AUSTIN, Texas — This article originally appeared in The Texas Tribune.

Texas lawmakers are changing their tune about how to tackle a growing fentanyl crisis in the state ahead of the next legislative session starting in January.

Earlier this month, Republican Gov. Greg Abbott led the way by coming out in favor of legalizing fentanyl test strips, which help users identify whether the drugs they are planning on taking contain the deadly synthetic opioid. Abbott previously opposed such a policy but said the increase in opioid overdose deaths had brought a “better understanding” that more needs to be done by the state to tackle the problem.

“The message from Abbott that he’s willing to support that is huge because that gives the go-ahead to the House and Senate,” said Katharine Neill Harris, a drug policy fellow at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy. “It signals that if we get this passed, it’s not going to necessarily get vetoed.”

Bills to legalize fentanyl test strips, and other similar programs like syringe exchange services that aim to minimize harm for those addicted to drugs, have been filed in the past, but were mostly authored by Democrats and had little chance of becoming law in a Republican-dominated Legislature. Many tough-on-crime Republicans have opposed such measures, concerned that they enable drug use.

Now, some of the Capitol’s most conservative names — like state Sen. Bob Hall of Edgewood and Rep. Tom Oliverson of Cypress— are taking up the case for legalizing fentanyl test strips. And the issue is getting help from top legislative leaders.

“I believe that recommendations made by the public health committee will receive broad support in our chamber, such as legalizing fentanyl testing strips, encouraging the availability of naloxone and promoting a more centralized and coordinated data collection effort to better inform law enforcement and emergency medical services,” House Speaker Dade Phelan said in a statement.

Abbott also said he wanted to make Narcan, a drug used to reverse opioid overdoses that is generically called naloxone, more readily available across the state. First responders and harm-reduction groups that work with people who use drugs have difficulty supplying Narcan because of its cost — about $125 for a kit with two doses.

Republican and Democratic lawmakers are working together to pass harm-reduction measures. That’s been encouraging for drug policy experts who have been sounding the alarm about the rise of fentanyl in the state for years, but they said the state still needs to do more.

“We are excited about the possibility of legalizing fentanyl testing strips, but that’s one tiny step forward, and we really need to be taking huge strides to get our arms around this crisis,” said Cate Graziani, co-executive director of the Texas Harm Reduction Alliance.

The proposed policy changes come as the opioid crisis continues to batter the country. Nationwide, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that more than 107,000 people died from drug overdoses in 2021, the last available year. Synthetic opioids were responsible for 71,000 of those deaths, and they were largely from fentanyl.

In Texas, the CDC predicts that more than 5,000 people died of drug overdoses between July 2021 and July 2022. Overdose deaths involving fentanyl in the state rose 399%, from 333 people dying in fiscal year 2019 to 1,662 in fiscal year 2021.

The change from Republican leaders in Austin also comes nearly two years into Abbott’s unprecedented border mission, Operation Lone Star, which has cost the state $4 billion for border security and sent thousands of National Guard members and Department of Public Safety troopers to the border with underwhelming results. One of the operation’s main goals is to stop the flow of drugs across the border, but fentanyl deaths have increased in the state in recent years.

“If 50 years of the war on drugs isn’t enough to prove it doesn’t work, then we can look to the past two years,” Graziani said. “Those strategies aren’t working. We need public health strategies, and we need to stop criminalizing paraphernalia so we can focus on the care.”

Sen. Nathan Johnson, D-Dallas, who filed a bill for the new session to decriminalize strips and other technology that can help detect fentanyl, said the state needs to take swift action.

“We have a lot of people dying of accidental drug overdoses as a result of taking drugs that they didn’t know contain fentanyl,” he said. “This affects a lot of people, including college kids, and we, in Texas and nationwide, have suffered devastating overdose losses of life.”

Showing the issue’s bipartisan appeal, Johnson has teamed up with Hall to push the bill through. Similar bills have been filed by Oliverson and Austin Democratic Reps. Sheryl Cole and James Talarico.

“We don’t agree on a whole lot of things, but it does show you that sometimes they’re just the right answers,” Johnson said.

Hall did not respond to a request for comment.

A broader bill around legalizing fentanyl test strips and other drug paraphernalia filed by Dallas Democrat Jasmine Crockett did not get a hearing on the House floor last session. But with more lawmakers having constituents affected by the opioid epidemic, a narrower bill that deals only with fentanyl testing tools, and support from top Republican leaders, the odds for passage of this year’s proposals are much better.

Marc Levin, a criminal justice expert who has worked on legislation in Texas in recent years, said the change in attitude is “noticeable.”

“It’s not just that opioids have had a significant effect on rural areas, which are represented by Republicans generally, but the connection to China and illegal smuggling across the border — those two things have elevated the issue among Republicans,” said Levin, chief policy counsel for the Council on Criminal Justice, a nonpartisan think tank.

Still, he said, it’s beneficial for lawmakers to reevaluate their past positions on policy based on data and new information.

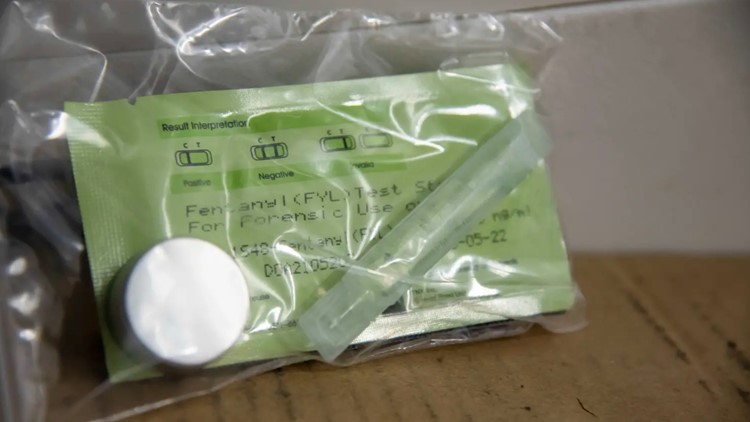

Fentanyl test strips are seen by drug policy experts as an important tool in preventing overdose deaths. Drug users often do not know that the drugs they are taking are laced with fentanyl.

The test strips allow users to safely learn whether the drugs they have bought contain the dangerous drug and head off a potentially dangerous overdose.

Drug policy experts say that providing the test strips to users and giving them a chance to avoid fatal overdoses opens the door to a continuum of care that could help get people off drugs.

“If you’re out on the street and giving them care packages with Narcan and fentanyl testing strips, that’s an engagement with a health care worker that these people may not [otherwise] be getting,” Neill Harris said.

In recent years, states have moved toward legalizing fentanyl test strips, including Republican-dominated ones like Wyoming, Nebraska, South Carolina, Alabama and Tennessee.

Some law enforcement groups, which have long been resistant, are warming to the legalization of fentanyl test strips as a tool in the battle against opioid deaths.

Jennifer Szimanski, public affairs director for the Combined Law Enforcement Associations of Texas, said her group is generally supportive of decriminalizing fentanyl test strips but would have to look at specific legislation.

Others are still expressing some apprehension.

Kevin Lawrence, executive director of the Texas Municipal Police Association, said his group is still considering the idea.

“Our concern is how widespread is it, what kind of controls will there be and what are the repercussions for abuses of this?” he said.

Neill Harris said the reticence toward legalizing test strips is similar to opposition from law enforcement to a 2015 law that allowed people other than doctors to have and deploy naloxone, an opioid-reversing drug. Opponents at the time argued that investing in increased access to naloxone could encourage drug use. That law also granted legal immunity to a person who tried to give the drug to someone they believed to be suffering from an opioid overdose.

Narcan is an intranasal form of that drug, and law enforcement officers are now clamoring for the state to make it more readily available to them. That’s after years of education from experts have taught police across the state how easy the drug is to use, how effective it is in saving lives and the law’s protections for first responders who use it to try to reverse an overdose.

“We need to get Narcan in the hands of more police officers,” Szimanski said. “We’ve had members reach out in the last few months if there’s any way CLEAT can provide Narcan because their administrations are not providing it.”

Another version of naloxone is cheaper, costing between $1 and $25 a unit — but that must be injected, requiring more training.

This year, a federally funded state-run program out of the UT Health San Antonio School of Nursing that provided free Narcan ran out of funds halfway through the year.

The program was also a victim of its own success. So many groups had become dependent on it for free Narcan that it could not fulfill all the requests it received. In 2023, the program, called “More Narcan Please,” is limiting groups to 48 units per order and emphasizing the need to get the lifesaving drug directly into the hands of those most affected.

Graziani with the Texas Harm Reduction Alliance said she wants to see more details about Abbott’s plan for making Narcan more readily available. Some states have prioritized getting the drug in the hands of law enforcement, but some drug policy experts say it is more effective to get Narcan in the hands of drug users, their family members or harm-reduction groups that directly interact with drug users since those are the people most likely to have an interaction with a person experiencing an overdose.

Graziani also said she wants to know more about the state’s plan to disperse the drug equitably to ensure that it gets to rural areas that have less resources to buy Narcan, and to harm reduction groups like hers that have direct contact with users. Having Narcan in schools and universities is also an important part of the battle, she said.

“We would love to see a plan in place that prioritizes community-based distributions,” she said, adding that naloxone needs to be “ubiquitous.”

Abbott is also pushing for stiffer penalties for people who knowingly sell drugs laced with fentanyl.

“I want it to be categorized as murder for someone to knowingly provide a fentanyl-laced pill to someone who ingests it and dies,” he said earlier this year.

Drug policy experts oppose such a move and say it is a continuation of “war on drugs” strategies that have not worked in the past.

“Our drug supply is more deadly now than ever because we continue to double down on those prohibitionists or tough-on-crime policies, and we know that through research, increasing criminal penalties does nothing to decrease drug use,” Graziani said.

Levin said the policy proposal is “well-intentioned” but has problematic unintended consequences.

“The biggest concern that I’ve seen with other states is that while it is intended to go after drug kingpins, most of the people who have been prosecuted have been family members or other people who were there at the time of the overdose,” he said.

Studies have shown that with an increase in “drug-induced homicide” prosecutions in jurisdictions that pass these laws, the rate of overdose deaths actually goes up. In an analysis in Wisconsin, 90% of the people prosecuted on these charges were friends, relatives or low-level drug dealers selling to support their own drug use. In another in New Jersey, 25 of the 32 such prosecutions were friends of the deceased who did not regularly sell drugs.

Experts say lawmakers should instead focus on policies driven by public health research. They say the effort to decriminalize fentanyl test strips should expand beyond that drug to cover other potentially dangerous substances. Drug traffickers are already using other substances to increase the power of street drugs, and legalizing test strips only for fentanyl could leave users prey to other drugs.

“What I would like to see is the legalization of any drug-checking tools or technology that are used for reducing risk,” Neill Harris said.

Experts are also pushing for other changes, like the legalization of syringe exchange programs, which swap out used syringes for new ones to prevent drug users from contracting diseases, and changes to the state’s “overdose Good Samaritan” law, which protects from arrest or prosecution a person who calls for emergency help — but has steep requirements for people to receive that protection.

The Good Samaritan law does not protect people who have felony drug charges on their criminal records or who have called for emergency help in the last 18 months. Both requirements would rule out a large number of drug users or their families.

“We understand that regardless of someone’s history, they need to be able to call [for help],” Graziani said. “It’s punishing the person who might die because someone around them has a [criminal] history.”

Abbott has not indicated support for either of those policy ideas, which makes their passage by the Legislature less likely.

But drug addiction experts say they will continue to push for a more holistic approach to combating the nation’s opioid overdose epidemic in Texas.

“Narcan access and even fentanyl testing strips are steps in the right direction, but we’re going to need more than that to address this,” Neill Harris said. “We sort of need everything. We need to throw the kitchen sink at this.”

The Texas Tribune is a member-supported, nonpartisan newsroom informing and engaging Texans on state politics and policy. Learn more at texastribune.org.

Disclosure: CLEAT, Rice University, the Baker Institute for Public Policy and UT Health San Antonio have been financial supporters of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune’s journalism. Find a complete list of them here.