Special report: 'Dirty Deeds' investigation reveals how house thieves exploit system failures

For the past three years, WFAA’s deed fraud series has highlighted how easy it is to steal someone’s most valuable asset – and attempts by lawmakers to stop it.

Nothing’s sacred for people accused of stealing property.

Not even a church.

Since 2019, WFAA’s “Dirty Deeds” investigation has exposed thieves stealing not only a church, but dozens of homes, a former restaurant – even an entire former Sam’s Club building.

Thieves have learned to take advantage of a real estate transaction system that, for generations, has relied largely on the honor system for recording purchases and sales of property – sometimes worth millions of dollars. WFAA has uncovered a rash of fraud cases where thieves forge sellers' signatures on property deeds, file them with the county clerk and take control of properties they don’t own.

In some cases, they’re forging signatures of people who died years ago.

In fact, WFAA learned Texas ranks No. 2 in the nation for deed fraud cases investigated by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Office of Inspector General.

Chapter 1 'Literally impossible' to stop fraud

Whenever someone buys or sells a property in any county in the Unites States, documents typically must be filed with the county clerk or equivalent government office. But when those documents are filed in Texas, for example, no one routinely checks to see if it’s legit.

Dallas County Clerk John Warren told WFAA that his office accepts more than 400,000 documents annually.

“With the volume that we record, it would be literally impossible to make sure there was no fraudulent intent,” Warren said.

Our investigation found thieves often pick abandoned and neglected properties, figuring the real owners aren’t paying attention.

But not always.

Chapter 2 Church stolen

In 2019, First Christian Church of Lancaster learned something disturbing – they no longer owned their church. Someone named Whitney Foster was the new owner, local tax records showed.

“We thought Dallas County had just lost their mind that they just messed up, that somehow it was some clerical error,” said Rev. Melissa Bitting, the church’s pastor.

Foster was pastor of another house of worship, the True Foundation Non-Denominational Church. The person listed on the deed who granted the transfer was described as the “chairman” of the First Christian Church. But no one associated with First Christian knew the supposed “chairman” listed on the deed.

Bitting and her congregants also discovered another clue – a $10 check Foster wrote in 2019. Bitting says he put it in First Christian’s offering plate.

WFAA reached Foster by phone in 2021 to ask about how he bought an entire church for $10.

“You can acquire a property for $10 with nonprofits,” Foster said. “I was fixing to open up a church there.”

A grand jury indicted Foster on a theft charge for the church. He goes on trial in early 2023.

Chapter 3 No ID required

In Texas, you seldom have to show ID when filing documents with a county clerk’s office to transfer a property’s ownership.

When WFAA first began doing stories on deed fraud, only Harris County could legally require property owners to provide valid photo ID when filing deeds in person.

But the law also had a loophole. It said Harris County could not refuse to file the deed if the person would not show an ID.

After WFAA began highlighting deed fraud cases, two North Texas lawmakers filed legislation during the 2021 legislative session.

One bill, filed by State Rep. Yvonne Davis, D-Dallas, would have allowed county clerks in the state's 254 counties to require property owners filing paperwork transferring property ownership in person to provide a photo ID and allow the clerk to make a copy of it. Counties would be required to reject deed filings from people who don’t have or refuse to provide photo ID.

Another bill, written by State Rep. Craig Goldman, R-Fort Worth, allowed county clerks in counties with populations above 800,000 to require people to show valid photo ID. It didn’t, however, contain a provision that allowed county clerks to refuse to accept documents transferring ownership when someone wouldn’t or couldn’t show ID.

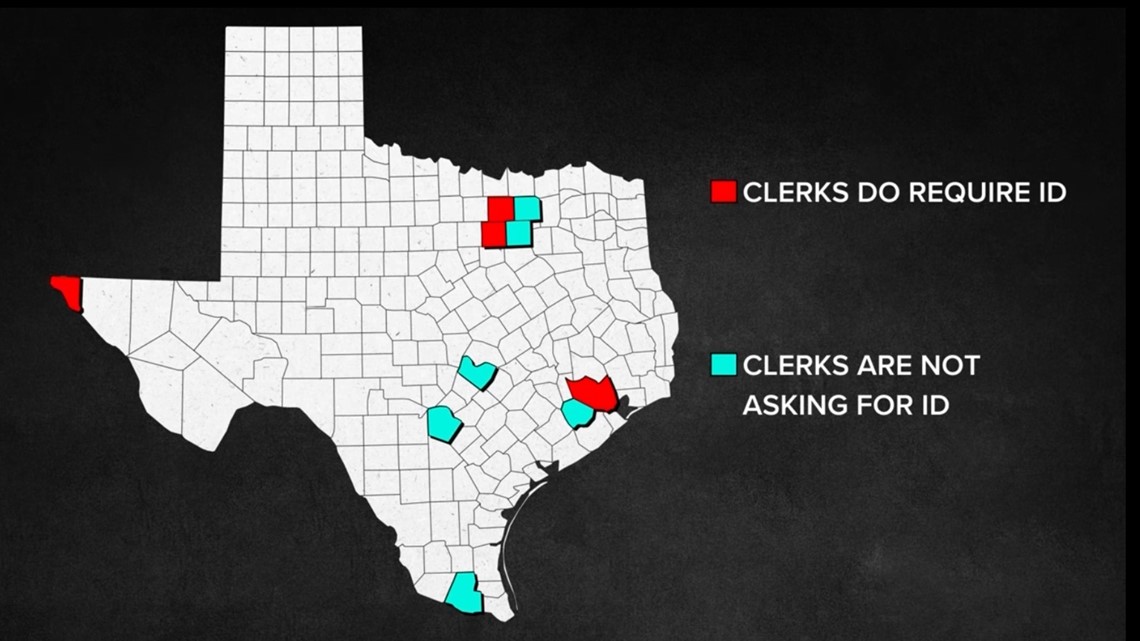

Instead of approving Davis’ stricter bill, the Texas Legislature approved Goldman’s bill, which only covered 10 counties and lacked a provision allowing clerks to reject deeds without photo IDs.

WFAA wanted to know if the counties allowed to ask for IDs were doing it.

Four counties – Harris, Denton, Tarrant and El Paso – told WFAA they require ID when filing in person.

But Dallas County and five others – Travis, Fort Bend, Hildago, Bexar and Collin -- told WFAA that they do not ask for photo IDs. Those counties told WFAA that without a mandatory provision, the law remains unclear. Although clerks may ask for ID, clerks in the six counties said they didn’t believe they had the authority to refuse to file the document. They said that’s because legislators left the confusing line in the law that says a county clerk may not refuse to file a document.

Denton County Clerk Judi Lude told WFAA that she recognizes the inability of her office ultimately to enforce the ID law. But she says counties should at least ask for IDs. “Why not?”

But she said the law likely makes a flat-out ID requirement unenforceable. So, she said the law needs to change. “Why have an unenforceable law?” she told WFAA.

Lawmakers will again be asked to strengthen the ID requirement when the Texas Legislature reconvenes in January.

Chapter 4 Stolen properties from prison

But even an ID requirement may not be enough to stop someone like Arnoldo Ortiz.

In early 2018, Ortiz received a 10-year prison sentence after pleading guilty to more than two dozen counts of theft. Records show Ortiz stole more than 25 properties in North Texas, including single-family homes, a former Sam’s Club and what was once a Burger King.

“He lived in some of the properties,” said a HUD special agent who investigated Ortiz. (WFAA is concealing the agent’s identity because he sometimes does undercover work.)

“He rented numerous properties,” the agent said. “He ended up selling some of the properties.”

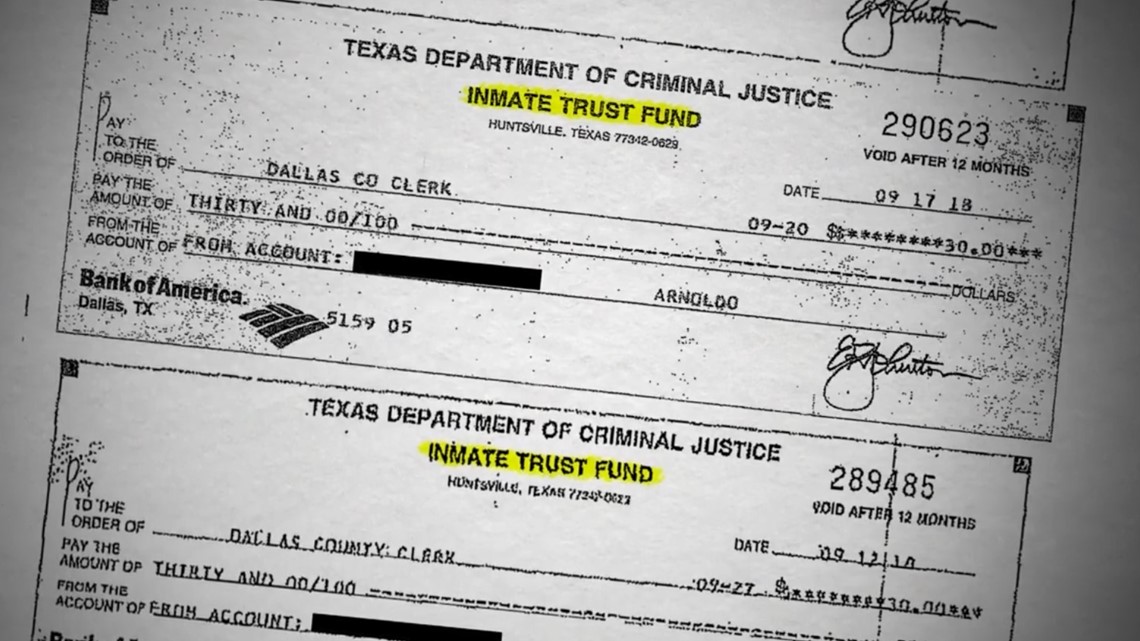

Even after he was already convicted, Ortiz kept filing fraudulent paperwork – from his prison cell.

Within months of pleading guilty, Ortiz filed fake documents attempting to keep control of four homes he had already been convicted of stealing, the agent said.

How did he pay the filing fees? Ortiz mailed checks from his inmate account.

Ortiz told agents of his plans for one of the stolen houses.

“That’s where I’m going to parole when I get out,” Ortiz said.

“Do you think you can just go back and live there?” the agent asked, according to an interrogation video obtained by WFAA.

“Technically, I can,” Ortiz responded.

In 2020, Ortiz pleaded guilty – a second time – to eight felony counts related to property theft.

Chapter 5 Notary publics

So how did Ortiz steal houses from behind bars?

It has to do with people who are called notary publics. Think of them as professional witnesses. The real estate market relies on notaries to watch people sign documents and verify that the people signing their names are who they say they are.

But this system, WFAA has learned, is no match for a determined thief.

“They put a fake signature for the true owner, showing that it's being sold to themselves,” said Phillip Clark, a Dallas County prosecutor who investigates deed fraud. “They get it notarized with a notary public who is in their pocket, or they are their own notary, or they fake the notarization – there all kinds of ways – and then you file it.”

Investigators said Ortiz got unrelated documents notarized in the Dallas County Jail, then took that notary’s stamp and somehow copied it onto forged deed records.

In some instances, the notary is the accused thief.

That happened in the case of real estate investor William Baldridge. In 2017, he notarized documents used to steal a home in Houston that belonged to a deceased Korean War veteran named John Kiel.

One document says a man named David Kiel was the veteran’s son and heir to the home. However, military records for John Keil show he never married and had no children.

WFAA’s Dirty Deeds investigation found Baldridge also managed to get signatures on property deeds from dead people. Those documents then allowed Baldridge’s companies to take over ownership of homes in Dallas and Houston.

A Dallas County grand jury indicted Baldridge in 2021. He’s accused of stealing 20 properties in three counties and selling 17 of them – pocketing more than $1 million.

He remains out on bail, awaiting trial.

Chapter 6 Burden on victims to undo

While the system makes deed fraud easy to do, for the victims it’s much harder to undo.

The law requires victims to go through the civil courts to regain control of their property. Until they do, the real owners can’t sell or use the property as collateral to get a loan.

“These things can take a long time, can be very difficult,” said Clark, the prosecutor. “Usually you need an attorney, which can be expensive.”

In February 2021, after nearly two years of waiting, a judge gave First Christian Church their church property back.

“They put all of the correcting it on the people that have been wronged,” Bitting said. “You have to spend the money, you have to secure a lawyer, you have to take off time to go get the paperwork, that makes no sense.”

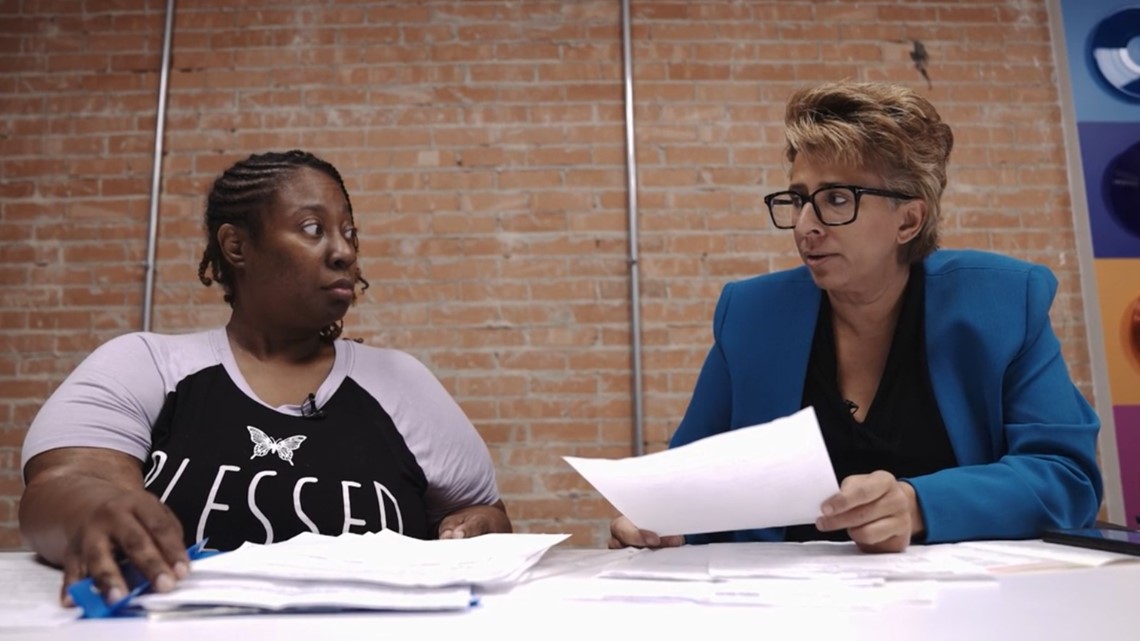

SheBronda Ray is like many deed fraud victims in that she doesn’t have the time or money to get her property back.

Ray was born and grew up in the home her late grandmother bought in 1973 in Dallas. Her grandmother died in 2010, and left a handwritten will giving the home to Ray and her son.

“I tried to get a repair done and they say, ‘It's not in your name,’” Ray said.

She would soon discover that in 2019 someone filed a sworn document with the Dallas County Clerk’s office saying that “Marshall Blaine” was the only child of her late grandmother, and that he was the sole heir to the home.

Almost two weeks later, someone filed another document transferring ownership from “Marshall Blaine” to “Eric Michael Serrano.”

Ray and her family told WFAA that her grandmother had no son named Marshall. The original document naming him the heir also gave the incorrect address for the home.

Chapter 7 WFAA spurs action

Ray filed a report with the Dallas Police Department last summer. But police weren’t actively working the case.

After WFAA pressed the department on what we found, they took another look.

Investigators contacted the notary listed on the sworn documents. He told police that he did not recall notarizing the documents. Detectives could also find no record of a Marshall Blaine.

Investigators also found another property that had been fraudulently transferred to Serrano. Police told WFAA that detectives now believe the theft of SheBronda’s family home may be part of a larger scheme.

So, who is Eric Serrano?

WFAA discovered that he’s a convicted thief in prison for stealing a house in Tarrant County. He is set for release in February.

Back in 2019, investigators with the Tarrant County District Attorney’s Office detained him at the county clerk’s office where he was trying to file another fraudulent deed.

Serrano told investigators that he was just doing what someone else told him to do.

“They told me it was all legit,” Serrano said.

Serrano told detectives that he was involved in the deed-filing scheme so he could make money. He told them he was not the ringleader.

“It was some guy I really don’t know,” he said. He claimed the person had asked him to use his name on deed records.

Serrano did not mention in his interview with investigators that there were other homes in Dallas County connected to the scheme.

He remains in prison. But on paper, he still owns SheBronda’s family home. She currently lives in the home and making repairs.

“It crossed my mind that Eric Serrano may try to say: ‘Hey, this is my house, you need to start paying me rent’” Ray said. “But we have plenty of documented proof that he obtained the house illegally.”

Neither she nor her family have the money to undo the legal tangle confronting them.

Chapter 8 'Good Deed Act'

U.S. Rep. Emanuel Cleaver, D-Mo., filed the “Good Deed Act” after seeing repeated cases of deed fraud in Kansas City. Cleaver, born in North Texas, has reviewed the WFAA Dirty Deed series and said he believes the stories could play a role in motivating lawmakers to act.

“Right now, the people whose property has been stolen, they are the ones who must go out and pay money to get what they own,” Cleaver told WFAA.

His legislation would set aside $10 million to help victims of deed fraud anywhere in the country. To get funding, states would be required to pass laws making it harder to steal property.

The proposed Good Deed Act also would require the FBI to create a crime category to track deed fraud. Cleaver said he is hoping for bipartisan support.

“These people don't go and look at a house and say, ‘It looks like a Republican house. I think I'll leave that one alone,’” Cleaver said. “In a land where we put so much emphasis on owning a home, owning your own property, people can steal it so easily. …Any city that believes it's not taking place is just simply not paying attention.”

Resources

- Those that believe they have been a victim of deed fraud can contact HUD’s OIG Hotline at 1-800-347-3735.

- Dallas County clerk has created forms and instructions to help people who are trying to reclaim property stolen through deed fraud. The forms can be found here on the clerk’s site.

- Have you been the victim of deed fraud? Contact News 8 investigates here.