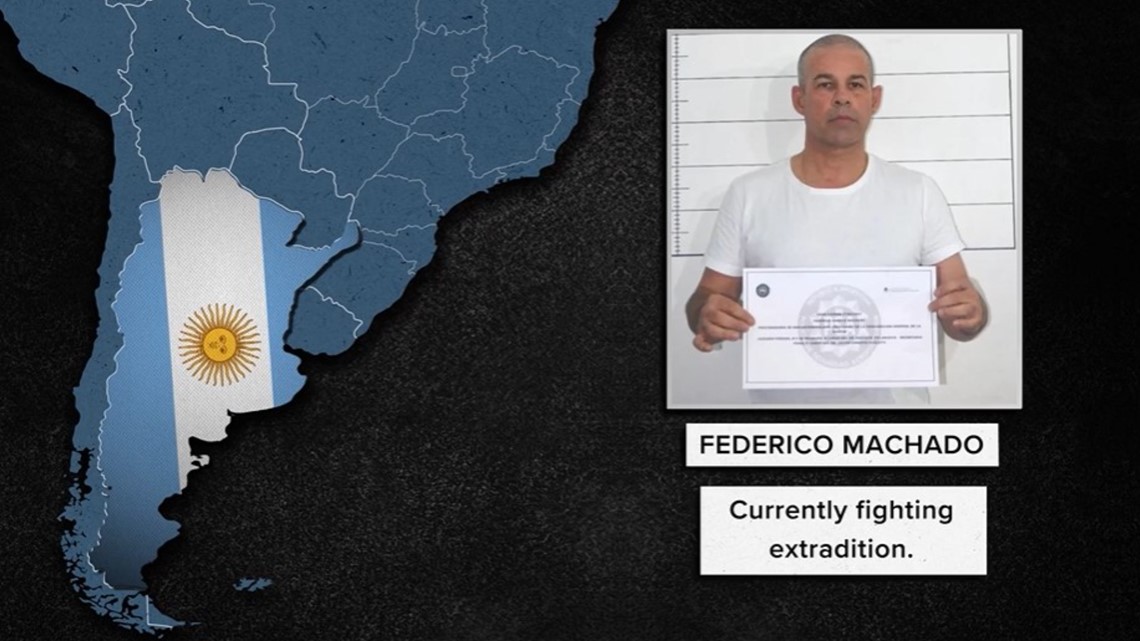

DALLAS — Federico Machado is an international fugitive with a story to tell.

In an interview with WFAA, he says he is not a criminal, but rather the victim of overzealous prosecutors who have accused him of narcotrafficking, money laundering and defrauding investors and lenders of at least $350 million in a scheme to sell airplanes that either didn’t exist or weren’t for sale.

He is fighting extradition to the United States from his native Argentina. He is currently on house arrest awaiting a ruling by that country’s highest court.

“The way they portray me is like you’re talking to El Chapo,” Machado said, referring to the former Mexican drug lord of the Sinaloa Cartel. “The feds have nothing against me on the criminal case, on the drug case. Zero.”

Machado spoke last year to WFAA via Zoom.

“I'm not a saint,” he said. “I made mistakes, but I'm not a narcotrafficker.”

Whether Federico Machado is a narcotrafficker, we don’t know.

What do know is that a series of stories WFAA aired starting in 2019 led to a federal investigation resulting in the indictment of Machado and seven other people. Prosecutors also told WFAA that their counterparts in Colombia attribute a dramatic reduction in the number of narcotrafficking flights to the indictments.

But before we tell you more about Machado and the indictments, let’s go back to where it all started – thousands of miles from Argentina, in Onalaska, an East Texas town nestled along the shores of Lake Livingston.

East Texas origins

WFAA’s investigative team had received a tip that more than a thousand planes were registered to two post office boxes in Onalaska. That’s more planes registered to entire cities such as Seattle, San Antonio, San Diego or New York – and Onalaska doesn’t even have an airport.

And the plane’s owners? Well, they weren’t there.

WFAA’s investigation found Onalaska was the epicenter of a practice that enabled foreigners to anonymously register their aircraft.

Here’s how: Foreign owners can get U.S. registration for their aircraft by transferring the title to a U.S. trust company. In the FAA records database, then, the aircraft would be found in the name of the trust company, not the foreign owner.

U.S.-registered planes carry a coveted “N” tail number.

“An N number, especially if you're operating the airplane in and out of the U.S., draws much less scrutiny,” said Dallas aviation attorney Ladd Sanger.

The trust company registering those planes in Onalaska was Aircraft Guaranty Corp. The company is now based in Oklahoma City.

WFAA’s investigation found that the company’s aircraft repeatedly were found outside of the United States loaded with drugs.

The company’s aircraft were also involved in fatal crashes, and the real owners could not be identified, which the law requires.

After our stories aired, federal prosecutors began digging. They confirmed WFAA’s findings and found new alleged criminal activity.

Expanded federal investigation

The law says trust companies must know who is operating their aircraft, the aircraft’s location, and how it is being used.

The government says that did not happen with Aircraft Guaranty Corp.

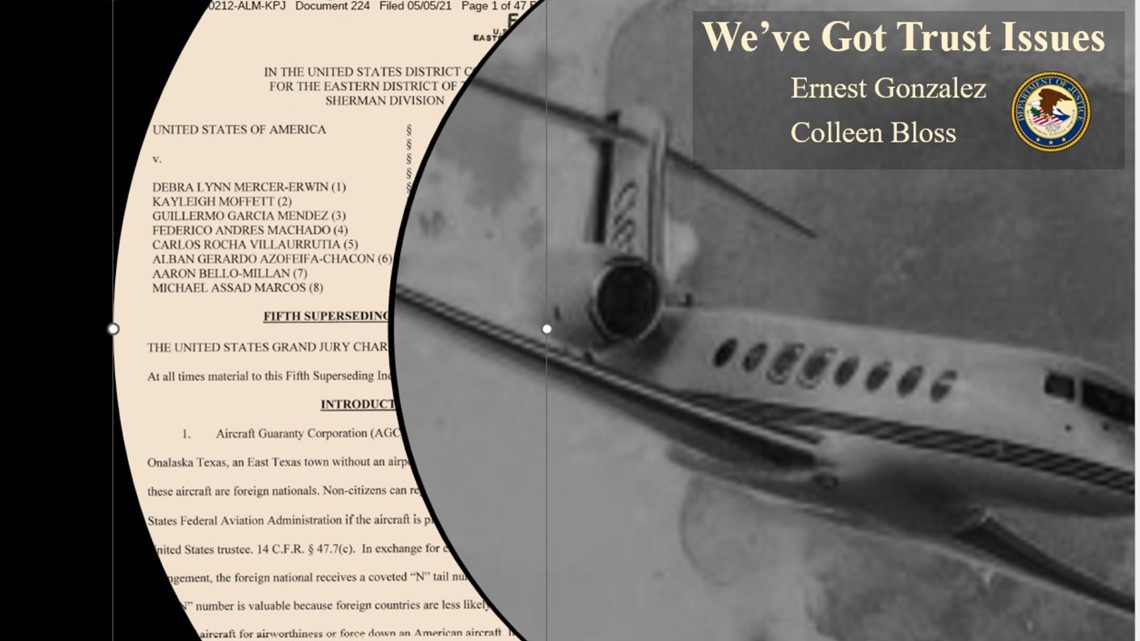

In a 2020 indictment, unsealed in the spring of 2021, prosecutors alleged Aircraft Guaranty’s owner, Debra Mercer-Erwin and her daughter, Kayleigh Moffett, concealed the “true ownership” of aircraft and hid that they had been improperly taken out of the country.

The indictment said that when law enforcement seized aircraft “laden with drugs” in Mexico and Central America, AGC officials tried to distance themselves by either deregistering the aircraft or transferring ownership.

“When you can conceal the true ownership of a plane, you're putting a lot of people in jeopardy,” said Joe Gutheinz, a former FAA special agent.

An unexpected twist

Spurred by WFAA’s investigation, prosecutors kept digging, and found something unexpected:

An alleged scheme involved getting investors to fund the purchase of planes that either didn’t exist or weren’t for sale. Prosecutors allege the fraud totaled at least $350 million.

“They continued to do more plane deals to cover up the previous plane deals, which is your typical Ponzi scheme,” federal prosecutor Ernest Gonzalez said in a 2021 interview. “(Machado) even got individuals to pose as sellers of these planes.”

A battle over those plane deals is still playing out in courts in Oklahoma and Texas.

When WFAA initially asked Machado about the plane deals, he said, he did not want to answer because he didn’t want to incriminate himself.

At other points in the interview, he did answer our questions.

“There’s not a line of old ladies that got cheated, OK. It’s a group of a few people,” Machado said. “They thought they were investing in something. They invest in something else.”

“It can get fixed, if God gave me freedom,” he added. “I will fix it. I will pay them back. This has nothing to do with drugs.”

Machado did not indicate how he would come up with the money to repay the investors.

So where was that investor money going?

Not into buying planes he told us, but rather, his Guatemalan mining operation.

He even gave us a sales pitch.

“It's a beautiful place in the middle of Guatemala with all these Indians,” he said.

Machado says he’s far from a criminal. Rather, he said he is a humanitarian who gave the local indigenous people a better life.

“We were giving jobs to the people,” he said. “They were quite happy.”

Machado told WFAA that he initially cooperated with federal investigators when they first approached him.

“I gave them my phone,” he said. “I gave them my computer. … I told them, ‘Listen if you find something here, just put the handcuffs on me.”’

He also took and passed a polygraph regarding his knowledge of planes being used to smuggle drugs. He provided a copy of it to WFAA.

He said he eventually stopped cooperating and sought refuge in Argentina.

Machado was indicted in 2020, along with Mercer-Erwin, her daughter and other alleged accomplices.

Mercer-Erwin wouldn’t speak to us for this story, but she did talk to us in 2019.

“I would find it very difficult for a criminal or a drug user to place their aircraft in trust, and why would they?” she said. “Why would they want to provide all their personal information, their passport, their corporate documents?”

She discounted the notion that criminals would go through the trouble to place their airplanes in trusts.

“We collect passports on everybody,” she said “We know who our clients are. We have constant communication with our clients.”

Gonzalez told WFAA that federal investigators found that wasn’t true.

“They weren’t doing any vetting at all, and some of these planes were being placed in the hands of drug traffickers, and she knew that,” he said.

Troubled by the Aircraft Guaranty situation, prosecutors created a presentation – entitled “We’ve Got Trust Issues – featuring WFAA’s reporting. Prosecutors presented it to an aviation lawyers group last year in Dallas.

“The Ponzi scheme, the phantom aircraft transactions, the money laundering are all facilitated by the anonymity of the trust system,” said Sanger, who saw the presentation at the aviation law conference at SMU.

In the fallout, federal authorities launched a nationwide review of dozens of trust companies to find out who really owned thousands of aircraft, where they are located and how they are being used.

“That was kind of a wake-up call to the government to say, ‘Look, how widespread is this?’” said David Hernandez, a Washington, D.C.-based aviation attorney. “Once they started receiving the answers, they became overwhelmed, shocked.”

He told WFAA that many of the issues involved planes that had been improperly taken out of the country.

Currently, FAA records show hundreds of planes still registered to Aircraft Guaranty Corp.

But federal prosecutors and aviation attorneys told WFAA no new planes can be put in trust with the company. Also, the hundreds of existing trusts cannot be renewed with Aircraft Guaranty, and any owner wanting to transfer a plane from the company must be interviewed and vetted to make sure they have no drug smuggling links.

Prosecutors also told us that the dramatic reduction in the number of Colombian narcotrafficking is because it's become much harder to get a U.S. registered, N-number plane.

Mercer-Ewin, her daughter and a third defendant are scheduled to be tried in April in federal court in Sherman.

Have a tip? Let us know or email us at investigates@wfaa.com