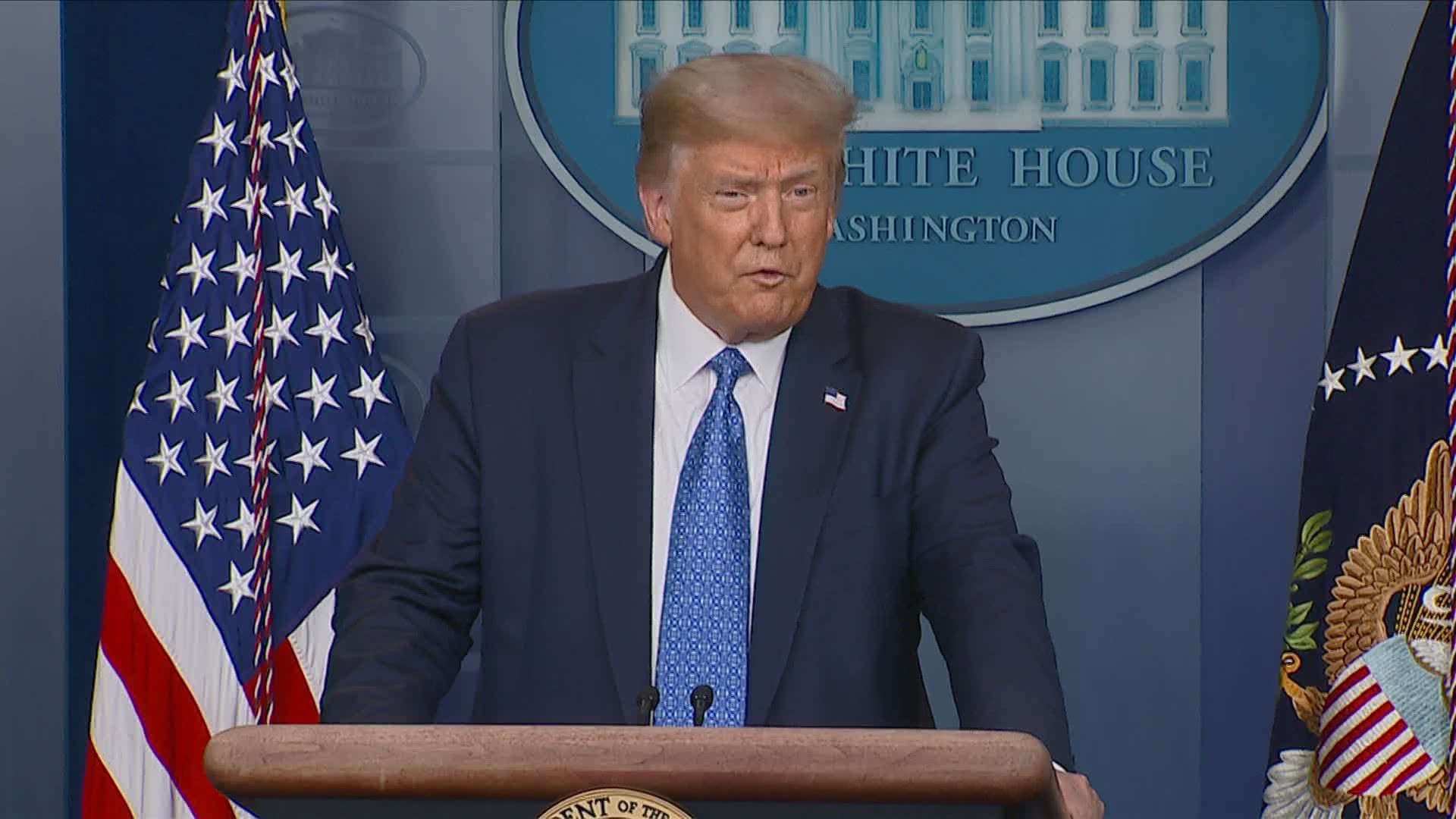

WASHINGTON — President Donald Trump announced Wednesday that he will send federal agents into Chicago and Albuquerque to help combat rising crime, expanding the administration’s intervention in local enforcement as he runs for reelection under a “law-and-order” mantle.

Using the same alarmist language that he has employed in the past to describe illegal immigration, Trump painted Democrat-led cities as out of control and lashed out at the “radical left," even though criminal justice experts say the increase in violence in some cities defies easy explanation.

“In recent weeks there has been a radical movement to defend, dismantle and dissolve our police department,” Trump said at a White House event, blaming the movement for “a shocking explosion of shootings, killings, murders and heinous crimes of violence."

“This bloodshed must end," he said. “This bloodshed will end.”

The decision to dispatch federal agents to American cities is playing out at a hyperpoliticized moment when Trump is trying to show that he stands with law enforcement and depict Democrats as weak on crime. With less than four months to go before Election Day, Trump has been serving up dire warnings that the violence would worsen if his Democratic rival Joe Biden is elected in November, as he tries to win over voters who could be swayed by that message.

In trying to explain the spike in violence, experts point to the unprecedented moment the country is living through — a pandemic that has killed more than 140,000 Americans, historic unemployment, stay-at-home orders, a mass reckoning over race and police brutality, intense stress and even the weather. Compared with other years, crime is down overall.

Local authorities have also complained that deploying federal agents to their cities has only exacerbated tensions on the streets.

Hundreds of federal agents already have been sent to Kansas City, Missouri, to help quell a record rise in violence after the shooting death of a young boy there. Sending federal agents to help localities is not uncommon. Barr announced a similar surge effort in December for seven cities that had seen spiking violence.

Usually, the Justice Department sends agents under its own umbrella, like agents from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives or the Drug Enforcement Agency. But this surge effort will include at least 100 Department of Homeland Security Investigations officers working in the region who generally conduct drug trafficking and child exploitation investigations.

DHS officers have already been dispatched to Portland, Oregon, and other localities to protect federal property and monuments as Trump has lambasted efforts by protesters to knock down Confederate statues.

But civil unrest in Portland only escalated after federal agents there were accused of whisking people away in unmarked cars without probable case.

The spike in crime has hit hard in some cities with resources already stretched thin from the pandemic. But local leaders initially rejected the move to send in federal forces.

Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot later said she and other local officials had spoken with federal authorities and come to an understanding.

“I’ve been very clear that we welcome actual partnership,” the Democratic mayor said Tuesday after speaking with federal officials. “But we do not welcome dictatorship. We do not welcome authoritarianism, and we do not welcome unconstitutional arrest and detainment of our residents. That is something I will not tolerate.”

In New Mexico, meanwhile, Democratic elected officials were cautioning Trump against any possible plans to send federal agents to the state, with U.S. Sen. Martin Heinrich calling on Bernalillo County Sheriff Manny Gonzales, who will be at the White House on Wednesday, to resign.

“Instead of collaborating with the Albuquerque Police Department, the Sheriff is inviting the President’s stormtroopers into Albuquerque,” the Democratic senator said in a statement.

But federal gun crimes generally carry much stiffer penalties than state crimes — and larger-scale federal investigations that can cross state lines tend to make a big impact.

The Justice Department will reimburse Chicago $3.5 million for local law enforcement’s work on the federal task force. Through a separate federal fund, Chicago received $9.3 million to hire 75 new officers.

Two dozen agents will be sent to Albuquerque, and the administration made available $1.5 million in funding for the Bernalillo County Sheriff’s Department for five new deputies and $9.4 million for 40 new Albuquerque officers.

In Kansas City, the top federal prosecutor said any agents involved in an operation to reduce violent crime in the area will be clearly identifiable when making arrests, unlike what has been seen in Portland.

“These agents won’t be patrolling the streets,” U.S. Attorney Timothy Garrison said. “They won’t replace or usurp the authority of local officers.”

Operation Legend — named after 4-year-old LeGend Taliferro, who was fatally shot while sleeping in a Kansas City apartment late last month — was announced on July 8. The first arrest came earlier this week.

Garrison has said that the additional 225 federal agents from the FBI, DEA, ATF and the U.S. Marshals Service join 400 agents already working and living in the Kansas City area.

The Trump administration is facing growing pushback in Portland. Multiple lawsuits have been filed questioning the federal government's authority to use broad policing powers in cities. One suit filed Tuesday says federal agents are violating protesters’ 10th Amendment rights by engaging in police activities designated to local and state governments.

Oregon’s attorney general sued last week, asking a judge to block federal agents’ actions. The state argued that masked agents had arrested people on the streets without probable cause and far from the U.S. courthouse that’s become a target of vandalism.

Federal authorities, however, said state and local officials had been unwilling to work with them to stop the vandalism and violence against federal officers and the U.S. courthouse.

___

Associated Press writers Michael Tarm in Chicago and Michael Balsamo in Washington contributed to this report.