FORT WORTH, Texas — Mariachi is more than a genre of music. It’s a collection of old stories passed down for generations. While its roots are in Mexico, it thrives today hundreds of miles from the border in homes of students in North Texas.

In the classroom

In recent years, North Side High School in Fort Worth has earned a reputation as one of the state’s most successful mariachi programs. More than 90% of the student body is on free or reduced-price lunches and about 93% of students at the school are Hispanic, according to the Texas Education Agency. Most students in the program are first-generation Americans, but its mariachi has served as a springboard to opportunity.

“A lot of times these kids only have us, you know, sometimes your class may be the only thing they look forward to,” Ramon Nino, the director of the North Side High School mariachi program said. “Our kids enjoy performing. Some of them come to school just because of this mariachi program.”

The story of North Side’s success started when Nino wanted to change an old narrative.

“It was never really our goal to win,” he said. "It was more to just go out there and make a mark for North Texas mariachi because it was so heavily populated by South Texas mariachi groups.”

The team started competing in the state mariachi festival in 2014 before it was run by the UIL.

“We had no idea what we were doing,” Nino said. "We were, you know, picking songs that we thought were going to be good for competition and then seeing some of these big groups that were really well established, and I'm like, ‘man, we have a lot to learn.’”

The team has been quick learners.

Three years later in 2017, they beat a Grammy-nominated student mariachi group for a national title, and every year at the state mariachi festival, they’ve received a first division score, the highest level possible.

“The work ethic, like I said, this is what got me in this program, is nowhere near - it's far beyond what I've seen in other places,” Nino said.

Nino leads the program with the help of associate Director Imelda Martinez. They believe their success starts not in the classroom but at home.

“We get the pride of, ‘this is the music my parents and my grandparents grew up with and listened to and this is what they were singing when they were working in the fields,’” Nino said. “The grandmothers who knew this song and were teaching their kids or singing to their kids. A John Philip Sousa march doesn't do that, you know, for anybody I don't care who you are. It's just completely different.”

At home

Senior Diana Aguado and her sophomore brother Nestor live just a few blocks from the school.

Inside, the walls are decorated with hung crucifixes, pictures of family members, a framed Presidential physical fitness award for Nestor and an old honor roll accomplishment for Diana.

The most noticeable living room items, though, are several speakers and karaoke machines around three to four feet tall.

“We just love singing,” Diana said laughing. “That's what we do…for fun.”

In mariachi, Diana plays violin and Nestor plays guitar and sings, so in their home, playing mariachi songs for hours feels less like practice and more a family pastime.

“It's this feeling that I can't even explain,” Nestor said. “It brings you like so much happiness.”

When they immigrated from Mexico, Diana was 10 years old, Nestor was 8 and the family tradition came with them. Diana’s mom plays guitar, too, and sings along.

“I feel like sometimes we just need a reminder of like of who we are,” Diana said.

Next year, Diana will become the first in her family to attend college, but she almost didn’t finish high school.

During Diana's freshman year, her father, who had moved to Texas before they did to settle down, was diagnosed with prostate cancer and became ill to the point he could hardly walk.

“It was difficult,” Diana said. “My father had always been there for us, and then we had to be there for him.”

The family had to return to Mexico and Diana, who was at the top of her class, and Nestor dropped out of school.

“Medicine here and the treatment, everything is very expensive,” Diana said. “We’re going to move and we are going to do this together as a family, and that's what we did.”

When his condition improved, the family moved back to their home in Fort Worth, but Nestor and Diana had missed a year of school.

“I was talking to the counselor, saying, ‘what can we do because she's so far behind,’” Nino said.

Taking summer classes and doubling up in the fall she caught up on her work, and now, she’ll be attending the college at the top of her list.

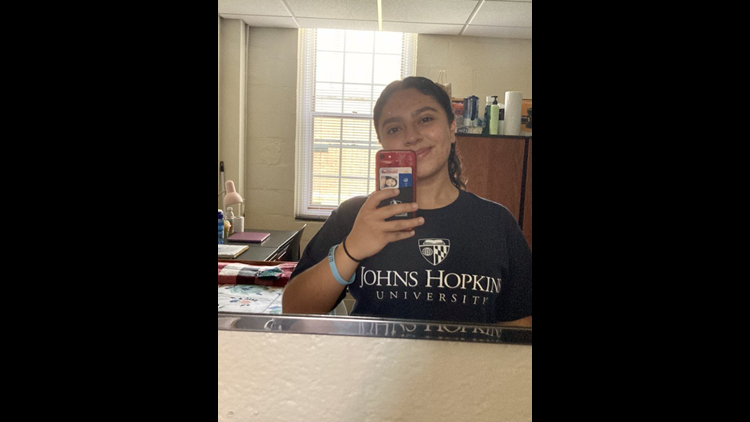

“I checked my status, and then I saw that it said, ‘You're admitted to Johns Hopkins University class of 2025’, and I just I was like, ‘What?’” Diana said laughing. “I couldn't believe it.”

She’ll be headed there on a full scholarship, and her success isn’t unique in the mariachi program.

The other three seniors on varsity mariachi will be Stanford University, University of Notre Dame and TCU. All have full scholarships.

“There's no secret sauce,” Nino said. “It's just the recipe for success is just keep trying till you get it right.”

In the classroom and on the stage that recipe is working.

On stage

This year, the team’s state festival streak of receiving a first division honor continued, and the varsity group did more than just get a top score. Every member of the ensemble received an outstanding performance medal, an achievement just a couple of the 50 bands who entered can boast.

“This is my last year, so it means a lot to me,” Diana said. “When you put in the work and the effort and the dedication, I feel like if you really want to achieve something, you can.”

This past year, everyone suffered adversity, especially students and teachers. With some students in person and others online, practicing mariachi required totally rethinking the way rehearsals were set up. Martinez, the associate director, developed an idea for putting everyone on mute except one student with the slowest internet connection and then playing along.

“We had a kid who was joking, and she was in Mexico last week and she's like, ‘I'm on a tree trying to get service, you know, just joking, but it's true,” Nino said. “Everybody in person would follow that kid, so that way if they were lagging, we were lagging with them.”

But the adversity the team faced wasn’t stronger than their desire to succeed.

“Some had to go to Mexico to take care of things. Some couldn’t be online at all, and then for them to do this,” Nino said holding the state trophy. “To top it all off tomorrow they graduate, and they go out to the real world, so this is an amazing last memory.”

Finale

There is no mariachi program at Johns Hopkins, and Diana wasn’t even been able to visit before she started school there this fall.

She picked it for one reason. Diana wants to study oncology and become a doctor treating cancer patients like her father.

“I have the opportunity to do something for others and so I'm going take it,” she said. “I want to help other people like my dad, and I want to do that for the rest of my life.”

Diana hasn’t told her parents why she picked the school. All she’s allowed herself to admit is that she’d like to be a doctor.

“It’s very tough to find the correct words to tell someone that you’re looking into a career because of them,” Diana recently texted from Johns Hopkins.

She says it’s been tough to be apart from the family she’s never left throughout her life, but she’s seeking out student groups on campus to connect with other Mexican students.

“It is scary and extremely tough, but this is part of the process, it’s part of learning and also part of individual growth,” Diana said.

A home isn’t about walls or borders. It’s where our roots grow.

Mariachi thrives hundreds of miles from the border in North Texas because it’s how to keep home with you no matter how far you go.