

Border Servant Corps, a nonprofit group from nearby Las Cruces, New Mexico, says it has helped more than 130,000 migrants with more than $18 million in shelter and travel support to their final destinations in the U.S. Nearly one of four migrants are from Venezuela, followed by Colombia and Cuba. The leading destinations are cities in Florida, Texas, New York and Illinois.

Ceci Herrera, a retired social worker and Border Servant Corps staffer who helps migrant families navigate the airport, says she knows what it’s like to lack a sense of belonging.

“In immigration, it’s important to say you belong to a country instead of feeling like you’re neither from there nor over there,” she says at the airport after helping migrant families get their boarding passes.

Many migrants are released with notices to appear in immigration court, where they can request asylum. They can apply for work permits in six months while their cases take years to decide in bottlenecked courts.

Additionally, more than 765,000 have legally entered from January 2023 to July through an online appointment system called CBP One, which allows them to stay for two years with work authorization. The federal government offers 1,450 appointments a day across the southern border, including about 400 in Brownsville, about 200 each in El Paso and Hidalgo, near McAllen, and smaller numbers in Eagle Pass and Laredo.

At the airport, 39-year-old Yenny Leyva Bornot, who fled Cuba with her husband and their 14-year-old son, was still absorbing the fact that they had gotten one of the treasured appointments and made it to the U.S. “We are in a country of freedom,” she said.

The family flew to Nicaragua in November then traveled over land to Mexico, the only country from which migrants can apply online for appointments. They got one in El Paso after seven months of trying, relying on an uncle in Germany, an aunt in Spain and a brother-in-law in Sarasota, Florida, to help cover their expenses.

Now their flight to Florida is delayed.

“What’s two more hours after seven months?” Leyva Bornot said. “This is the dream for most Cubans: Come to the United States to work and help your family back home.”

Hundreds of miles away near McAllen, Border Patrol agents Christina Smallwood and Andrés García leave their station two hours before sunrise. They drive along a levee road near where a towering border wall built during the Trump administration is lit up like a baseball stadium. After years of wall building, the Texas-Mexico border still has only about 175 miles of barriers, covering less than 15% of its length.

The agents peer through overgrown stands of carrizo, searching for makeshift rafts and ladders that are abandoned there by people who make it across the river.

The area near the Hidalgo bridge is a known hotspot for border crossers seeking to elude capture, as opposed to the asylum-seekers who quickly surrender to agents, because it is near a heavily-traveled road. They can easily hop into a car and get lost in the traffic.

It’s quiet now. The agents don’t see a single migrant in nearly five hours.

“Compared with numbers over the last decade, it’s insane the difference right now,” Garcia said.

Roughly 150 miles upriver in Laredo, the sound of rumbling motors from tractor-trailers and the smell of diesel and exhaust fill the warm air as vehicles line up on the World Trade Bridge — one of four international bridges in the city.

“It starts getting busy for us, 10 o’clock, 10 or 11. And it’ll be pretty constant up until about four or five in the afternoon,” said Alberto Flores, director of the Laredo port of entry.

On the Mexican side of the border, what appear to be tiny white boxes stretch toward the horizon. They are tractor-trailers, filled with goods from warehouses in Nuevo Laredo.

Laredo is by far the busiest entry point for cargo in the United States, funneling more than twice as many tractor-trailers as second-place Detroit over the last year.

About 8,000 tractor-trailers filled with goods from flowers to lettuce to car parts pass each day through 19 lanes at World Trade Bridge, northwest of downtown Laredo. It is a straight shot on Interstate 35 to San Antonio and Dallas.

At a booth for prescreened truckers, a Customs and Border Protection officer opens a sliding window and takes a sheet of paper from the driver. The computer brings up a manifest that says the truck carries 20 pallets of a solution used for dialysis.

“We’re verifying everything is basically accurate. And if it’s accurate and there’s no anomalies, anything in the system, then he’s good to go,” the officer says.

The next vehicle is a tractor-trailer cab, likely going to pick up an empty container on the U.S. side and bring it back to Mexico. The officer tries to limit each inspection to 45 seconds.

Flores wants to “make sure that cargo is constantly flowing” – a challenge when illegal crossings are unusually high. In December, cargo crossings temporarily closed in Eagle Pass and El Paso – as well as a crossing in Lukeville, Arizona – as officers were diverted from ports of entry to deal with the surge in migrants arriving at the border. Local businesses said the closures sent business plummeting, and a related five-day closure of two border rail crossings cost industries $200 million per day, according to Union Pacific.

Flores visits a small mobile home inside the bridge’s inspection area to congratulate an employee who searches images on a large X-ray machine known as a Multi-Energy Portal. The officer was inspecting a shipment of flowers when he spotted something unusual. It turned out to be more than 700 pounds of methamphetamine.

The rectangular machine produces detailed, black-and-white scans of tractor-trailers and their cargo that look like charcoal drawings. CBP will have four more such machines by October for use on most commercial traffic.

“Can I have the day off?” the officer asks Flores. The room full of CBP officers erupts in laughter.

“I’ll get back to you,” Flores says.

The recent decrease in migrant apprehensions has not slowed the flow of drugs across the border. Mexican cartels are at the heart of what the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration calls a crisis of deadly synthetic drugs, with chemicals originating in China being mixed in Mexico and taken across the U.S. border, often by U.S. citizens. Federal statistics show that 46% of drug seizures nationally happened at the U.S.-Mexico border in the 2021-23 fiscal years.

The largest seizures of fentanyl, heroin, methamphetamine and cocaine occur at border crossings in Arizona and California, but Flores says methamphetamine and cocaine often come through Laredo. The DEA says a faction of the Sinaloa cartel called “Los Chapitos” favors an El Paso crossing for smuggling narcotics.

The methamphetamine is examined with a small handheld device inside a refrigerated storage facility with loading docks. There were no arrests in the incident, which is under investigation, but the drugs were confiscated, a CBP spokesperson said.

Other trucks called aside for closer inspection include one filled with plastic cups for the popular Texas-based fast food chain Whataburger and another with cans of tuna. A K-9 German Shepherd named Magi inspects one filled with marble tile.

Laredo’s other international bridges funnel visitors, students and commuters in cars and on foot, a lifeblood of the local economy here and in other border cities. But Laredo stands out because it has no border wall, a result of opposition from private landowners. And cartel-related violence in Nuevo Laredo has long made it unattractive for migrants to cross.

Monica Ochoa, who waited with her 5-year-old daughter at the historic San Agustin Plaza for her mother to pick them up, says her living arrangements are “very complicated,” working as a schoolteacher in Mexico while her daughters, both U.S. citizens, attend school in Laredo. Though she says media depictions of Mexican violence are often overblown, she said safety was one reason she wants her children to live in the U.S.

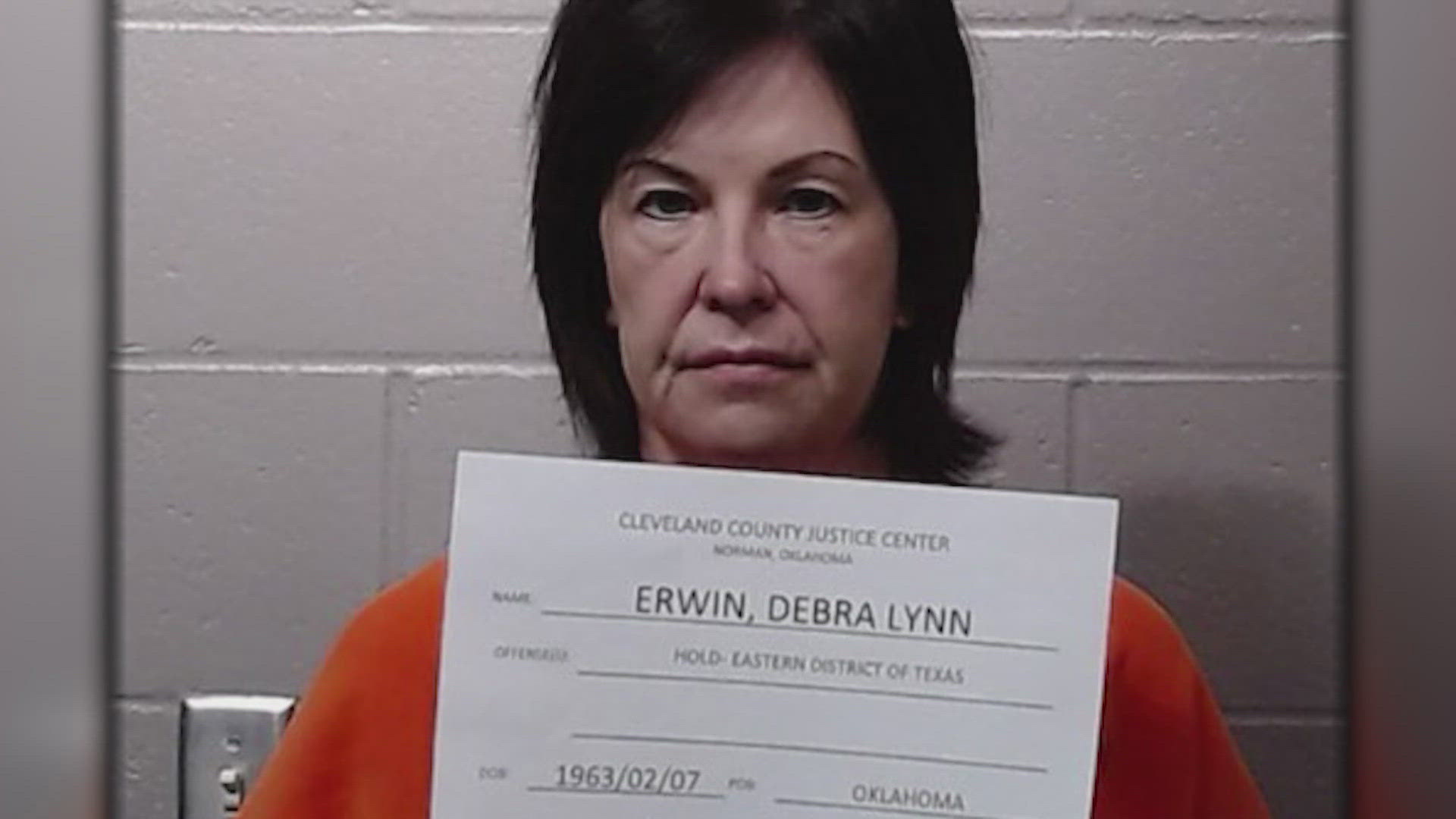

Webb County Judge Leticia L. Martinez is wrapping up a morning session that started on Zoom with 49 tiny screens. Migrants and their lawyers filled the virtual courtroom as Martinez runs through criminal charges filed against the migrants under Operation Lone Star. The state announced that day that it has made more than 45,000 arrests since the crackdown began in 2021 and filed nearly 40,000 felony charges, often for trespassing on private property.

Some defendants dial in from Latin America with spotty connections that interrupt exchanges, showing up for court even though they have already left the country. Some who have been deported are no-shows, their lawyers saying they couldn’t be found. Those who show up are often confused.

One man is lying down as Martinez starts calling names. Another stands in front of lush green trees.

A court interpreter asks one man to remove his baseball cap when his case is called. The man turns the cap backwards, complying only after the interpreter impatiently repeats the command in a raised voice.

As the judge plows through the list, she dismisses the case of another migrant after a prosecutor acknowledges the state has no evidence to charge him.

“Muchas gracias,” a voice says on the other end with a camera just showing the back of a van.

The judge tells two men who appear on camera in orange jumpsuits from a prison in Edinburg that they will be turned over to federal authorities for deportation. One pleads for an urgent transfer, claiming he’s been threatened by violent jail gangs.

“I’m scared,” he says, to no avail. “I want to make it to Mexico to see my kids, my grandkids. They’re little.”

He went on, “I don’t know how to read. I don’t know how to write. I just came not knowing what would happen. Please forgive me. I will never again…”

The judge tells the man that he’ll likely be removed from the jail and turned over to the federal government the next day.

Before adjourning, the judge hears from the attorney of a man who has apparently been kidnapped. Prosecutor Steven Todd says the case should not be continued because the man is a no-show, but Martinez disagrees.

“Well, he’s not absconded. He was kidnapped. Very big difference,” the judge says.

At an El Paso church kitchen, a woman cooks beef with red chile, beans and rice while a 22-year-old Guatemalan man in a wheelchair sets tables. The man said he experienced brain injury from smoke inhalation in a fire last year at a immigrant detention center in Ciudad Juárez that killed 40 people, impairing his ability to walk and talk.

The church is part of a network of migrant shelters called Annunciation House, a group founded in 1978 by Ruben García, a well-known local Catholic humanitarian who has worked with federal immigration officials to house recently arrived migrants. A state judge recently dismissed a lawsuit against Annunciation House by Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, who accused the group of illegally sheltering migrants and refusing to turn over records. Despite the outcome, the charges sent shockwaves throughout the community of migrant advocates along the border. Using similar allegations, Paxton has pursued others, including Catholic Charities of Rio Grande Valley.

Early that morning, García received his daily text message from a Border Patrol agent: The agency would release 25 people in El Paso that day. García said he could take them.

It is the lowest daily number García has seen in four years. The most the Border Patrol has sent to the shelters was 1,100 in a single day; earlier this year García said they took in 600 one day.

“This February, I will have been doing this for 47 years,” he said, sitting on a chair in the church. “My experience tells me this never lasts.”

The attorney general’s office said in court documents that Annunciation House appears “to be engaged in the business of human smuggling,” operating an “illegal stash house” and encouraging immigrants to enter the country illegally because it provides legal orientation. The state sought logs of clients’ names, a grant application the shelter has filed with the federal government, materials it has provided to migrants, and a list of all the shelters Garcia operates.

Paxton’s office has appealed the case to the Texas Supreme Court. Garcia says some volunteers have decided not to help out of concern they could be prosecuted.

“I would hope that instead, it would galvanize people to say, ‘I’m not going to look the other way. I’m going to go and offer myself to work with refugees and to be part of the process of providing what is imminently a humanitarian response,’” he said.

Shelby Park in Eagle Pass is ground zero for Operation Lone Star, Texas’ unprecedented challenge to the long-standing principle that immigration policy is the federal government’s sole domain. Texas argues that it has a constitutional right to defend against an “invasion” and that the migrant influx has been a drain on public coffers.

Under Lone Star, Texas has bused about 120,000 migrants to cities including New York, Chicago and Denver. State troopers and the Texas National Guard have become a massive presence in towns on the state’s border with Mexico, which is about two-thirds the length of the U.S.-Mexico border.

Andrew Mahaleris, a spokesperson for Abbott, defended the governor’s immigration enforcement efforts — including transporting migrants to other cities — and claimed that illegal crossings have recently dropped because of Operation Lone Star.

Maheleris said in a statement that until Biden and Harris “step up and do their jobs to secure the border, Texas will continue utilizing every tool and strategy to respond to the Biden-Harris border crisis.”

The state has put razor wire in many areas, including a triple-layer barrier in Eagle Pass. The state installed a floating barrier made of buoys and submerged netting near Shelby Park to deter river crossings.

The park, a flat expanse of playing fields and a boat ramp at the end of the downtown business district and next to a golf course, has been closed since Texas seized it from the city in January and made it into a riverfront staging area. U.S. Border Patrol agents are denied entry. Texas authorities did not respond to requests to enter the park on this day.

Eagle Pass, a town of 30,000 people filled with warehouses and aging houses, was for much of 2022 the busiest of the Border Patrol’s nine sectors on the Mexican border. Daily arrests for illegal border crossings in the sector averaged 255 in June, down from nearly 2,300 six months earlier.

Shelby Park, once a place where local kids played soccer and the city hosted big events — and more recently a spot where large groups of migrants crossed the border almost daily — is now a dusty makeshift military base. Armed soldiers walk atop shipping containers and stand guard at its entrance with long guns.

Across the street from the park, George Rodriguez, a 72-year-old Eagle Pass native, prepares to beat the afternoon heat and close his stand at a flea market, where he sells pink typing keyboards, a vacuum cleaner and a television mount. He says blocking Border Patrol from part of the border is senseless.

“Once in a while, the governor and his cronies come over here and make a big deal,” Rodriguez said over music crackling on the radio, furniture scraping pavement and clothes hangers pattering in the wind. “It’s just a political stunt.”

Roughly a mile up the Rio Grande, two workers at the city water treatment plant come across a bag filled with socks. There are no fresh footprints on the sand road. A few months ago, they would have found piles of clothing and garbage that could gum up the pumps.

Stories of why migrants come have changed little in recent years, often a mix of wanting to improve their lives economically and fear of violence in their home countries. What has changed is the numbers – and perhaps nowhere more than in Rio Grande Valley.

The Border Patrol’s Rio Grande Valley sector, the nation’s busiest from 2013 to 2022, saw arrests plunge to an average of 133 a day in June from more than 2,600 in July 2021. Many are released with orders to appear in immigration court, where a backlog of 3.7 million cases means it takes several years to decide asylum claims.

In Brownsville, Jose Castro Lopez, 32, sat inside the main bus station more than four hours before an 8 p.m. ride to Florida. His partner and their children arrived following a two-month journey from Honduras that took him to Mexico City, where he applied for entry on the CBP One app.

He said construction work in Honduras didn’t pay enough to support a family.

“I’m sleep deprived and stressed,” he said. “But, thank God, we’re fine now. God allowed us the privilege to be here.”

Another passenger at the bus station, Lilibeth Garcia, 32, said she graduated in 2016 from medical school in Venezuela, where she studied to be a surgeon, but the country’s economic tailspin made it difficult to earn a living wage there.

Garcia arrived at the station with her year-old daughter and a cousin, Robert Granado, after a two-month journey from the city of Guarico through the Darién Gap, a 60-mile jungle trek that straddles the Colombia-Panama border. Garcia said she felt guilty about putting her daughter, Cataleya, through the dangerous journey but the toddler remained calm and in good spirits, despite a bout with fever.

“I’m happy,” Granado said as they waited for a bus to New York City. “The journey is over.”

At the other end of the Texas-Mexico border in Ciudad Juárez, a journey that has stretched for five months still isn’t over for Gloria Lobos of Guatemala. Lobos said she fled her physically abusive husband and settled in Chiapas in southern Mexico, where she worked on a farm and cleaned rooms at a hotel. In March, as the family walked to a grocery store, she said two men on a motorcycle attempted to kidnap her daughter.

After she reported the attempt to police, Lobos said the men returned days later with a gun and fired a shot at her daughter — the bullet missed. She said she raced to the bus station with her children and other relatives. Ciudad Juárez was the first ticket available.

Now she and her daughter live at a local shelter run by a Methodist church led by pastor Juan Fierro García, 65, while they wait for a CBP One appointment. The shelter has 63 migrants who will spend the night, down from 180 recently.

Sitting in a metal chair in the church, she said, “I never imagined God would want us to face this type of violence.”

In Glendale, Arizona, Kamala Harris — making her first visit to a border state since becoming the Democratic presidential nominee — touches on immigration 20 minutes into a 30-minute speech. It’s her fourth day of campaigning in swing states with running mate Gov. Tim Walz. She references her work as attorney general of another border state, California, and then repeats a line that Democrats have been espousing for many years.

“We know our immigration system is broken, and we know what it takes to fix it: Comprehensive reform that includes strong border security and an earned pathway to citizenship,” she says, sparking applause.

Harris jabs her Republican rival for the White House, former President Donald Trump, noting that he opposed a bill this year that would have, among other things, imposed asylum limits, added Border Patrol agents and changed asylum procedures to speed up decisions.

A short time later at a rally in Bozeman, Montana, Trump wastes no time getting to immigration, his signature issue. He uses “border” more than 30 times during his 100-minute speech.

Harris, he tells the crowd, “wants to allow millions of people to pour into our border through an invasion! … Four more years of crazy Kamala Harris means 50, probably it means 50 million illegal aliens pouring into our country.” (The Border Patrol has made about 7.1 million apprehensions from February 2021 through July 2024 — often the same person more than once — while an unknown number have eluded capture.)

Trump, who has promised mass deportations during his campaign, talks for several minutes about “illegal aliens” being sent to the U.S. from other countries’ prisons, a claim that lacks evidence. He connects migration with rising crime and speaks of migrants stampeding, overrunning, destroying, ruining, ravaging, preying.

After 11 p.m., he mentions the border for the last time: “Next year, America’s borders will be strong, sealed and secure. Promise.”