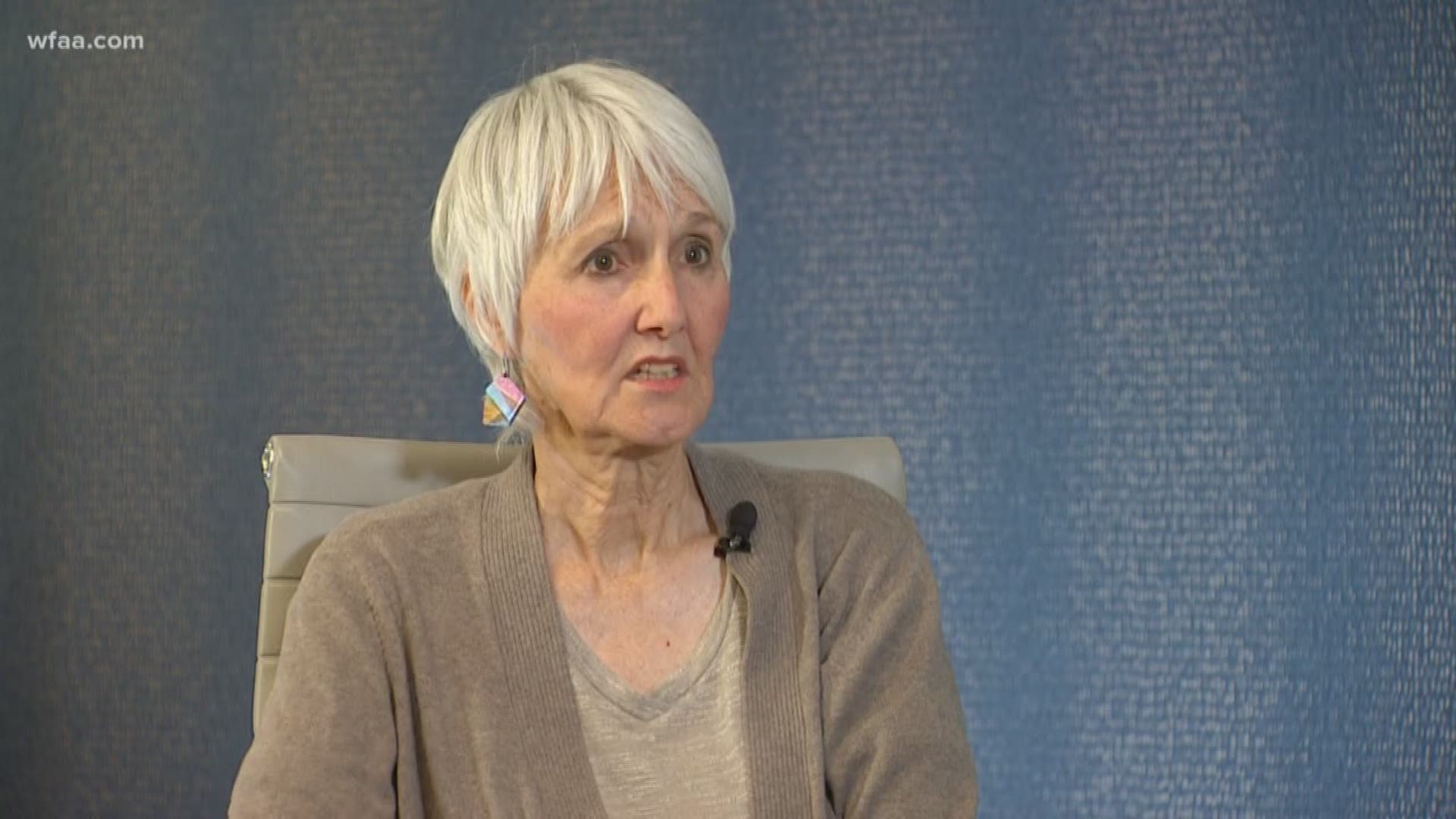

DALLAS — Almost 20 years have passed since Sue Klebold’s son altered countless lives in horrible ways.

“Dylan was the kind of a child that you wouldn’t think would be capable of this,” she said. “He was in the gifted program. He was a nice kid, and I want to make people aware that what you see is not always what is.”

Klebold was in Dallas on Thursday to speak at a fundraising event for Mental Health America of Greater Dallas. Talking openly about what happened is her way of trying to keep it from happening again.

On April 20, 1999, her son and a friend entered Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, where they were seniors. They shot and killed 12 classmates and a teacher, injured two dozen other people, and then killed themselves. “I never stopped loving him. The love was always the thing that remained,” she said. “I hated what he did, but I never hated him."

An investigation revealed that the boys had been plotting and planning for months. WFAA asked Klebold if, when she looks back, she can pinpoint red flags she missed and mistakes she made.

“Well, first of all, I don’t know of any parent that doesn’t make mistakes, so of course I made mistakes, and I think yes, I did miss signs,” she said.

“Dylan did have a change in behavior in his junior year of high school,” she said, describing one of the signs she overlooked. “He’d never been in trouble before, but he was suddenly in trouble with a cluster of things that he did.”

“He had a friendship that was very toxic, and I was not aware of the nature of that friendship,” she said.

“I think we tend to feel, especially as moms, that if we love our children enough, that our love is protective, that we can keep them from ever wanting to die, ever wanting to kill, ever having a mental illness,” she said. “Love is not enough. These things happen despite our love and caring.”

Her other lesson for parents is to talk less and hear more. “We so often are trying to help our kids feel better, trying to advise them, and especially nowadays youth are so burdened by dark thoughts and fears and anger. We have to learn how to allow them to give voice to these without interjecting our own desires to fix it,” she said.

“The most important gift we can give them is to listen and encourage them to speak and no matter what they say, be receptive and say - tell me more, I want to know more about that.”

Klebold experienced PTSD and panic attacks after the shooting. She said there were times she curled up in a ball, unable or unwilling to face reality.

She began to research mental health, suicide and violence to try to better understand what she was going through and what her son might have been battling, too.

She wrote a book, donates the profits, and now advocates for mental health awareness, research and suicide prevention through speaking engagements like the one in Dallas. “I really believe in posttraumatic growth,” she said.

“The more I learned about suicide, the more I learned about how many people are struggling with suicidal thoughts at any one time,” she said. “I needed to do something, and I think this was my guiding light that pulled me through.”

“It’s my way of saying I’m doing this for you, Dylan. I’m doing this for everyone who died or was hurt by you, and it gives my life meaning and purpose.”