FORT WORTH, Texas — Inside her Tarrant County Jail cell, Georgia Baldwin ranted she was a “worldwide wanted hostage.” She played in her feces and often talked to herself.

Baldwin claimed a therapist wanted to assassinate her. She slept on the floor, refused to shower and wouldn’t wear clothes.

On the morning of the 52-year-old’s death, Baldwin had been locked up for five months. Jailers found her lying on the floor unresponsive in her cell, shredded papers strewn all over the room.

An autopsy would soon find the mother of three died of “severe hypernatremia” – a condition generally caused by not drinking enough water.

But Baldwin wasn’t the only Tarrant County prisoner to die from thirst. WFAA found two other cases – both involving prisoners with documented mental illnesses – who died from dehydration in the jail.

“If it's one, it's an outlier, two might be a coincidence, but when you have three, it's a pattern and practice,” said Krish Gundu, who heads the Texas Jail Project, a nonprofit that monitors Texas jails.

In a deposition in an ongoing lawsuit, Chief Deputy Charles Eckert testified that “all three inmates had 24/7 access to water .., so it's not a concern as long as we provide water to them.”

Eckert also spoke to WFAA earlier this year.

“The Sheriff's Department can't hold people down and force water into their mouth, they have to make the conscious choice to walk over to the sink and drink water,” he said.

Tarrant County contracts with My Health My Resources of Tarrant County, or MHMR, to provide mental health services in the jail. In depositions, their employees testified that they rely on jailers to let them know if a prisoner isn’t drinking water.

Depositions also revealed that jailers aren’t trained to recognize signs of dehydration and don’t monitor water consumption of mentally ill prisoners.

MHMR officials referred comment to the county.

“The jail might ask, ‘should a jail really be held responsible to ensure that somebody’s drinking water?” said her family’s attorney, Dean Malone. “My answer to that is if you’ve chosen to incarcerate instead of get help for a severely mentally ill person, then yes, that's your obligation.”

Experts say jails should monitor water intake just as would occur in a psychiatric hospital.

“Simply providing water in a cell is not adequate when you have somebody with serious mental illness,” said psychiatrist Eric Reinhart. “If somebody has a serious mental illness, ... a very common symptom is fear of contamination, and specifically fear of being poisoned by food or liquids.”

Abdullahi Mohamed

The first of those deaths in the Tarrant County Jail came in the summer of 2020.

On June 16 of that year, jailers booked Abdullahi Mohamed into the county jail on an aggravated assault charge after court records show he threatened a relative with a knife.

Records show he was bipolar, manic and had previously been to a state hospital.

Nine days later, the jail put him on a food log because he hadn’t been eating. About twelve hours later, a jail sergeant checked on him and saw his uneaten food tray. Mohamed lied nude on a mattress on the floor.

“I tried talking to him to see if he would eat but he just turned away,” the sergeant wrote in his statement obtained by WFAA.

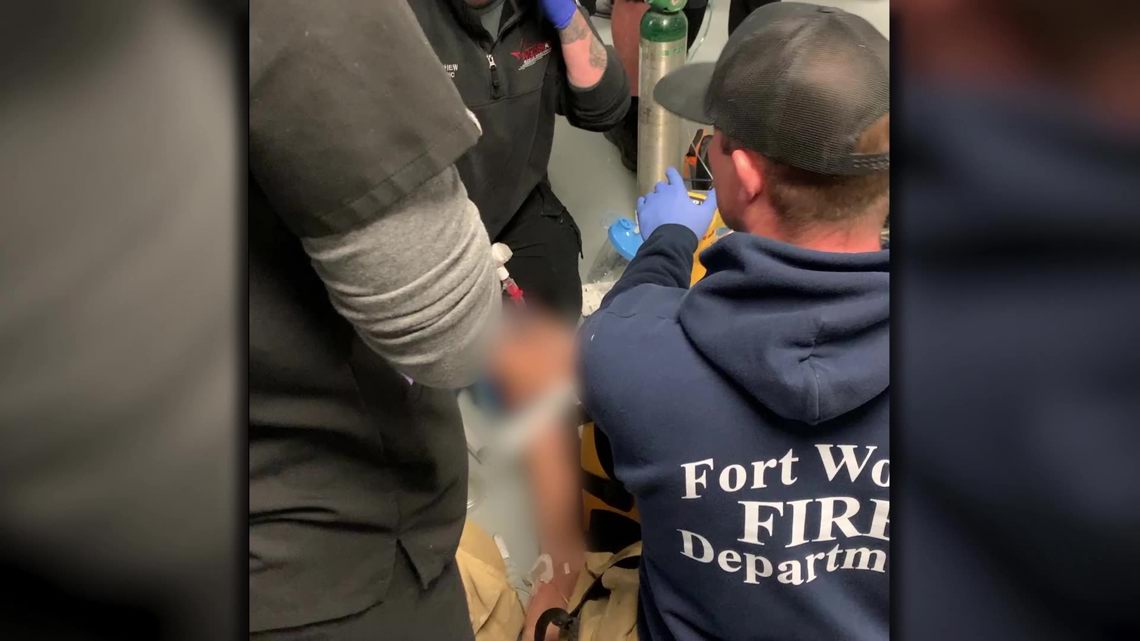

As jailers took him in a wheelchair to medical for evaluation, he urinated on himself and stopped breathing. He died an hour later at JPS.

A Texas Rangers investigation found no wrongdoing by the jailers.

Texas Ranger Trace McDonald led the investigation and now works for the Tarrant County Sheriff’s Department. In his findings, he wrote, “because inmates always have access to water inside their cells through a water fountain toilet, there is no data collected on how much water Mohamed had consumed.”

Georgia Baldwin

Months after Mohamed died, jailers booked Georgia Baldwin into the county jail.

The mother of three adult sons, Baldwin worked as a hairdresser before the downward spiral of mental illness took hold.

“Nothing she would say would make sense,” said one of her sons, Jonathan Mattix. “She lived in a completely different world.”

He says he and his brothers tried their best to help their mother, but to no avail.

It was threatening phone calls Baldwin made to a stranger that got her in legal trouble. That stranger was an Arlington police spokesman.

“Hi, it’s Georgia Baldwin,” she said on one of the calls obtained by WFAA.

“I want you dead like no other,” she said on another.

She ranted about an infamous kidnapping murder case and claimed she knew the identity of the killer.

“Die. Die,” she ranted in a profanity-laced call.

Those calls led to her arrest on a felony terroristic threat charge in April 2021.

“I was always waiting for a phone call from her, saying that she got help,” her son said.

That call never came.

Paranoid and delusional, records show Georgia refused mental health care and wouldn’t take medications. She accused one of her jailers of trying to kill the president.

In June 2021, a psychiatric exam found she wasn’t competent to stand trial. A doctor noted that Baldwin should be “closely monitored as to the effects of her mental state to her functioning.”

“Her symptoms are likely to deteriorate if no intervention is initiated,” the doctor wrote, according to the family’s lawsuit.

A judge ordered that she be sent to a state mental health hospital, but the wait times for a state hospital bed are anywhere from 200 days to almost a year-and-a-half.

So, Georgia remained alone in a cell with her delusions.

“It was apparent to everyone involved in her arrest and incarceration, that she was out of touch with reality,” Malone said.

At about 8 a.m. on Sept. 14, 2021, a mental health worker saw her and didn’t think Baldwin seemed herself. The worker testified in a deposition that she told a jailer she thought Baldwin would “benefit from seeing medical.”

Malone says there’s no evidence that occurred before jailers found Baldwin lying on the floor unresponsive in her cell two hours later, with shredded papers strewn all over the room. Doctors pronounced her dead an hour later at John Peter Smith Hospital.

“Georgia couldn't pick up the phone and say, ‘Hey, I need some counseling,’ or ‘Hey, can you get me a psychiatrist so perhaps I can get some medication,’” Malone said. “She can’t say, ‘hey, I'd really like to be transferred to an appropriate mental health facility or get better treatment.’ She didn't have those options. Tarrant County had to do it.”

In a court filing, the county argued the lawsuit filed by Baldwin’s sons should be dismissed because she “expressly refused medical and mental health care” and signed a “correctional health treatment refusal form” waiver.

“Plaintiffs should not be permitted to bring suit against the County for any consequences of Baldwin having refused medical/mental health care,” the county’s filing said.

Edgar Villatoro Alvarez

In December 2021, jailers booked Edgar Villatoro Alvarez into the county jail on DWI and other charges. Records show he’d been hospitalized a month earlier for a bipolar episode.

Mental health workers repeatedly noted his “strange behavior” that included taking his clothes off and speaking irrationally. One mental health worker noted that during one visit he was “naked, upset and not cooperative.” Another noted a week later that he “presents bizarrely with inappropriate affect ...and (an) illogical thought process.”

The medical examiner noted in his autopsy, “[t]he decedent was reported to have recently ceased eating, drinking and taking his medications for her the last several days.”

On the day he died in February 2022, jailers grew concerned that something wasn’t right with him. One would later write in a statement that he appeared to be “deteriorating and his behavior was off compared to his usual temperament.” Jailers would soon find him not moving in his cell.

Based on the depositions, it appears the county has made no changes since the deaths of Mohamed, Baldwin and Villatoro-Alvarez.

“It sounds like the response of the people at Tarrant County Jail is to expect the people in their custody to behave as they themselves would,” Reinhart said.

Jonathan Mattix, Baldwin’s son, kept the tools of her hairdressing trade. They are a reminder of better times.

“It's tough thinking about what happened her in that jail cell,” he said. “I can only imagine what was going through her mind.”