TEXAS, USA — Just about everybody in Texas agrees the child welfare system is broken. Where you’ll find the true disagreement is how to fix a system that’s been in disarray for decades.

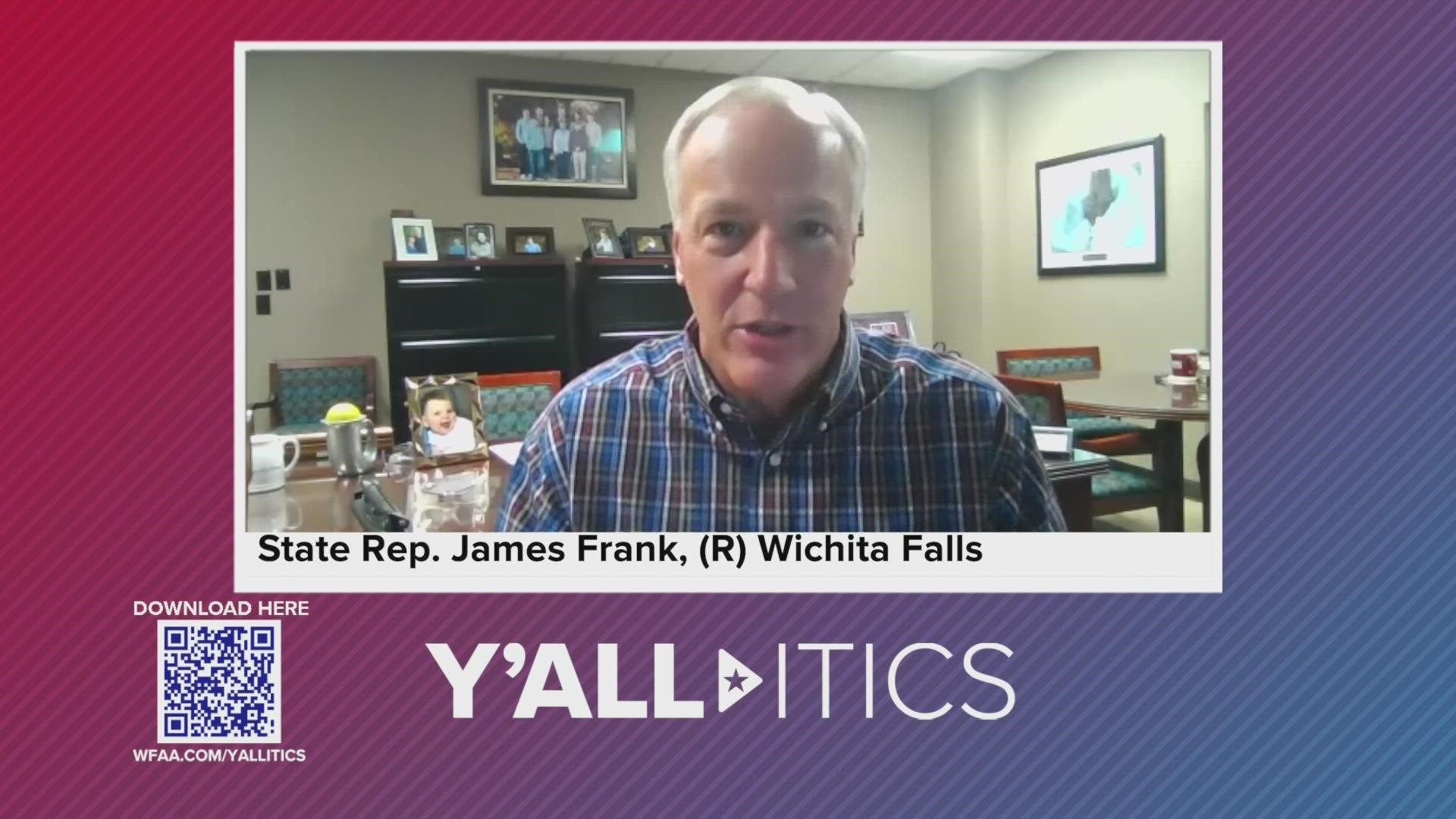

“When you actually look at some long-term trends, there are some good long-term trends. I wouldn’t say that on the whole, it is run significantly better now than it was 20-years ago, though,” State Rep. James Frank said on the most recent episode of Y’all-itics.

State Rep. James Frank is a Republican from Wichita Falls. As chairman of the House Human Services Committee, he is the lead lawmaker dealing with the child welfare system in Texas. But he also knows the system well because he has fostered and adopted two children.

Chairman Frank told WFAA the system in Texas still isn’t being run any better these days despite the fact the State has increased funding into the Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS) by a multiple of six over the last 20 years. DFPS is the umbrella organization that oversees the child welfare system in Texas, everything from child safety to foster and kinship care. So, an organization like Child Protective Services (CPS) reports to DFPS. And chairman Frank has been openly critical.

“The CPS system is made up of a whole lot of people who don't have children that want to tell everybody who has children, how to raise their children,” he said.

If chairman Frank represents the legislative side, Heidi Bruegel Cox is the insider. She’s been an attorney with the Gladney Center for Adoption in Fort Worth for nearly three decades. Cox thinks sometimes, the wrong questions are being asked in an effort to solve the wrong problems.

“I think the part of the brokenness is the people involved. Rep. Frank will say that we have a lot of young people trying to make these decisions and he is absolutely correct about that,” Cox said on Y’all-itics. “But we are trying to work this behemoth system, and we're not focusing on the individuals in the system, and I think that's one of the biggest issues.”

Recent reports have indicated the problems plaguing the child welfare system in Texas aren’t going away. Lawmakers were recently handed a DFPS report that said more than 100 children have died in the system since 2020. And child welfare workers continue to resign in noticeable numbers, despite pay increases. There were even accusations this year that an employee at a state-contracted shelter sold nude pictures of two girls staying at the facility.

So, what exactly is the state doing to try to help?

During the last legislative session, lawmakers passed a bill authored by Chairman Frank, HB 567, that changed the definition of neglect. To be clear, the legislation doesn’t change the abuse portion of the statute, only neglect. The Republican said Texas was removing far too many kids from the home.

“One of the reasons was there's tremendous difference in removal rates around the state," Rep. Frank said. "You had places that were removing at four times the state average. And they are not places that there's any indication that there's actually any more abuse. We just had extremely aggressive prosecution and judges pulling kids out for things that wouldn't even get a second look in other parts of the state."

But critics say the law has led to some cases where children who should have been removed were instead left in a home because of the new requirements for proof of neglect. Chairman Frank said this isn’t an unintended consequence. He told WFAA that’s the consequence they wanted.

“I think one of the things that nobody wants to admit is how much damage and how much trauma is caused by the act of removal itself,” Frank argued. “CPS, and I’ve seen it, operates under better safe than sorry. Better safe than sorry, so I better remove the kid just in case there's something bad might happen. Well, by definition, when you remove that child, something very bad just happened.”

Another complicating factor involves a federal lawsuit that’s been ongoing since 2011, when a group of child advocates sued the State. The judge ruled in 2015 that the State’s system was harming kids and needed to be reformed. So, she created two monitors to oversee the entire system. Think of them and their staff as watchdogs. And they are constantly making sure the State is following through on the reforms.

“I'm sure it's working in a lot of ways. But some people will say that it's also causing agencies not to take more difficult children, which is what led to CWOP,” said Cox.

CWOP stands for “children without placement.” And this is yet another problem now stressing the system. These are the most difficult children who enter the system, and they are the most likely to act out violently or sexually. But there is, literally at times, nowhere for these kids to go as the State struggles to find beds for them.

After receiving allegations of abuse at residential treatment centers across Texas who look after these high-risk kids, the State shut many of them down to investigate. But the State must now figure out where to put those kids and provide meaningful services. Cox and Frank say other existing agencies are afraid to step in and shelter those kids because of the increase scrutiny resulting from the lawsuit. And no new organizations are moving to the state to fill the void. Chairman Frank told WFAA there hasn’t been a dramatic rise in the number of these children, but instead a dramatic decline in the number of beds available.

“Money is not the only thing because literally some of these people are saying to us we don't care how much money you pay us, we will not operate if our whole entity is going to be put under heightened monitoring," said Rep. Frank. "We're not going to do it. Basically, you can't pay us enough to work with the state of Texas is what many of our providers are saying and then our CPS workers are saying the same thing."

The child welfare system in Texas is also going private, another attempt at a fix. Privatization has also been tried in a handful of other states, but Cox doesn’t believe anyone is getting it exactly right.

Texas lawmakers mandated this change back in 2017, one year after a spike in child deaths from abuse and two years after that federal judge determined foster care kids almost “uniformly leave state custody more damaged than when they entered.”

Cox said Texas is rolling out those changes regionally. Phase one was allowing those private companies to only offer foster care services. And in theory, they know what’s best for local kids, because they are a local company.

Phase two then allowed those private organizations to take over case management after the State removed a child.

“Has it worked the way everyone wanted? I don't think anyone believes that it does. It is definitely a broken apart system where every region will have a different organization managing it,” said Cox. “They're supposed to be working together and hopefully in the future they will continue to move into a good direction. It's hard to say today if we think it will be successful if we look back 10 years from now.”

State Rep. Frank said when lawmakers return to Austin for the next legislative session in January 2023, they’ll continue to look for more solutions. But he thinks beyond a legislative fix, the agencies themselves need to be run better. And he said they need to become much more efficient, and much faster, at implementing programs and changes.

The Republican also wants more services provided in the home for children and parents before removal. He said lawmakers provided two pilot programs to do just that during the last session (HB 3041), but implementation has been slow and incomplete.

“You know one of the challenges with the way the CPS system operates is you have to remove the child before you can provide services,” said Rep. Frank. “And when you think about it, so, I have to pull the child out of the home and then in many cases I'm going to tell the parent they have to go to parent training, which is like teaching somebody to swim when there's no water.”

Cox said her solution would start by forcing stakeholders in the system to think about each individual child and birth parent and ask what’s best for them. And she added that everyone who deals with those families must start communicating regularly. She told WFAA one example of why the system is broken is that some attorneys don’t even talk to the kids they’ve been assigned to represent.

“We have a system that has a CASA (court appointed special advocate), and an attorney ad litem, and a guardian ad litem and an attorney for each parent, and an attorney for the District Attorney and then the whole judicial program," Cox said. "Everyone is managing their own silo. And so, I think we need to require all the silos to get together with every child very regularly and communicate. I will say, I’m an attorney as part of the legal system, I see too many attorneys who never meet with their child clients. That is unacceptable.”