DALLAS — WFAA-TV has obtained video of what went on in at least one North Texas clinic with a doctor who, prosecutors said put money over his oath to do no harm.

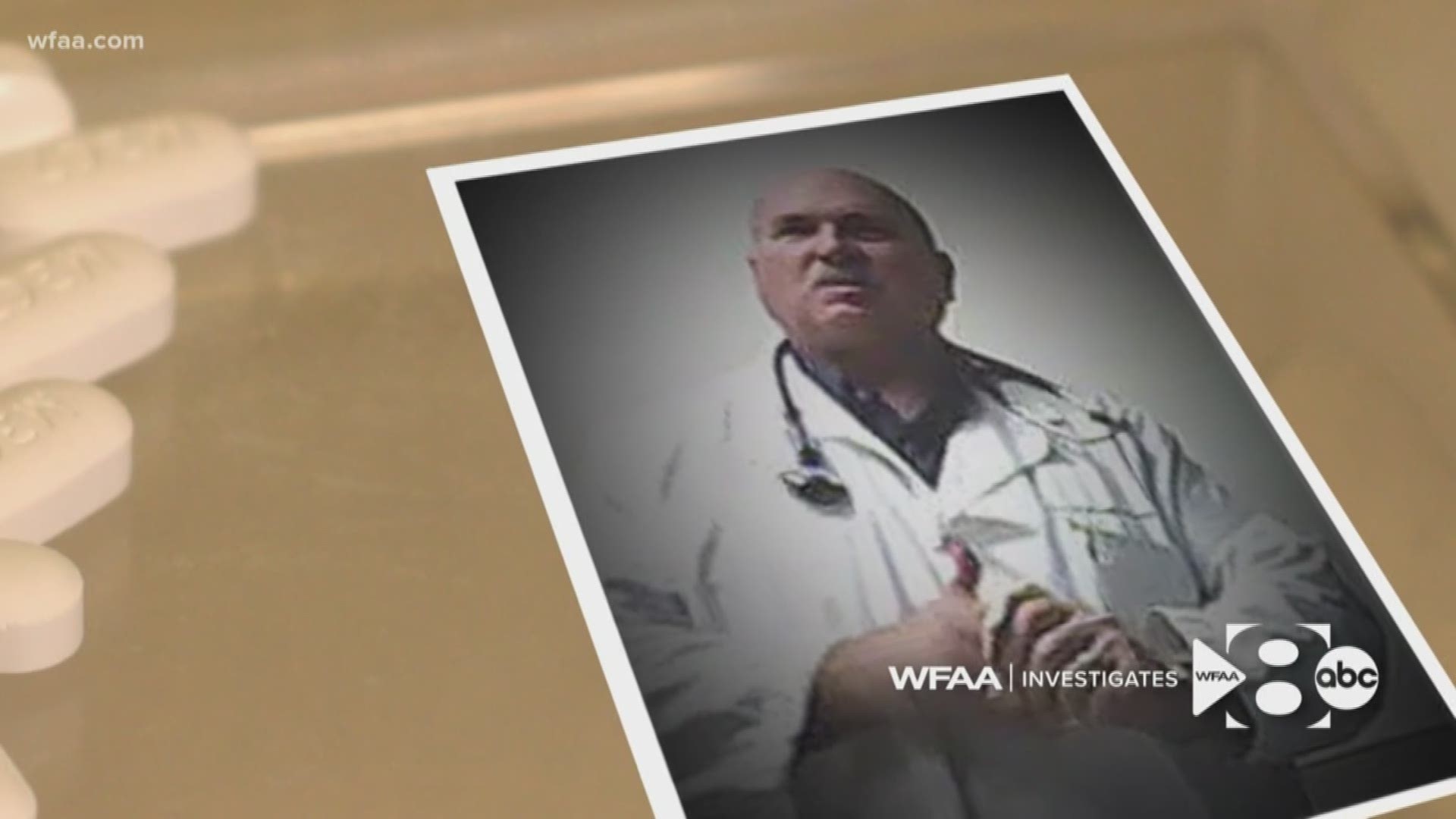

The undercover videos were made during a Federal Drug Enforcement Administration investigation into the medical practice of Dr. Tad Taylor.

Prosecutors argued and a federal jury in 2018 found that Taylor was guilty of trafficking painkillers from Taylor Texas Medicine, his medical clinic in Richardson.

The DEA videos shown at his 2018 trial were actually made during a 2011 undercover operation but did not become available to the public until Taylor was sentenced to prison in May.

The videos show Taylor’s waiting room was always packed full of people waiting to get high-powered painkiller prescriptions from the doctor.

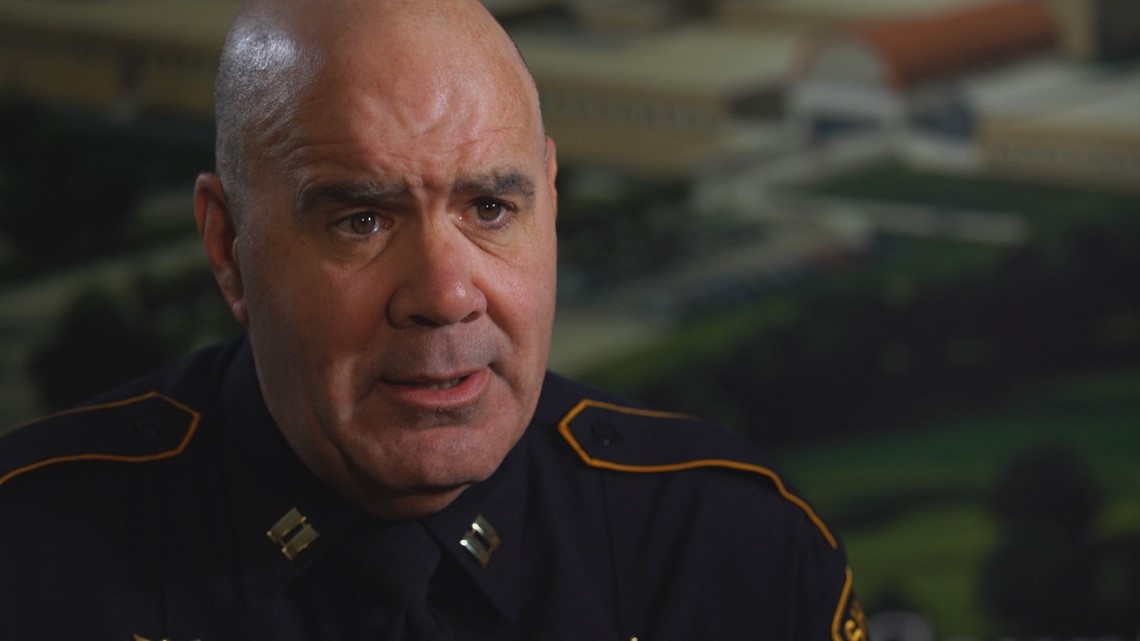

“I went in there believing it would not be nearly this easy,” said Nick Bristow, who back then was a DeSoto police Officer who went in undercover as a patient on special assignment for the DEA. “I gave him every opportunity not to do what he was alleged to be doing.”

For Bristow, now a captain with the Collin County Sheriff’s Office, it was an eye-opening experience.

“I didn’t realize how bad the epidemic was when I started,” Bristow told News 8. “They’re handing out these prescriptions like candy.”

DEA priority

Bristow worked closely with Susannah Herkert, a DEA investigator.

Herkert and her former partner pioneered the DEA’s approach to successfully identifying and taking down pill mill operations in Los Angeles. She then moved onto North Texas where for seven years investigations she put some of North Texas’ most prolific pill mill doctors, including Taylor, behind bars.

She now heads the recently created Diversion Specialized Training Unit at the DEA training center in Quantico, VA. Her job is to train other DEA investigators and police officers across the country how to conduct investigations of suspected pill mills and to build cases that can be successfully prosecuted.

“The evidence required on these cases is significant and the time involved is significant,” Herkert said.

“We’re not going after the doctors who might make a mistake on one day,” Herkert said.

She said the videos created in the Taylor case serve as a prime example of how undercover operations can help take down a pill mill.

“We wanted to make sure that it is clear that any person, not just a medical professional, could watch those videos and say what this doctor is doing is clearly wrong,” she said. The idea was to make it clear that Taylor “wasn’t just having a bad day. This was a consistent pattern of behavior.”

Undercover videos

On the videos, Bristow poses as a trucker. He looked the part, dressed in jeans with a scruffy beard.

“I’ve been using hydrocodone for a while,” Bristow told the doctor during his first visit.

“Did you have an injury?” Taylor asks.

“No, I mean it’s just, it kind of makes me feel a little better and gets me through the day,” Bristow responds.

The doctor continues asking Bristow if he’s had any injuries. Bristow makes it clear he’ll say anything the doctor wants just to get the drugs.

Taylor says he needs the information for Bristow’s medical charts. He needs to document it in case regulators come to audit him.

“I had a bike wreck five years ago,” Bristow finally says.

“Awesome,” the doctor says, giving Bristow a thumbs up.

Bristow asks how many hydrocodone pills he can give him. Taylor tells him he can write him a one-month prescription for 90 pills.

“Start with that and we’ll go from there,” Bristow says.

The doctor’s physical examination is cursory. He asks if Bristow has back pain to which Bristow asks, “Where do you want it to hurt?”

The doctor tells him, “You tell me. I want to be good for you. I don’t want to make you a drug addict.”

“Thigh, I guess,” Bristow says.

“My goal is to help, not harm,” Taylor says. “But if you’re in pain, we’ll treat it.”

Herkert said the videos show that Taylor knew what he was doing and that he was “trying to cover his tracks.” She cites his repeated comments about having to document in the patient files in case the clinic is audited.

“He was saying things that he clearly knew that this person – this undercover agent – did not need the controlled substances or was potentially abusing them, and yet he wrote the prescriptions anyway,” Herkert told News 8.

Bristow said he was struck by the fact that Taylors’ clinics operated on an all-cash basis. During visits, he said he spoke to other patients in the waiting room. He said they coached him on what he needed to say to the doctor.

'I know you gotta write something in there.'

The next month, Bristow went back to the doctor’s office. The doctor asks how his back is doing.

“Always good. Always good,” Bristow replies.

Taylor wants to know how his leg is doing.

“It’s always good,” Bristow says.

The doctor wants to know which one he was supposedly treating.

“Left, wasn’t it?” Bristow says. “Right, left?”

Bristow told News 8 he could not recall what he’d previously said in the prior visit.

“I know you gotta write something in there,” Bristow tells the doctor.

At the end of the visit, the doctor writes another prescription for high-powered, addictive painkillers.

On Bristow’s third and final visit, Taylor and his nurse both questioned why hydrocodone isn’t showing up in Bristow’s urine during testing.

Bristow tells the nurse that he took a pill the day before. He tells the doctor another story, that he ran out a week earlier.

The doctor doesn’t question the discrepancy. Instead, he explains to that it’s best for the drugs to show up in his urine in case the doctor’s office gets audited.

“That tells him I’m not using it right, so what am I doing with it?” Bristow told News 8. “Am I selling it?"

The videos show what happens next.

“Do you want me to give you more?” Taylor asks.

“Yes,” Bristow responds. “… How many can you give me?”

The doctor says he can prescribe another 90 Xanax pills and 120 Lortab (hydrocodone) pills. He’d given him a prescription for 60 Xanax pills and 90 Lortab pills on the prior two visits.

“Let’s do that,” Bristow says. “That should work.”

Taylor at this point has already come under scrutiny from the Texas Medical Board for his prescribing practices. Taylor license to practice medicine was suspended in 2014. He lost it in 2016.

'It's money. It's greed.'

“It’s money. It’s greed,” Bristow said. “They’re really no different than any other drug dealer.”

Herkert believes the investigations she led had a significant impact on fighting the opioid epidemic in North Texas. Two of the doctors targeted by her investigations – Randall Wade and Howard Diamond -- were top prescribers of the powerfully addictive drugs.

Wade, a former McKinney doctor linked to eight deaths, was Texas’ top prescriber of hydrocodone in 2015, according to court testimony. He is serving 10 years in prison.

Diamond, whom authorities blamed for seven deaths, ran a booming pain management practice with clinics in Sherman, Sulphur Springs and Paris, Texas.

Patients came from all over North and East Texas, as well as Oklahoma, traveled to see Diamond. In 2014, he ranked No. 2 in Texas among all specialties of doctors for prescriptions for both morphine and oxycodone, according to ProPublica’s analysis of Medicare data. He is serving 20 years.

Taylor was not linked in court documents to any deaths. He is also serving 20 years.

“These are people that are highly educated who know better who know how dangerous these drugs are and how it can turn a community upside down,” Herkert said.

Even now, she still maintains contact with many of the families who have lost loved ones in the opioid epidemic.

“It’s heart wrenching to hear their stories and it’s something that’s also a motivating factor to continue to do these cases,” Herkert said. “You can’t bring their loved ones back, but hopefully you can prevent another family from experiencing the same loss.”

Email investigates@wfaa.com

More on WFAA:

- Charges filed against 58 people in statewide health care fraud crackdown

- 'I am awesome': How a millennial built a fentanyl empire

- Potential alternative to opioids discovered in Denton lab

- Fort Worth paramedics respond to about 3 opioid overdoses a day

- Experimental brain implants studied as drug addiction treatment