AUSTIN, Texas — This story was originally published by our content partners at the Texas Tribune. You can read the original article here.

Under scrutiny for spending the duration of Hurricane Beryl 8,000 miles away on an economic development trip to Asia, Gov. Greg Abbott is defiant — insisting his absence did nothing to hinder Texas’ disaster response.

The governor and his aides say they were in constant communication with emergency leaders and Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick, who assumed the role of acting governor and will briefly do so again this week when Abbott departs for the Republican National Convention in Milwaukee. They insist state officials met every local need that arose, requested federal aid without delay and ran a well-oiled machine — seasoned by past storms like Hurricane Harvey.

Still, Abbott’s absence prompted a wave of unflattering headlines and editorials blasting his trip, and Texas Democrats are now calling for the governor to skip the convention, rather than “jetting off to applaud Donald Trump while Texans are still suffering” from power outages and property damage.

Abbott, who has ignored the convention crossfire, said his trip across the Pacific allowed him to build ties with political and business leaders in Taiwan, South Korea and Japan that will pay off down the road, bringing jobs and new economic ventures from those countries’ lucrative semiconductor industries.

“It's easy to play Monday-morning quarterback in these situations,” said Matt Hirsch, a former deputy chief of staff to Abbott, in an interview with The Texas Tribune. “But looking at the bigger picture, the governor is still governor no matter where he goes. We live in a day and age now where you don't have to be there on the ground to do the necessary things to respond to a storm like this.”

Abbott came away from the trip with few concrete economic deals to publicly tout. The two biggest tangible announcements — a new state office to support trade and investment in Taiwan and plans for a South Korea-based company to build a superalloy facility in Texas — could have happened regardless of Abbott’s trip, leaving him to tout bolstered “economic and cultural partnerships” and the hope of future business deals. But Hirsch said that’s exactly how these trips work: rather than an immediate multibillion-dollar announcement, Texas might see a major investment several months or a year down the road.

“Relationships matter,” Hirsch said. “There's nothing more impactful from an economic development standpoint than showing up. I think that matters a great deal to the companies over there, the traditions and the cultures. It is a source of pride and it is a tremendous deal.”

Abbott’s critics say he should have postponed the trip until the storm passed, or at least cut it short once he saw the scale of the disaster, which included more than 2 million power outages, widespread property damage and a growing death toll. In defending the state’s response, Abbott has trained his fire on CenterPoint — the Houston-based utility company whose customers bore the brunt of the blackouts — and ordered an investigation into the prolonged outages.

Among those piling on against the governor was President Joe Biden, who accused Abbott and Patrick of taking too long to request a disaster declaration that would unlock federal aid for an array of emergency services and supplies, including debris removal and generators.

Matt Angle, a veteran Texas Democratic strategist, said it was “arrogant and disrespectful to Texans” for Abbott to leave, even if he and his staff were able to communicate with the right folks back home.

“ It wasn't just a matter of his physical presence. It needed his 100% focus,” Angle said. “Instead, he was contemplating the dessert at one of his nice dinners in East Asia.”

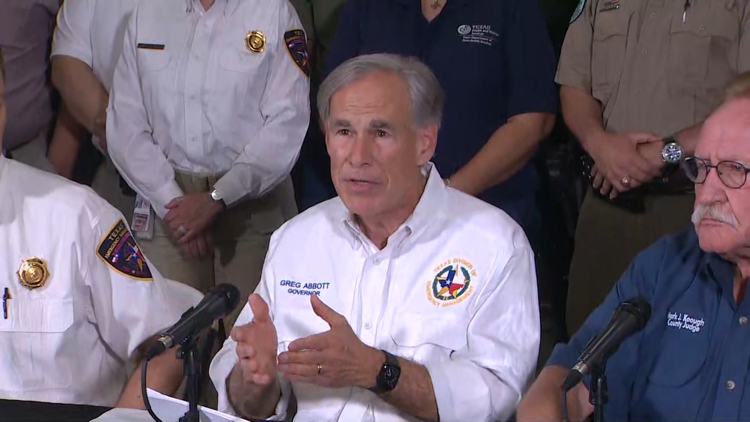

At a Sunday press conference, his first public appearance since returning to Texas, Abbott said that “had I been here the entire time, there'd be absolutely nothing that would be any different.” Patrick also insisted there was “no delay” in seeking the disaster declaration, and he condemned Biden for “turning Hurricane Beryl into a political issue.”

Abbott’s trip

Abbott left for Asia on July 5, when Beryl had reached Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula and was projected to make landfall somewhere between Corpus Christi and Matagorda, likely as a Category 1 or 2 hurricane. By the time it reached the coast early the morning of July 8, it was clear the Houston area — a metro area of more than 7 million, home to Texas’ biggest city and county — would see some of Beryl’s nastiest rain and wind.

Four Abbott aides, who were authorized to provide details on background about the Asia trip and storm response, offered no indication that Abbott ever considered pushing back the Asia trip or returning early. They reiterated Abbott’s statement that the response would have been exactly the same if the governor had stayed, and said his office made sure everything was in place before the storm, with resources and personnel from various state agencies deployed or ready to respond.

Three Abbott aides involved in the disaster response said the governor’s senior staff checked in regularly with Patrick and his office before, during and after Beryl. They said Abbott’s office also played air traffic controller connecting local governments and the private sector with state agencies, and kept tabs on agencies to ensure they were handling routine functions — such as asking the Biden administration to let recipients of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, commonly known as food stamps, apply for replacement benefits if they lost food in the storm.

Some Texas agencies were aided by muscle memory from prior storms, one of the aides said, describing how the nuts and bolts of the Beryl response churned along as usual, several layers below whoever was at the top. The Department of Motor Vehicles, for example, temporarily suspended permitting requirements for oversize and overweight vehicles helping deliver supplies and equipment for the storm.

“Over the years, this playbook has been so efficiently and effectively put together, it in some ways runs on its own,” said Hirsch, who helped guide Abbott’s office’s public response to Harvey in 2017. “The people who are in the room have been there for all these years, and they have all the [background] information” and contacts with local officials from past storms.

"Return for the investment"

Abbott has said the trade mission “helped strengthen our economic and cultural partnerships” with Taiwan, South Korea and Japan, as he met with executives and top government officials there to promote Texas as a good fit for new business development. The governor was accompanied by an entourage of five state lawmakers, Secretary of State Jane Nelson and 23 Texas business and community leaders, many of them heads of local chambers of commerce and city economic development corporations.

Planning for the event began several months ago, culminating in about 30 events and meetings across four cities, according to an Abbott aide. The trip was sponsored and paid for by the Texas Economic Development Corporation, a nonprofit that markets the state for economic development.

The Taiwan stop, Abbott’s first, centered around an announcement that Texas would open a state office there to promote “more trade, investment, and collaboration” between Texas and Taiwan. The Legislature earmarked $800,000 in the latest state budget to pay for the office.

State Sen. Carol Alvarado, a Houston Democrat who joined Abbott for the Taiwan portion of his trip, also had to juggle storm response while overseas. She said she was on the phone multiple times a day with her staff, who hosted a handful of food and ice distribution events in the district, which covers parts of north and central Houston and a wide swath of east Harris County.

Alvarado noted that her trip — planned well before the hurricane — was arranged separately from Abbott’s at the behest of the Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in Houston and state Rep. Angie Chen Button, a Richardson Republican who immigrated to Texas from Taiwan. Their trip, also to mark the Taiwan office opening, ended up coinciding with Abbott’s, so they all linked up.

She said Taiwan, already a top trading partner with Texas to the tune of $21 billion last year, poses plenty of opportunity for the state. But it will also be important, Alvarado said, “to show some return for the investment” of state dollars spent to set up the Taiwan office.

“The Legislature has invested some money to open up that office there, and we need to make sure that we have the right people on the ground — [so] that in two years, we can show what the benefits were for that investment,” Alvarado said.

Abbott met with Taiwan President Lai Ching-te and signed an informal statement of intent with the economic affairs minister to work together on semiconductor, electric vehicle and “energy resilience” trade and investments. Then it was on to South Korea, where Abbott announced SeAH Group, a South Korea-based steel company, would build a $110 million superalloy manufacturing plant in Temple.

Throughout the trip, Abbott met with business leaders whose companies had already established a foothold in Texas. In South Korea, he linked up with executives who last year opened a manufacturing facility for electric vehicle charging stations in Plano; and toured Samsung’s massive semiconductor production hub in Pyeongtaek. The electronics giant is expected to drop upwards of $40 billion building a cluster of chip-making and research facilities in Taylor.

Abbott rounded out the trip in Japan, where he signed another symbolic statement with the governor of Aichi prefecture to “encourage more trade in critical industries and attract new business” to Texas. The industrial region includes a number of transportation manufacturing companies, among them Toyota’s global headquarters. Abbott met with the company’s executives last week and “discussed more opportunities for Toyota to invest in Texas,” according to the governor’s office.

Biden enters the fray

Abbott’s absence from the hurricane was magnified after Biden entered the conversation, asserting directly to the Houston Chronicle that federal aid was being delayed because Texas officials did not more quickly ask for a federal disaster declaration.

Abbott and Patrick have vehemently denied they were slow to react, pointing the finger back at the Biden administration.

Some of the confusion may stem from the arcane distinction between federal “emergency” and “major disaster” declarations. Abbott and other governors have often requested the lesser “emergency” declarations when comparable storms were still barreling toward the coast; Abbott did so in 2020 for Hurricane Hanna and Hurricane Laura when the latter was still a tropical storm. TDEM and FEMA both note the governor “may request an emergency declaration in advance or anticipation of the imminent impact” of a major storm.

These “emergency” declarations can provide the same type of aid — debris removal and “emergency protective measures” — granted to Texas under the major disaster declaration Biden eventually approved, according to FEMA. They can also serve as stopgaps, providing faster relief before a state is issued the more extensive “major disaster” declaration. But Texas did not appear to have requested either an emergency or major disaster declaration until July 9, some 30 hours after Beryl had made landfall the day before.

Angle, who maintained that Abbott had botched the Beryl response, said the governor had done the same in the wake of enough prior disasters — such as the Uvalde school shooting, he said — that “this is now a feature and not a bug.”

“Disaster after disaster, Greg Abbott doesn't handle it very well,” Angle said.

At the Sunday press conference with Abbott, Nim Kidd, chief of Texas Division of Emergency Management, said the debate was irrelevant — “we are wasting effort right now talking about” it — because TDEM was able to fulfill all the aid requests they received from local officials. Abbott’s office said Monday the state has been providing backup generators, tarps and fuel and had distributed several million bottles of water, more than 800,000 meals and more than 200,000 bags of ice.

“There was not a piece of equipment, not a bottle of water or not a meal ready to eat that we did not have available for our local partners,” Kidd said.