WASHINGTON — Rising U.S. consumer prices moderated again last month, bolstering hopes that inflation’s grip on the economy will continue to ease this year and possibly require less drastic action by the Federal Reserve to control it.

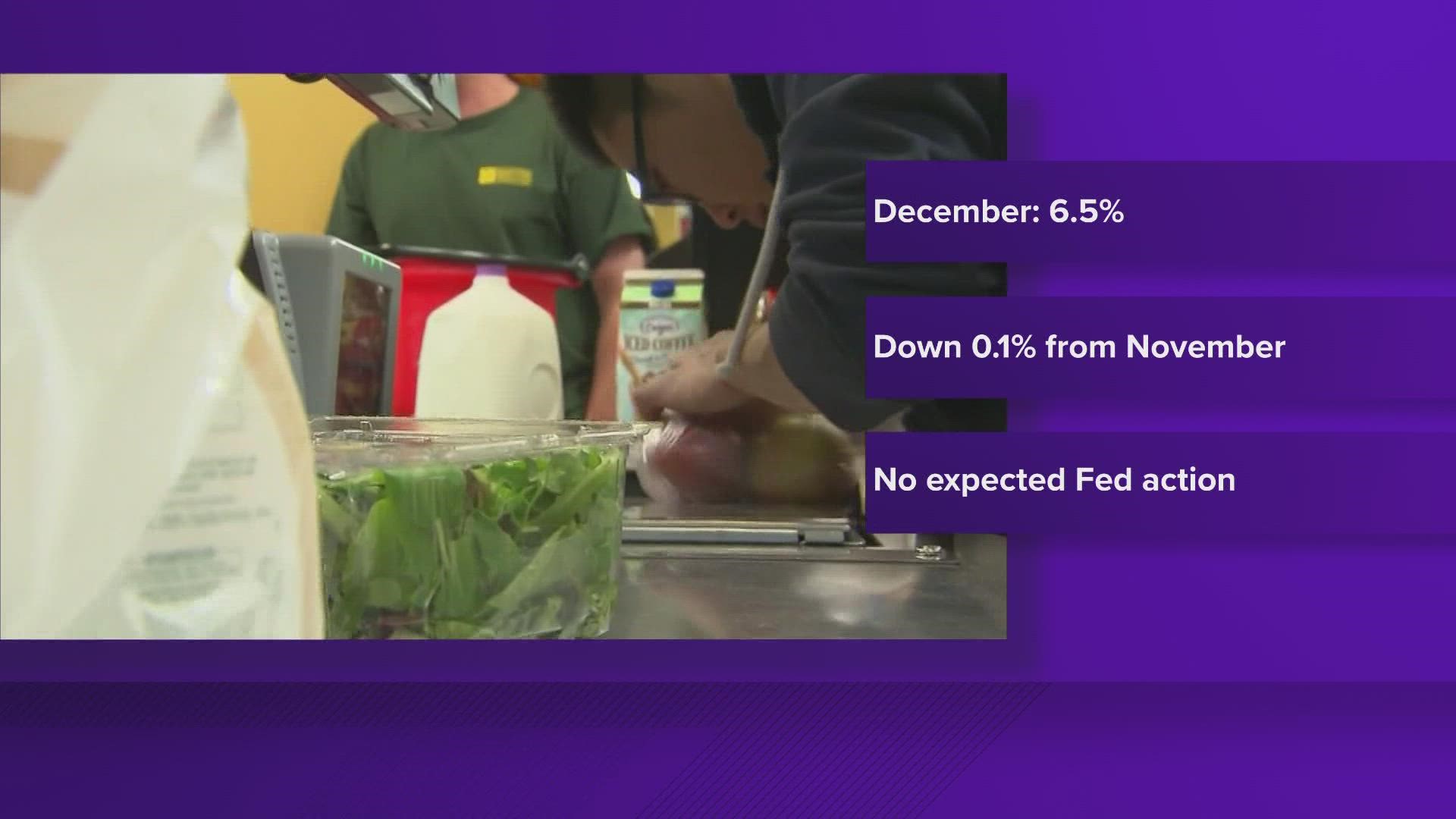

Inflation declined to 6.5% in December compared with a year earlier, the government said Thursday. It was the sixth straight year-over-year slowdown, down from 7.1% in November. On a monthly basis, prices actually slipped 0.1% from November to December, the first such drop since May 2020.

The softer readings add to growing signs that the worst inflation bout in four decades is gradually waning. Still, the Fed doesn’t expect inflation to slow enough to get close to its 2% target until well into 2024. The central bank is expected to raise its benchmark rate by at least a quarter-point when it next meets at the end of this month.

Excluding volatile food and energy costs, so-called core prices rose 5.7% in December from a year earlier, slower than the 6% year-over-year increase in November. From November to December, core prices increased just 0.3%, the third straight monthly slowdown, after rising 0.2% in November.

Even as inflation gradually slows, it remains a painful reality for many Americans, especially with such necessities as food, energy and rents having soared over the past 18 months.

Grocery prices rose 0.2% from November to December, the smallest such increase in nearly two years. Still, those prices are up 11.8% from a year ago.

Behind much of the decline in overall inflation are falling gas prices. The national average price of a gallon of gas has tumbled from a $5 in June to $3.27 as of Wednesday, according to AAA.

Also contributing to the slowdown are used car prices, which fell for a sixth straight month in December. New car prices declined, too. The cost of airline tickets and personal care such as haircuts also dropped.

Supply chain snarls that previously inflated the cost of goods have largely unraveled. Consumers have also shifted much of their spending away from physical goods and instead toward services, such as travel and entertainment. As a result, the cost of goods, including used cars, furniture and clothing, has dropped for two straight months.

Last week’s jobs report for December bolstered the possibility that a recession could be avoided. Even after the Fed’s seven rate hikes last year and with inflation still high, employers added a solid 223,000 jobs in December, and the unemployment rate fell to 3.5%, matching the lowest level in 53 years.

At the same time, average hourly pay growth slowed, which should lessen pressure on companies to raise prices to cover their higher labor costs.

Another positive sign for the Fed’s efforts to quell inflation is that Americans overall expect price increases to decline over the next few years. That is important because so-called “inflation expectations” can be self-fulfilling: If people expect prices to keep rising sharply, they will typically take steps, like demanding higher pay, that can perpetuate high inflation.

On Monday, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York said that consumers now anticipate inflation of 5% over the next year. That’s the lowest such expectation in nearly 18 months. Over the next five years, consumers expect inflation to average 2.4%, only barely above the Fed’s 2% target.

Still, in their remarks in recent weeks, Fed officials have underscored their intent to raise their benchmark short-term rate by an additional three-quarters of a point in the coming months to just above 5%. Such increases would come on top of seven hikes last year, which led mortgage rates to nearly double and made auto loans and business borrowing more expensive.

Futures prices show that investors expect the central bank to be less aggressive and implement just two quarter-point hikes by March, leaving the Fed’s rate just below 5%. Investors also project that the Fed will cut rates in November and December, according to the CME FedWatch Tool.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell has sought to push back against that expectation of fewer hikes this spring and cuts by the end of the year, which can make the Fed’s job harder if investors bid up stock prices and lower bond yields. Both trends can support faster economic growth just when the Fed is trying to cool it down.

The minutes from the Fed’s December meeting noted that none of the 19 policymakers foresee rate cuts this year.

Still, last week James Bullard, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, expressed some optimism that this year, “actual inflation will likely follow inflation expectations to a lower level,” suggesting 2023 could be a “year of disinflation.”