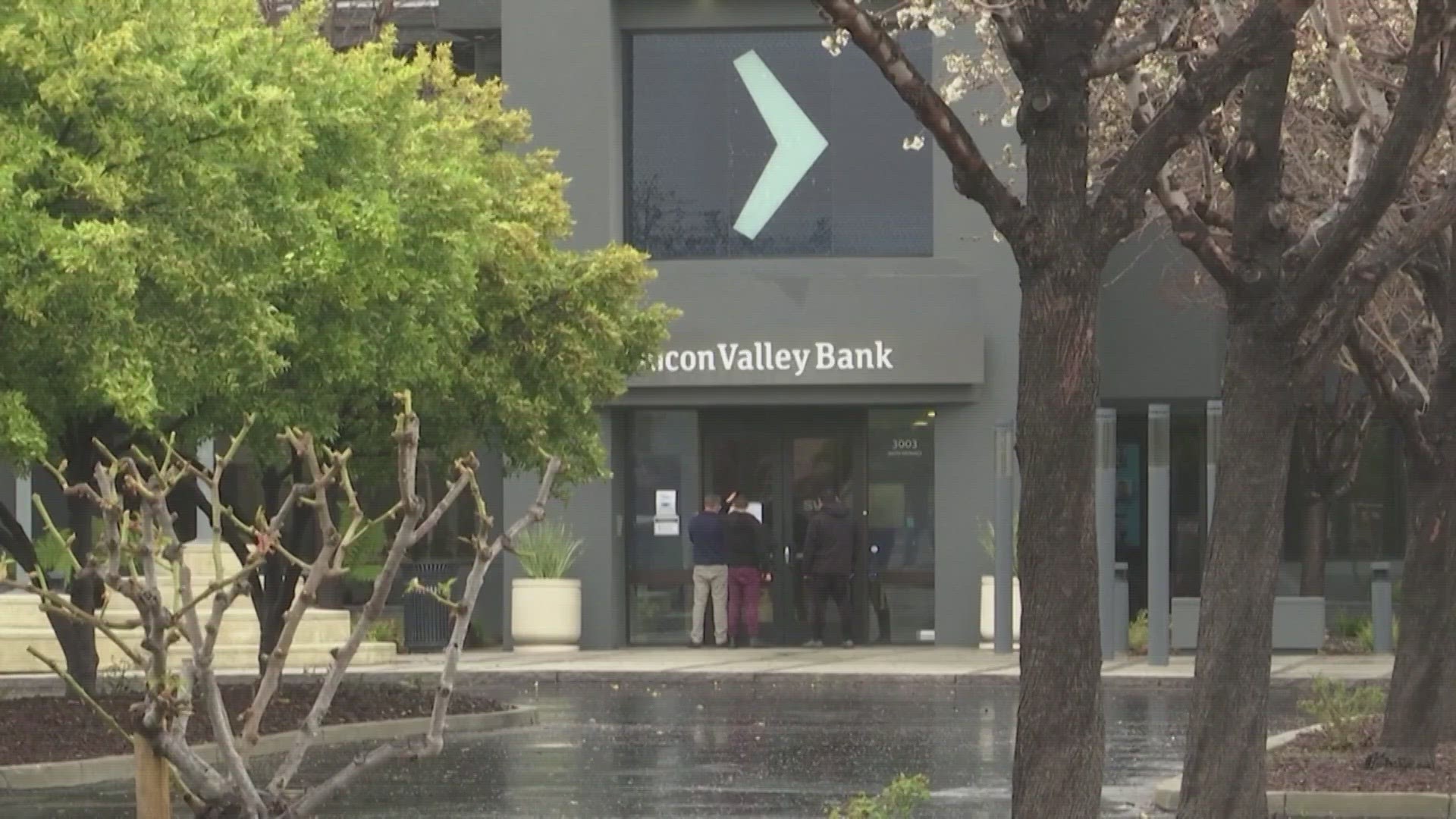

DALLAS — The U.S. Treasury said Sunday evening that it would fully protect all deposits at Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), which failed Friday after customers made a run to withdraw money.

Bill Tyler is the director of operations at TWG Supply in Grapevine. The business itself doesn’t use SVB, but its payroll processor does – or did.

“I got a text at 6:30 in the morning that said, 'Hey Bill, I didn’t get my paycheck. Can you look into this for me?'” Tyler said. "I’d never heard of SVB before probably 10 o’clock on Friday morning."

The 18-employee company distributes airplane boarding bridges, baggage handling equipment and more airline equipment. They’re one of countless companies impacted by Silicon Valley Bank’s failure.

SVB had nearly $200 billion dollars in deposits, making it the 16th largest bank in the country and second largest bank failure ever. Washington Mutual was the largest bank failure in U.S. history when it collapsed during the Great Recession.

“I don’t know that I would’ve done anything different if I would’ve known that it was at SVB. I don’t know to distrust banks,” he said.

SVB’s failure began because its clients had a lot of deposits but made few loans.

To make money, it bought government bonds. As interest rates rose, though, the bond bought at low interest rates began to rack up billons of dollars in unrealized losses.

At the same time, more of the bank’s clients were making withdrawals. That meant SVB had to sell those investments at a massive loss to cover the deposits. That disclosure made customers nervous and sparked a $42 billion run on the bank in one day.

On Sunday, the Federal Reserve said it would cover all deposits, even those over $250,000, meaning they wouldn’t otherwise be covered by the FDIC’s deposit insurance.

That includes companies like Roku, which had roughly $500 million in cash at the bank, Etsy, and even Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drugs, which Cuban said on Twitter had several million dollars in the bank.

“Many people were very understanding, but I took everybody to lunch because I didn’t want anyone to think, 'I don’t have money in the bank, I can’t eat today,'” Tyler said.

It’s been nearly 1,000 days since the last bank failure, and the latest could spark a push for more regulation and more consolidation if customers move deposits from mid-size banks to larger ones.

For Tyler, the next step is just getting work back to normal.

"I need to spend next week reassuring our employees that this won’t happen again,” he said.