DALLAS — It’s a neighborhood in Oak Cliff sitting high on a hill overlooking downtown Dallas.

“Everybody that’s anybody lived here,” longtime resident Patricia Cox said. “We had the most prominent doctors and lawyers, and we were self-sufficient.”

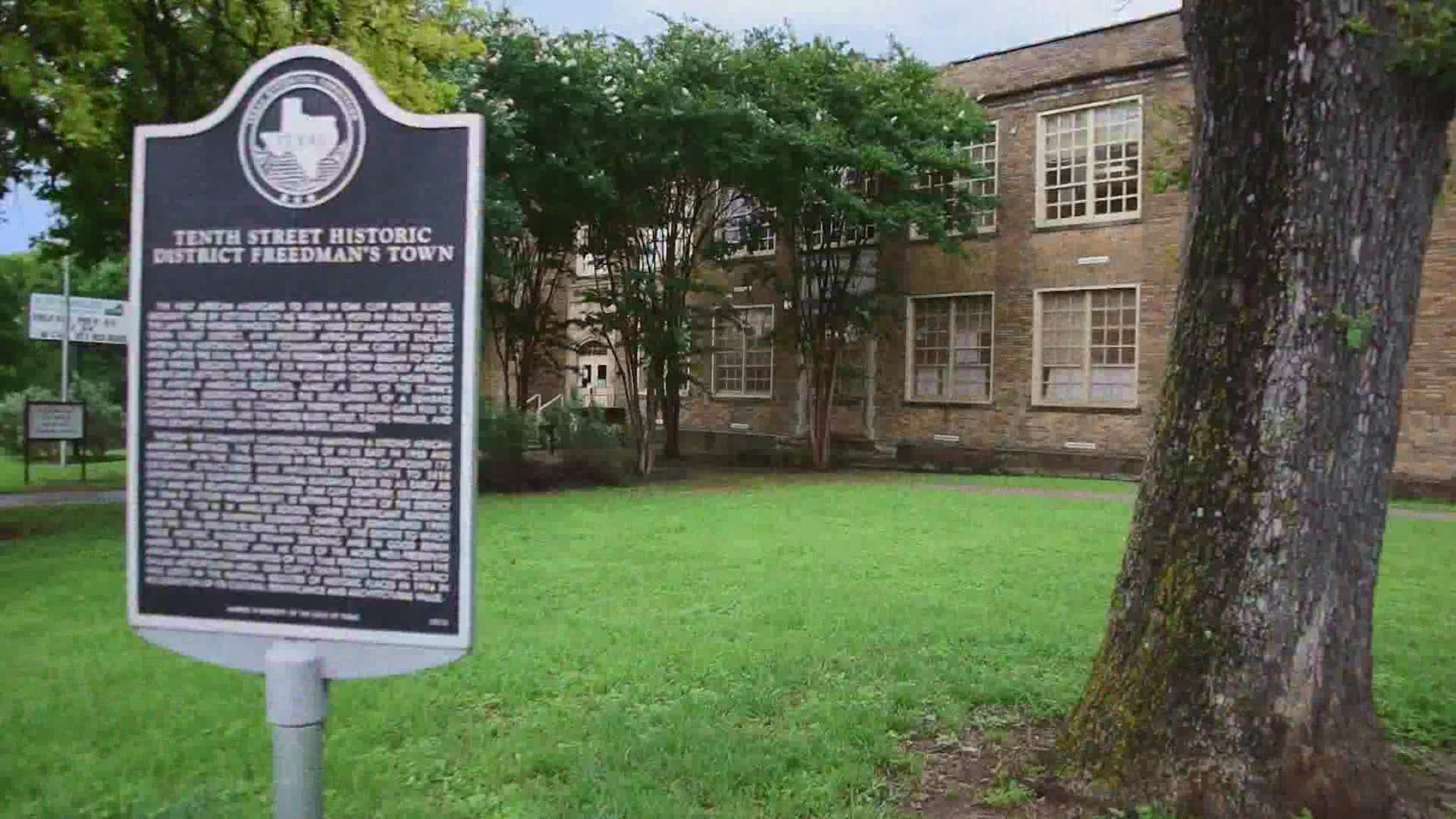

The Tenth Street District is one of the only remaining intact Freedman’s towns in the country. It’s a place where once enslaved African Americans, who were grappling with Jim Crow laws settled. They created their own community at the end of the 19th century following the Civil War.

“We’ve always been a thriving neighborhood until they started like the Pied Piper, opening up other places instead of repairing this one,” added Cox.

The home Cox adores – the community is all part of a family legacy that spans more than seven decades.

“This is my sister Erma, this is my brother,” Cox shared, as she pointed out the images on a white poster board.

The images are a glimpse of the Tenth Street District in its heyday.

Harllee Elementary School was built in 1929 for Black students and is still standing, and so is Greater El Bethel Baptist Church. The church itself has been around since 1886.

The Oak Cliff Cemetery, the oldest public cemetery in Dallas also borders the community.

The history of this area is what the Tenth Street Residential Association is fighting to preserve.

Some witnessing firsthand its deterioration that started in the 1950s with the construction of Interstate 35. Not only did it divide the Tenth Street District from the rest of Oak Cliff, “it broke up our community,” said Cox.

That construction along with integration in the 1960s resulted in the demolition of around 175 original buildings forcing many to relocated.

Now, the community is left searching for answers and people, like Demetria McCain with the Inclusive Communities Project, want to help.

According to the organization's website, its mission is to seek redress for policies and practices that perpetuate the harmful effects of discrimination and segregation, ICP’s Neighborhood Equity and Options (NEO) program addresses the vestiges of racial segregation in neighborhoods without adequate services and facilities.

“There are systemic problems and racial inequities throughout all of Dallas and Texas, and quite frankly the United States,” McCain said. “So, even though the Fair Housing Act was passed in 1968, there are still problems, some of those problems may seem benign but actually the effect of them harm people of color.”

Some of those problems stem from a City of Dallas ordinance passed in 2010.

It set 3,000 square feet as the benchmark for residential structures that could be quickly demolished without seeking alternatives and resources that might save them.

“Because this is a freedmen’s town, recently enslaved Africans didn’t build structures that were 3,000 square feet,” McCain said. “So, that ordinance protects certain other districts, which are predominantly white, don’t protect the Tenth Street District.”

“At this point, this is where we are, we have not had that conversation, but what we are involved in is providing a platform to individual homeowners who have interest in renovating their homes,” said Carolyn King Arnold, who represents the district on city council. “We have provided through council initiatives, some $750,000 to assist those owners in upgrading their structure.”

Realizing there has been a challenge to many of those homeowners who are seeking help from the city because of lack of clear access to a title/deed, King says they have earmarked funds to assist those families.

“Historically, we know that some of the properties were passed down and left to several members of the family, so there’s no clear path of ownership, so we also established some $250,000 to allow those owners to participate in a legal path to clearing those titles because you can’t get the city subsidies unless you have clear title and clear ownership.”

King provides details on how to apply in the video below.

Passage of a resolution in 2019 halted those demolitions, but with the ordinance still on the books, residents worry it is only a temporary fix.

“It’s the same story, the wealthy eating up the poor,” said Cox.

They say the neighborhood has been a target for redevelopment since the mid-90s. Some worry the Southern Gateway project, a five-acre deck park spanning I-35E between Ewing and Marsalis Avenues will further the interest in their community. According to their website, developers say it's a way to address the City of Dallas' north-south divide.

The Tenth Street Residential Association hopes to address rapid growth with what they are calling a neighborhood-led plan that puts current residents at the forefront of future growth.

“We’d like to refurbish the homes, have tours, become self-sufficient again like we always have been,” Cox said. “We are a desert. We don’t even have grocery stores in the neighborhood anymore. I always tell these young people, if you don’t know where you came from, you don’t know where you’re going.”

Shaun Montgomery of the Tenth Street Residential Association provides brief history lesson of the neighborhood.

Credit: Special thanks to the Shaun Montgomery, member of the Tenth Street Residential Association for providing many of the images used in this story.