Broken Trust | The scandalous story behind one tiny Texas town's surprising number of planes

Prosecutors say WFAA's investigation into Onalaska, Texas, led to criminal indictments resulting in a major reduction in Central American drug trafficking flights.

More than four years ago, we began with a question: Why were more than a thousand planes registered in Onalaska, a tiny East Texas town nestled along the shores of Lake Livingston?

In 2019, we found that there were more planes registered to two post office boxes in tiny Onalaska than in big cities, such as Seattle, San Antonio, San Diego or New York City.

Onalaska, we also discovered, doesn’t even have an airport.

“Onalaska is a very small town,” Zachary Davies, a lifelong resident and realtor, told us back then. “It’s a very quiet, little town. There’s not a lot to do.”

Our initial February 2019 story spawned a federal investigation, disrupted drug smuggling efforts that started thousands of miles away, resulted in the discovery of a massive scheme involving fake plane deals and shook up the entire aircraft trust industry.

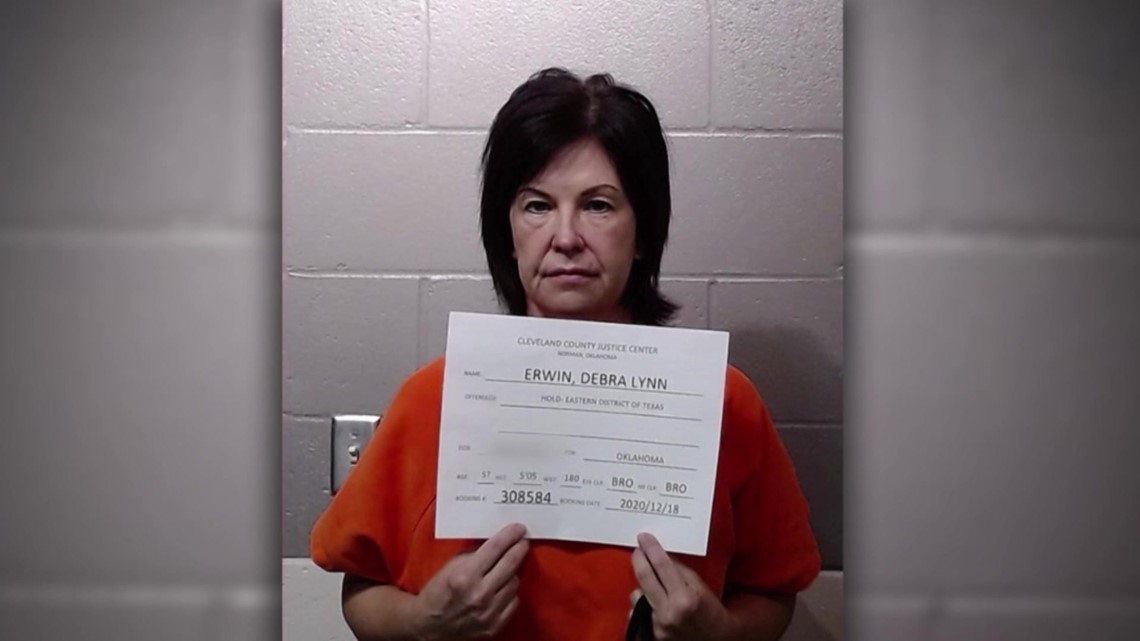

The federal trial that followed resulted in a well-known Oklahoma City businesswoman’s conviction on drug smuggling charges that could put her in prison for the rest of her life.

What WFAA found was that Onalaska was the epicenter of a legal loophole that allowed foreigners to anonymously register their planes.

But how?

Our investigation revealed that the FAA allows foreign nationals to gain U.S. registration for their aircraft by transferring ownership to a trust company.

In other words, a check of Federal Aviation Administration records on these planes would show aircraft registered in the name of the trust company, in effect helping to shield the identity of the foreign owner.

Having an aircraft registered in the U.S. also allows the plane to carry an “N” number on its tail -- a designation that gives the plane certain advantages.

“If you’re operating the airplane in and out of the US, it draws much less scrutiny [with that marking],” said Ladd Sanger, an aviation attorney.

Joe Guthienz, a former FAA investigator and attorney, told WFAA that “there's a sense of confidence that ‘Gee, the Americans must have approved what's going on here. It's got the stamp of approval of the United States of America.’”

Chapter 1 Following the trail

WFAA wanted to know who owned all those planes in Onalaska.

Records showed they were listed to Aircraft Guaranty Corp, a company that used to be based in Onalaska.

Debra Lynn Mercer-Erwin owns that trust company. She bought it in 2014. The company then moved its operations to Oklahoma City.

So we went there.

“We must know who our clients are,” Mercer-Erwin said in a 2019 interview. “We collect passports, all of their passports, their addresses, where they're going to keep the planes. We stay in contact with them throughout our service with them.”

Mercer-Erwin told WFAA that it would be “very difficult for a criminal or a drug user to place their aircraft in trust. And why would they? Why would they want to provide all their personal information, their passports, their corporate documents to place an aircraft in trust?”

Criminals, however, did appear to be taking advantage of the anonymity of the trust system.

In court records, WFAA found two Aircraft Guaranty planes cited in a 2012 federal drug smuggling investigation. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration seized an airplane registered to the trust company in 2016 and opened a criminal case. Through not charged in the money laundering and drug trafficking conspiracy, the real owner of that plane – a Mexican national – paid more than half a million dollars to get it back from the U.S. government.

Also of note: In 2008, a plane crashed into a home in Caracas, Venezuela, killing seven people. The pilot was a twice-convicted drug smuggler. The plane was registered in the United States to Aircraft Guaranty Corp.

The company never identified the real owner.

“There's a fundamental problem,” Gutheinz said. “Under the auspices of the trust you can conceal the ownership of planes, details about the planes, details about who flies the planes.”

There's more: In 2013, a helicopter registered to Aircraft Guaranty crashed into a golf course in Mexico.

“I was never able to find out the actual person who was responsible for that helicopter accident,” said attorney Ladd Sanger, who represented the families of three of the five people killed in the crash.

He says he contacted Aircraft Guaranty, but got nowhere.

“It is a classic case of ostrich head in the sand,” Sanger said. “They don’t ask the questions because they don’t want to know the answers.”

In a post-9/11 America, Sanger and Gutheinz question why a loophole in the law still exists that lets foreigners hide their ownership of airplanes in so-called trusts – like the ones used by Aircraft Guaranty.

“If you're a terrorist and you have a way of concealing your secret ownership of a plane in the United States, you're going to do it,” Gutheinz said.

Federal studies back up concerns that ownership may be disguised. A 2013 audit found planes registered through trusts “lacked key information” about the true ownership of the planes. The review found major trust companies “could not or would not provide the information on the aircraft they own.”

Aircraft Guaranty was one of the major trust companies cited in the 2013 audit.

Chapter 2 WFAA investigation prompts inquiry

After our investigation revealed the loopholes, federal authorities started asking questions, too.

Investigators wanted to know: Where were the rest of all those Onalaska planes? Who was operating them?

In April 2019, the government demanded that Aircraft Guaranty owner Mercer-Erwin produce “information on all aircraft... currently being operated overseas.”

The law says trust companies are required to know who is operating their aircraft, where their planes are located and how they are being used.

Officials say that didn’t happen with Aircraft Guaranty Corp. They say Mercer-Erwin broke the trust the government placed in her.

Mercer-Erwin had told WFAA in 2019 that “we know who our clients are -- we collect all their information.”

So, was her claim accurate?

“We found that not to be truthful,” prosecutor Ernest Gonzalez told WFAA in a 2021 interview.

In court records, federal investigators cited four drug planes – registered through Mercer-Erwin's trust company – just from 2020. Two were seized loaded with drugs. A third one burned on a clandestine airstrip in Venezuela. The fourth was shot down by the Venezuelan military.

After authorities determined a fifth plane had been bought with drug money, the real owners let the U.S. government keep it.

“They weren't doing any vetting at all,” Gonzalez said of Aircraft Guaranty. “Some of these planes were being placed in the hands of drug traffickers, and she knew that.”

And that’s not all.

When law enforcement seized some of the company’s aircraft loaded with drugs, investigators say Mercer-Erwin and her daughter Kayleigh Moffett sought to distance themselves by either deregistering the planes or transferring ownership elsewhere.

One Gulfstream jet they were linked to changed ownership three times in one day in December 2019. On that day, prosecutors say an aircraft museum sold the plane to a company linked to the Mexican Sinaloa Cartel. That company then sold it to Heriberto Calderon Gastelum, a convicted drug smuggler, who then turned over ownership to Aircraft Guaranty Corp. to register in trust.

Prosecutors say it’s an example of the shell game the company played with drug dealers.

“A simple Google search would have shown that that individual had been prosecuted in the United States,” Gonzalez said in our 2021 interview.

Six days after that plane changed hands three times, it flew to Mexico. Then, 67 seven days after that, authorities in Belize seized the plane, which was loaded with 2,310 kilograms of cocaine.

In 2019, Massachusetts Congressman Stephen Lynch proposed legislation that would require the identity of planes' real owners to be on file with the FAA -- an attempt on his part to close the trust loophole.

“We want someone to be held accountable,” Lynch told WFAA in 2019. “We want to be able to put a face of a person with that aircraft.”

Lynch’s legislation stalled in Congress, but prosecutors moved forward just the same.

Chapter 3 Federal criminal indictment

In 2020, a grand jury indicted Mercer-Erwin, her daughter and six others.

The indictment said after Mercer-Erwin and her daughter concealed the “true ownership” of aircraft.

“There were occasions where the plane was put in trust, then that plane was repeatedly sold to other individuals and they have no idea who the truthful owner of that plane was,” Gonzalez said.

After WFAA’s investigation spurred a federal criminal probe into Aircraft Guaranty, the government decided to expand its review to include dozens of other trust companies.

When investigators began digging into Aircraft Guaranty’s records, they found something else that shocked them -- a Ponzi scheme.

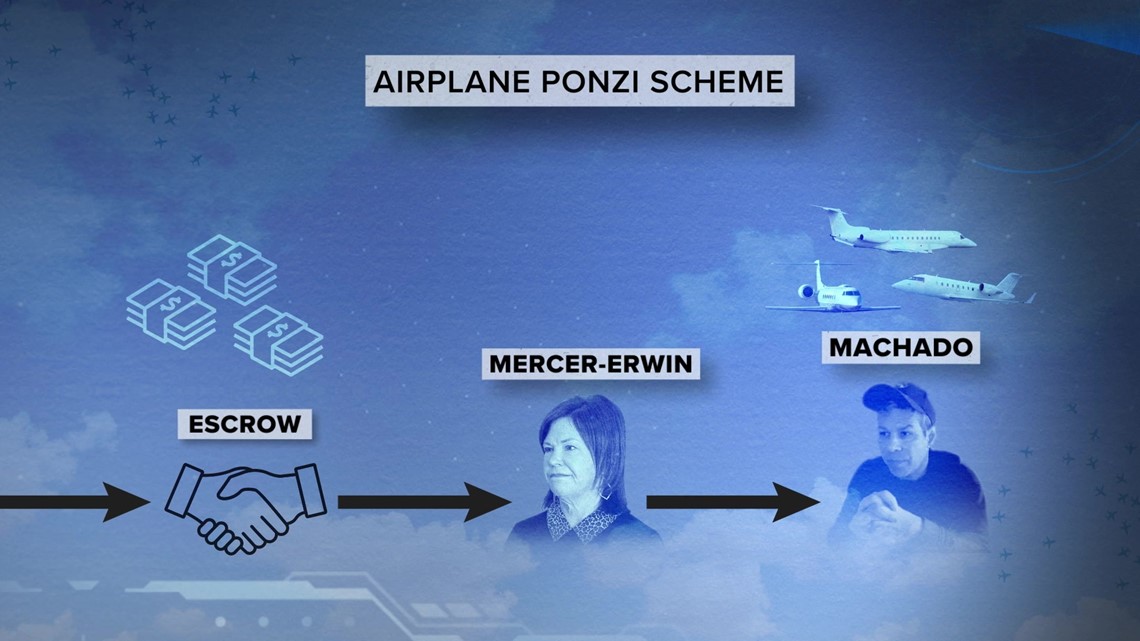

Investigators discovered that Mercer-Erwin and an alleged accomplice named Federico Machado, a Florida-based aircraft broker, engaged in a scheme to bilk investors through fake plane deals.

Machado had put planes in trust with Aircraft Guaranty, and is also accused in the indictment in connection with the narcotics trafficking allegations.

How’d the Ponzi scheme work?

Investigators say investors wired deposits to escrow accounts at Oklahoma City-based Wright Brothers Aircraft Title, owned by Mercer-Erwin.

The escrow money was to be used as a fully refundable deposit so Machado could buy planes, according to signed agreements. In return, the investors were supposed to receive large fees. The money deposited into the title company was to be held in an escrow account, only to be returned to the investors.

But prosecutors say the money didn't remain in escrow, and the planes either didn’t exist or weren’t for sale.

“The planes they were asking investors to put deposits on were ghost planes,” Gonzalez said. “He even got individuals to pose as sellers of these planes. They continued to do more plane deals to cover up the previous plane deals, which is your typical Ponzi scheme.”

We wanted to ask Machado about all this ourselves, so we dug into records, tracked down people who knew him and we found him thousands of miles away from Onalaska -- under house arrest in his native Argentina.

“I have a story to tell,” Machado said during a Zoom interview with WFAA.

Machado is fighting extradition to the United States on the drug smuggling and fraud charges filed in the Mercer-Erwin indictment.

“The way they portray me in the indictment is like you're talking to El Chapo,” Machado said. “I'm not a saint, right? I made mistakes, but I'm not a narcotrafficker.”

We asked him about the Ponzi allegations.

“It's a group of a few people,” he said. “They thought they were investing in something. They invest in something else.”

We wanted to know where the investor money had gone. His answer? Not into buying planes, but rather his Guatemalan mining operation.

“There's not [a] line of old ladies that got cheated,” Machado told WFAA. “It can get fixed. If God gave me freedom, I will fix it, I will pay them back. It has nothing to do with drugs.”

Machado says he’s far from a criminal. Instead, he claims that he’s a humanitarian who gave the local indigenous people a better life through his financial deals and mining operation.

“We were giving jobs to the people,” he said. “They were quite happy.”

We asked Machado about the allegations that Mercer-Erwin – and her trust company – registered planes for drug dealers.

“[It] doesn’t strike me that an old lady from Oklahoma is going to go and put her planes under their name and carry drugs; it's just stupid,” he said. “It made no sense to me.”

But would it make sense to a jury?

Chapter 4 The trial

In April, the story that began in Onalaska with WFAA’s investigation moved to federal court in Sherman. That’s where Mercer-Ewin went on trial.

Never before had an aircraft trust company owner faced trial accusations of putting planes into the hands of drug traffickers.

“She certainly didn't fit the profile from a TV show like Netflix, or a movie depicting Colombian narcotraffickers,” said Jesus Daniel Romero, a retired naval intelligence officer. “But in today's world, narcotraffickers and transnational criminal organizations are made up of people like Mercer.”

At the start of the trial, it was the Ponzi scheme involving as many as 100 fake plane deals that took center stage.

WFAA confirmed that investors lost at least $240 million. Prosecutors showed jurors a secret ledger kept by Machado and Mercer-Erwin detailing each of the plane deals, and what happened to the money. The ledger and bank records revealed that Mercer-Erwin made $4.9 million. Machado pocketed $75 million.

When Mercer-Erwin took the stand, she denied to jurors that she was involved in the Ponzi scheme. Rather, she claimed Machado had scammed her and denied having pocketed any money from the Ponzi.

She also denied having been involved in drug smuggling and claimed to have thoroughly vetted owners of planes she placed in trusts.

Prosecutors, however, argued Mercer-Erwin turned a “blind eye” to possible drug connections by plane owners. They said she ignored warnings that the planes she put in her trust were being used by drug traffickers.

In 2020, about a month before the Belize plane became the biggest seizure in that nation’s history, another Aircraft Guaranty jet loaded with nearly two tons of cocaine landed in a Guatemalan jungle.

Video of that plane went viral within days.

Machado sent Mercer-Erwin a message, telling her that her plane had been “rescued from the landing strip in Guatemala.”

“It’s no longer registered,” she responded.

She failed to tell the U.S. government that the plane had been seized, which prosecutors and investigators told jurors was evidence of her complicity in drug smuggling.

“That plane just simply showed up into Guatemala in the middle of the jungle, but yet the owners of the plane never asked for their plane to be returned,” Romero said.

Romero arrived in Guatemala in 2017. He served as chief of the Joint Interagency Task Force South in Guatemala, a multi-U.S. agency set up to detect and monitor drug trafficking.

He testified at Mercer-Erwin’s trial.

“We were not prepared for the amount of aircraft that came in through Guatemala, and Belize, and Honduras,” he said in an interview with WFAA.

Romero said drug traffickers graduated from slower single- and double-prop planes to speedy jets that could carry several tons of cocaine worth $200 million or more. The planes of choice were Hawker and Gulfstream jets.

Trial testimony showed cartels flew U.S.-registered aircraft from Mexico to cocaine-producing countries in South America to be loaded. The planes flew to clandestine airstrips in Central America, and the drugs were then smuggled north into the United States.

If the jets crashed, it was the cost of doing business. Often, the jets were intentionally destroyed -- either burned or buried -- making it even more difficult to trace their ownership.

Romero told WFAA that pilots flying the U.S.-registered aircraft in Mexico would turn off their planes’ transponders to avoid detection as they often flew to Colombia and Venezuela to pick up drugs. Within hours, the planes were loaded with cocaine, and then flown to Central America to be offloaded by awaiting crews.

“The amount of planes that were coming into the region were creating lots of violence,” Romero said. “They were creating mass chaos.”

Chapter 5 Reduction in drug flights

What happened after Mercer-Erwin’s indictment may be the most damning piece of evidence against her.

“We saw direct disruptions to cocaine air trafficking -- periods of 30 to 90 days where we didn't see a single aircraft,” Romero said. “We attribute that as a result of Aircraft Guaranty’s indictment. That caused the biggest disruption to the cocaine flow.”

Over two days, high-ranking Latin American officials testified that they also saw drug flights fall from hundreds annually down to just a few.

Dressed in full military uniform, Colombian Air Force Lt. Col. Alex Humberto Landino told jurors that the number of jets carrying drugs in the Caribbean dropped 59 percent from 2020 to 2022. He testified that he believed the indictment played a big role in the disruption.

Landino, director of his country’s air and missile defense, also told jurors that there had been a 29 percent drop during that period in cocaine seizures in Central America. He estimated that the disruption in flights represented a $1 billion loss to narcotraffickers.

“As soon as this case was indicted, the effect was immediate [and] the number of planes with drugs diminished considerably,” Gonzalez said.

After a day and a half of deliberations, the 12-member jury convicted Mercer-Erwin of being a drug trafficker. They also convicted her in connection with the Ponzi scheme.

“The jury got to see how drug trafficking works, how everybody plays a part,” Gonzalez said.

After the jury delivered its verdict, Mercer-Erwin left the courthouse in handcuffs and shackles, escorted by U.S. Marshals.

Chapter 6 'A landmark case'

“It is a landmark case,” Gonzalez said. “This is a unique case in the United States, one involving airplane trusts that no one had been paying any attention to. Obviously, your piece, WFAA’s piece, was instrumental in giving us the focus to see what exactly was going on.”

The same week that Mercer-Erwin’s trial began, Congressman Lynch reintroduced the Aircraft Ownership Transparency Act, which would require that the identity of foreign owners of planes held in trust be on file with the FAA.

Under the proposed bill, specific identifying information would need to be on file, including a nonexpired driver’s license or a passport with a photograph and date of birth.

Mercer-Erwin now awaits sentencing. She faces up to life in prison. Her daughter had taken a plea deal for five years of probation before the start of her mother's trial.

“It would be foolhardy to think that this doesn't change things,” said David Hernandez, an aviation finance attorney based in Washington, D.C. “I think this is a game changer for people for trust companies... to ensure that that they are fully aware of who's operating their aircraft and do very comprehensive due diligence.”

He continued: “They're terrified to think that they're going to be held accountable for what happens to a particular aircraft owned by one of their beneficial owners.”

A federal judge also signed an order authorizing the government to seize as much as $50 million from Mercer-Erwin.

After the trial ended, we returned to Onalaska to talk to lifelong resident Zachary Davies, who now serves on the town’s city council.

“I thought you drove four hours on a story that I really just couldn't wrap my mind around because it didn't make any sense,” he said of WFAA's initial investigation. “Onalaska, Texas: We got 3,000 people [and] no airport. I'm thinking, what's really going on?”

Over the years, though, Davies kept up with WFAA's news coverage of the case.

“One of the biggest just shockers for me is we had this under our nose the entire time,” he said. “Y'know everything was real quiet -- until it wasn't. All hell broke loose.”

Got a tip? Email investigates@wfaa.com.