ITALY, Texas — At the edge of Italy, Texas on Williams Street, there’s a small, wooden building that has stood for decades. Its exterior is plain and unassuming and it looks very much the same as other houses on the block.

However, its history is extraordinary yet largely untold.

“It is not cataloged anywhere,” said Italy City Councilwoman Elmerine Allen Bell. “We do not have any history that is written in our history books.”

But with the work of Bell, the old building now has a new life to tell its own story and the story of those who entered it.

In 1953, the building was dedicated as the city’s “Colored City Hall.” Italy was a single city with two systems of government, two city halls, and two mayors. When elections were held, there were two ballots.

A town literally divided by race.

“Italy was a typical southern town. It was segregated. There was no electricity in some parts up here on the hill,” said Bell.

"The hill" was the name given to the area where most of Italy’s Black community lived. Over the years, Bell has collected memorabilia and stories from life on the hill. Stories of military service, small businesses, agriculture, and more. They all sit inside the restored building that used to be the Colored City Hall and is now a museum telling a history rarely told before.

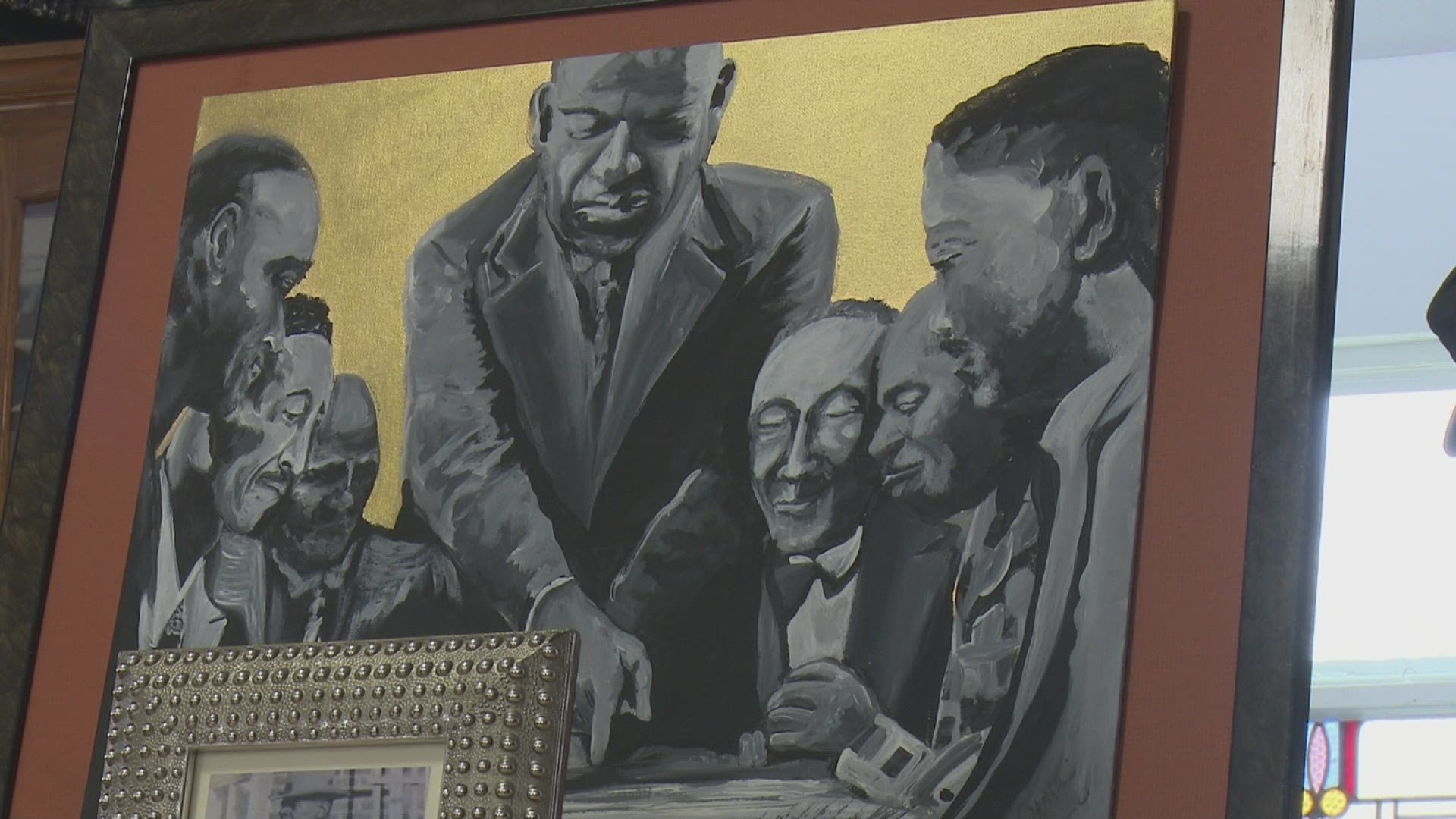

In particular, the museum pays homage to the original city council who served at the Colored City Hall. They originally began meeting in the late 1940s as a way to represent the Black community, leading to the eventual establishment of their own city hall.

Yet, the Colored City Council had no real power and the system kept them from serving on the traditional white City Council where significant decisions about laws, ordinances and city business were made.

Bell said the system initially had support from both sides.

"White folks had a fear of Black folks so they had a reason to support the black government here on the hill," Bell said.

Remnants of the two-government system were still in place even as late as 1975 when a WFAA story preserved in the SMU Jones Film Library examined life on the hill, a life plagued by poverty. In the story, Black residents were interviewed about the history of the Colored City Hall and one woman lamented not being able to have a black man or woman serve as the traditional mayor of Italy.

“In 1947 they said it was a good idea. In 1975, they say it is an embarrassment,” said WFAA reporter Paul Henderson in the story.

But today, the mayor of Italy is Black. Bryant Cockran grew up on the hill and said even he knew little about the stories of the Colored City Hall.

“When I saw that (WFAA story), it was extremely nostalgic for me to see it,” said Cockran. “I literally can’t imagine how it worked.”

A 1951 edition of Ebony Magazine paid a visit to Italy to chronicle the work of the Colored City Council but there is very little record-keeping of their meetings and business. Bell’s work in preserving, restoring and collecting the history helped recently secure a Texas Historical Commission marker for Italy’s Colored City Hall as part of the commission’s "Undertold Stories" program.

Even family members of John Farrow, the first mayor at the Colored City Hall, were amazed during their first time in the new museum.

“The word proud comes to mind. I am overwhelmed because I did not expect to see so much,” said Farrow’s granddaughter Patricia Hall. “This is proof you can make progress, but the word progress means to keep going. To do more. To get better.”

Bell hopes others will be motivated to document their history so it will not be lost. And that history can shape the future.

“I am encouraging everyone to write down what you remember your ancestors told you. We do not need to change anything or sugarcoat it. It is history just the way it happened.”