WASHINGTON — Brittney Griner is easily the most prominent American locked up by a foreign country. But the WNBA star's case is tangled up with that of a lesser-known American also imprisoned in Russia.

Paul Whelan has been held in Russia since his December 2018 arrest on espionage charges he and the U.S. government say are false. He was left out of a prisoner exchange in April that brought home yet another detainee, Marine veteran Trevor Reed. That has escalated pressure on the Biden administration to avoid another one-for-one swap that does not include Whelan — even as it presses for the release of Griner, an Olympic gold medalist whose case has drawn global attention.

For Griner and Whelan, the other's case injects something of a wild card into their own, for better or worse.

The U.S. government may not agree to a deal in which just one of them is released, potentially complicating negotiations. But Whelan could also benefit from the attention given to Griner, which has cast a spotlight on his case. And though the U.S. may hesitate to give up a high-level Russian prisoner in exchange for Griner, who's charged with a relatively minor drug offense, it's possible it would be more inclined to do so if both she and Whelan were part of any deal.

The potential interplay between the cases is not lost on the families and supporters of Whelan and Griner.

“It's still very raw,” Whelan's sister, Elizabeth Whelan, said of her brother being excluded from the Reed deal. “And to think we might have to go through that again if Brittney is brought home first is just terrible.”

But “what's really bad” about feeling that way, she hastened to add, is that she and her family absolutely want Griner released, too. “It's not like we don't want her home. We want everyone out of there, out of Russia and away from that situation.”

It all adds up to a “sticky wicket,” said Kimberly St. Julian-Varnon, a doctoral student at the University of Pennsylvania who specializes in Russia and is advising the WNBA players' association on Griner's case.

If Griner were to leapfrog Whelan in coming home, the administration will face scrutiny from Whelan's supporters. “And if Paul Whelan gets out first, you're going to have questions about why isn’t Brittney out when Brittney hasn't even been convicted yet,” she said.

U.S. officials have not said whether swaps are being discussed that could get Griner, Whelan or both home, or whether they’d accept a deal that yields the release of one without the other. A spokesman for the State Department office that advocates for wrongfully detained Americans, the Special Presidential Envoy for Hostage Affairs, or SPEHA, declined to say how the cases might affect each other but said in a statement that the office remains committed to securing the release of both.

There's no question that the February arrest of Griner — Russian authorities detained her at an airport after they said a search of her bag revealed vape cartridges containing oil derived from cannabis — has heightened public awareness around the dozens of Americans who, like Reed and Griner, are classified as wrongfully detained by foreign governments.

The seven-time WNBA All-Star is not only one of the most dominant figures in her sport but also a prominent gay, Black woman. That has prompted questions about the role race and sexual identity are playing in a country where authorities have been hostile to the LGBTQ community, and about whether her case would get more attention if it involved a white male athlete.

U.S. officials and Griner’s supporters initially said little publicly about her case, but that changed in May when the State Department designated her as wrongfully detained and transitioned her case to the SPEHA office.

Griner's wife, Cherelle, urged the Biden administration in an interview with ABC's “Good Morning America” to do anything necessary to get Griner home, but also expressed empathy for Whelan. She said that even though there's no connection between the two besides the fact they're both in Russia, “I obviously want him back, too.”

Griner’s fame cuts both ways, said St. Julian-Varnon. If ever Russia wants to reestablish itself as a country hospitable to foreign athletes like Griner, the country would have significant incentive to release her. But given Griner's “political value” to Russia, it may also make a huge demand for her release.

“This is the biggest chip that they have to play,” she said.

Tamryn Spruill, a freelance journalist and author who launched a Change.org petition demanding Griner's freedom, said in an email that if her “case can be leveraged to simultaneously secure Whelan’s release — or vice versa — then it is my hope that the president will exploit all of those avenues.”

Unlike Griner, who is awaiting trial, Whelan has been convicted and sentenced.

A corporate security executive from Michigan who was arrested after traveling to Russia for a wedding, Whelan was found guilty in 2020 and sentenced to 16 years in prison. He and his family have vigorously asserted his innocence. The U.S. government has denounced the charges as false.

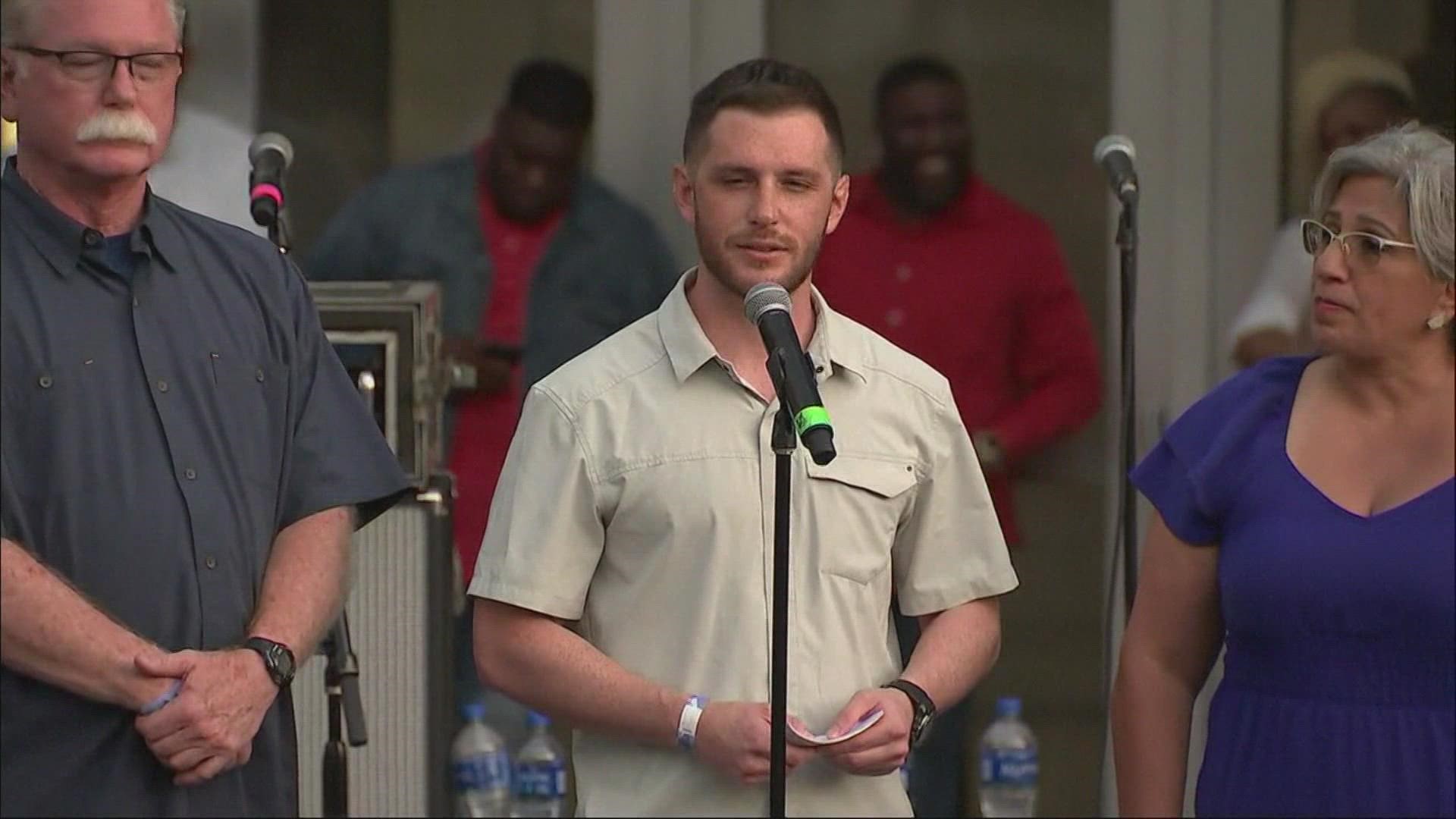

Reed had also been sentenced well before the swap that freed him. He had been jailed over what Russian authorities say was a drunken physical encounter with police in Moscow and was freed in exchange for Konstantin Yaroshenko, a Russian pilot who was serving a 20-year sentence for drug trafficking conspiracy. U.S. officials cited in part Reed's ailing health as justification for the trade.

It's not clear which other Russians, if any, might be part of additional exchanges. Russian state media have for years floated the name of notorious arms dealer Viktor Bout, though such a deal risks being seen as lending false equivalency between a Russian the U.S. government regards as properly convicted and Americans it considers unjustly detained.

Jonathan Franks, a consultant who worked on the Reed case, said it was hard to envision a Griner-Bout deal or a Griner deal that didn't involve Whelan.

“I truly believe Brittney Griner's fastest path out of Russia is on Air Whelan,” he said.

Elizabeth Whelan said the early morning call she had to make to her aging parents to tell them Reed was coming home but her brother was not is not an experience she wants to repeat. But she said her family does understand the possibility one prisoner could be freed without the other.

“We’re faced with a situation where these hostile foreign nations can assign different values to each person they’re holding, and can work separate deals. Whichever deal comes through first is often who comes home first,” she said, “and it’s not at all a tenable situation.”