DALLAS — Even before President Joe Biden announced plans that the U.S. would accept 100,000 Ukrainian refugees displaced by Russia’s invasion, part-time Dallas resident Sara Phillips knew some would wind up in North Texas because of the region’s history of hosting such citizens.

“I just feel like we all have this part to play,” Phillips said on the most recent edition of Y’all-itics, a special early release. “And if we don’t carry our little load of the burden of the word, then someone else is carrying a double load.”

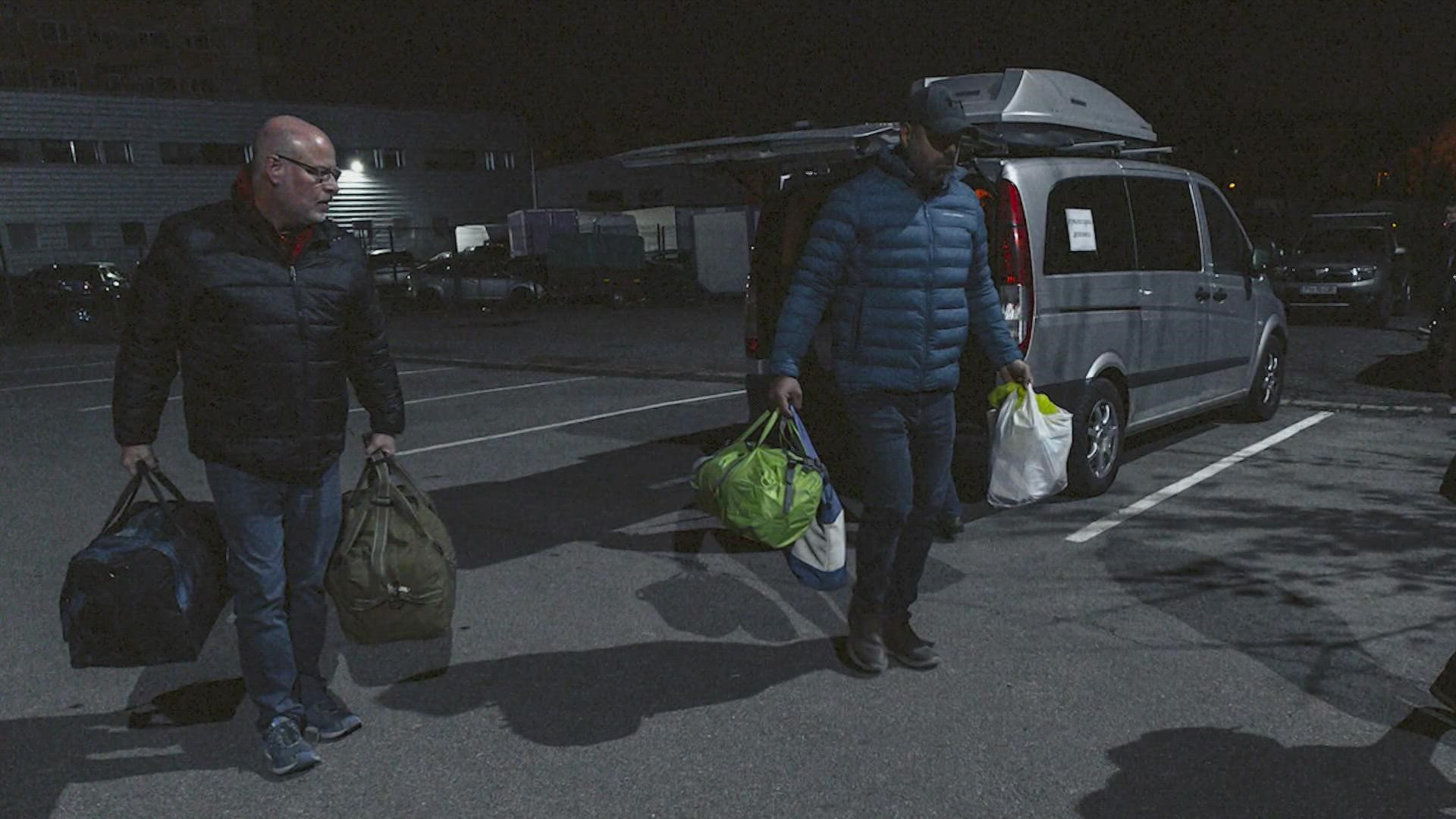

And few know the refugee crisis along Ukraine’s border better than Sara Phillips. She’s been on the ground in Moldova for nearly two weeks assessing how her organization, Medical Teams International, which provides basic medical care, should respond to the growing crisis that has no end in sight.

Phillips says she’s already seen both of ends of the emotional spectrum while dealing with folks who may have nothing left.

“Some people come across and you can see on their face a sense of relief like I made it. I made it to a safe place, that sense of relief. And some people come across weeping. They've just left everything. Their home. Their family. Their friends. Their jobs. Their identity. All their stuff,” said Phillips.

Phillips says it’s not just war and bombs they’re worried about now. It’s also illness, from COVID to colds.

There was even a recent polio outbreak in Ukraine and since the war completely halted the vaccination campaign underway to end it, there are fears that disease is coming across the border, too.

And then there are the unthinkable decisions facing folks every single day.

“There was this one story I was told at the refugee center of a family that had sat down for dinner, food on the table, and their neighbors who had a car called and said we're leaving, we're going to Moldova. We have room for you if you want to come with us, but you have to decide in the next three minutes. When I thought to myself, three minutes? I mean I travel all the time and I'm not entirely sure I could find my own passport in three minutes. What do you grab with that kind of timeline?” she asked knowing she had no clear answer.

Phillips says around 100,000 Ukrainian refugees remain in Moldova, just a third or so of the total number to pass through the country before moving on to other locations.

But Moldova is a smaller country to Ukraine’s southwest, and it is Europe’s poorest. If the same number of Ukrainian refugees that have flooded Moldova, -- percentage-wise -- suddenly crossed into Texas, it would be the equivalent of around three million people, with just under a million or so deciding to stay.

While there are some fears, she says, about the enormous influx of people pushing the country’s capacity to the limit, Moldovans have been more than generous and show no signs of strain.

“I have been so humbled by the response of Moldovans,” Phillips said. “It is astounding that of their little, they have been so incredibly generous. It’s absolutely amazing the amount of generosity and compassion people have.”