MONROE, Louisiana — Erie Moore Sr. loved to sing.

He’d regale passersby with his deep baritone voice.

It’s how his adult children want to remember him.

But they cannot get the images of how he was treated inside a jail run by LaSalle Corrections out of their minds.

Five years ago, Moore was arrested for a misdemeanor disturbance charge. Jail surveillance videos showed guards repeatedly pepper sprayed him, hit him in the head, knocked him to the ground and dropped him to the floor.

Moore died of brain injuries.

“The hardest part is not knowing what happened, why it happened,” said his daughter, Tamara Green, who along with her two adult siblings are suing LaSalle Corrections over their father’s death.

LaSalle declined to talk to WFAA for this story. In response to the Moore family lawsuit, the company said it did nothing wrong.

For more than a year, WFAA's "Jailed To Death" investigation has been showing you videos of prisoners screaming for help and gasping for breath inside Texas jails run by LaSalle, a private, for-profit company.

Over and over, a WFAA investigation found inexperienced and undertrained guards using too much force and not asking for medical care in time.

But what happened to Erie Moore did not occur in a Texas jail.

He was in jail in Louisiana, the state where LaSalle was founded.

“Historically, that’s the way they operate,” said Steven Hansen, an attorney in Monroe, Louisiana.

Hansen represents five prisoners who in 2016 were booked into the Richwood Correctional Center near Monroe. It’s run by LaSalle.

According to a federal court records, five guards questioned the prisoners about gang activity and threatened them with pepper spray. When the prisoners refused to answer questions, the records say the guards took them into a room without security cameras.

While the inmates were “handcuffed, compliant, kneeling on the floor, not posing a physical threat to anyone,” the records say a jail captain sprayed one inmate in the eyes and then passed the can to the other officers. A lieutenant, a sergeant and two officers then sprayed the other inmates, records show.

“In order to cover up the officer’s actions and to conceal the fact that they had unlawfully sprayed” the inmates, the guards falsified reports and turned in a “false cover story about the incident,” according to federal court records.

Hansen said his clients were also pepper sprayed in the anus in addition to the eyes. He said one of his clients lost some of his vision as a result of the attack.

He said the guards, who are black, accused his clients, who are white, of being white supremacists.

According to Hansen, there is jail surveillance video showing what the prisoners looked like before being taken into the room without cameras, and what the men looked like afterwards. The video has never been released publicly.

“These people treated the inmates as if they were some terrible animal, and you felt sorry for them,” Hansen said. “This was such reprehensible conduct that I couldn’t live without taking the case.”

Four former guards are now in federal prison over what happened to Hansen’s clients. A fifth former guard died before being sentenced. A federal civil rights lawsuit against LaSalle is ongoing.

LaSalle has denied any wrongdoing in the case.

Mental breakdown

A year earlier, in October 2015, Erie Moore Sr. was having a mental breakdown.

He began following a Louisiana state trooper, who eventually pulled him over. Moore was “extremely irate” and “cursing and shouting threats,” according to police documents. Moore threatened multiple times that he was “going to force a police officer to shoot him,” records show.

The trooper’s dash cam video shows that he asked Moore if he was off any medications. Moore denied being on medications. “I want to know what I can do to help you because something ain’t right with you,” the trooper told Moore.

Ultimately, the trooper wrote him a ticket and let him go.

The next day, on the morning of Oct. 12, 2015, a Monroe police officer encountered Moore in a donut shop, where according to police records, Moore was shouting and cursing at an employee. Moore told the officer that he believed the officer was going to “kill him.” The officer took Moore into custody on a misdemeanor disturbing the peace charge.

Monroe had a contract with LaSalle to house their prisoners, so the officer took Moore to the company’s Richwood Correctional Center, according to court records.

Moore had no criminal history, and had not been in jail before, his family said.

Jail policy said all offenders will undergo an intake medical screening upon arrival. That never happened in Moore’s case, according to his family’s lawsuit.

Guards placed Moore in an isolation cell that was monitored by video cameras in the central control room, according to the family’s lawsuit. Initially, he was in there by himself. Depositions taken in the lawsuit and interviews with investigators show that guards were aware that Moore was having psychiatric problems.

“He was standing there talking up the camera saying he was God,” a LaSalle jailer told investigators from the sheriff’s department.

But instead of following procedure and isolating Moore and getting him a mental evaluation, investigative records show a lieutenant on duty ordered guards put a prisoner named Vernon White in the cell with Moore.

Jail records show White, who was in jail on misdemeanor warrants, had just gotten into a fight with another inmate.

Moore and White spend nearly 20 hours together in a cell.

“Why would you put a hostile inmate that was fighting in another cell with a man – clearly, he wasn’t OK?” said Tamara Green, Moore’s daughter.

In a deposition, the jail lieutenant -- who later was promoted to captain -- testified that he was aware that other cells were available when he placed White in that cell with Moore.

The lieutenant acknowledged that the normal protocol would be to keep prisoners who had exhibited violent behavior separate.

Not long after putting White in the cell, jail records said the lieutenant heard Moore kicking on the cell door. He commanded Moore to stop. When Moore did not comply, he used pepper spray on him.

The next morning, on Oct. 13, 2015, White and Moore got in a physical confrontation in the cell, jail records show. When guards went in to pull them out, a guard again used pepper spray on Moore.

Still the inmates were not separated. The situation became deadly around 5 p.m. that day.

On a jail surveillance video, Moore paced around the cell and yelled and talked to White. He got in a fighting stance and put his hands around White’s throat. Moore pulled back his fist as if to hit him. He attacked White and pushed him into a corner of the cell not visible on camera.

Moore approached White and appeared to be stomping, but it’s not visible on camera. Moore then disappeared from camera view and into that corner with White for about six minutes before he reappeared.

Nobody intervened.

About 17 minutes after White disappeared from camera view, a guard brought two food trays. According to deposition testimony, the jailer was supposed to make sure each inmate takes their own tray. The jail video shows Moore took both trays.

Another 25 minutes elapsed before a jailer looked through the window and saw White on the floor, critically injured.

“He was shaking, and blood was coming out of his mouth,” the jailer later said of White, according to an audio recording of an interview he gave investigators. “(His teeth) looked like it was gone.”

Surveillance cameras showed guards opened the door and rushed in. They removed White, who later died from head and neck injuries, his autopsy shows.

Moore had taken off his pants and was defecating on the floor of his cell. One guard pepper sprayed Moore, who was still squatting. A jailer then hit Moore in the head, knocking him to the floor.

Later in a deposition, the jailer testified he “passively push[ed] Mr. Moore.” He denied punching him. He also testified Moore “was about to charge me,” but the video shows Moore continued to squat and made no effort to get up and come toward officers when they entered the cell.

After removing White from the cell, guards left Moore alone in there for about 40 minutes, surveillance video showed. When guards came back in, Moore was sitting on the bed. He covered his face with his shirt. The lieutenant sprayed him. The guards left and came back wearing gas masks. Moore stood and faced the bunk. The lieutenant lifted him off his feet, carried him out of the cell and threw him to the ground.

The lieutenant later testified that that he “placed” Moore “on the ground firmly.”

Guards then handcuffed Moore and grabbed his feet. Two guards picked him up by the restraints and carried him a few feet when one of them slipped and dropped Moore on his head.

Jailers picked Moore up and carried him to the same room without video cameras. He was in that room for an hour and a half, investigative records show.

“I believe Mr. Moore was taken into that room to teach him a lesson,” said Nelson Cameron, a Shreveport attorney representing the Moore family.

LaSalle’s response

LaSalle officials did not respond to WFAA’s request for comment.

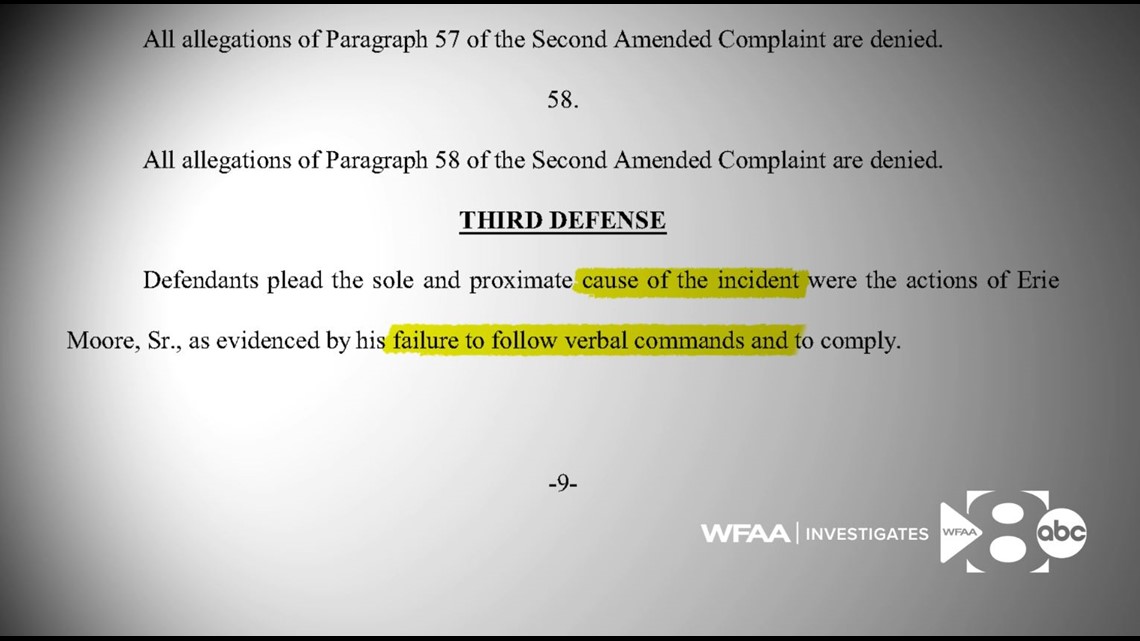

But in response to the Moore family’s lawsuit, the company wrote “any force used upon Erie Moore Sr. was reasonable and necessary under the circumstances.”

The company blamed Moore for his own injuries and said the “cause of the incident” was Moore’s "failure to follow verbal commands and to comply.”

Later that night, sheriff’s deputies from the Ouachita Correctional Center arrived at the jail to transport Moore to their facility so he could be questioned in White’s death.

Sheriff’s officials wrote in statements that Moore was “unconscious” and “unresponsive” in that room without cameras when deputies arrived.

One of the deputies told investigators that Richwood jailers said “that he was faking sleep and had peed on himself on purpose.” His body was “completely limp” when authorities moved him to a vehicle.

When he arrived at their facility, records show that medical staff examined him and found “multiple red marks on the subject’s face and head,” “a cut above his right eye” and a “large bump on his head.” Sheriff’s officials took several pictures to document his injuries and sent him to the hospital. Medical staff also found that his pants were “wet from pepper spray.”

When he arrived at a Monroe hospital, a CT scan showed he had “a bleed on his brain … and a fracture to his skull,” records show.

He was in such critical condition that he was airlifted to a Shreveport hospital.

Meanwhile, Moore’s children had been trying to find him for days. By the time they located him, he was already on life support.

“It just wasn’t him,” said his daughter, Tiffany Robinson. “He’s not breathing on his own. It’s just not him.”

Moore never regained consciousness. His children said they sang songs to him as he slipped away a month later.

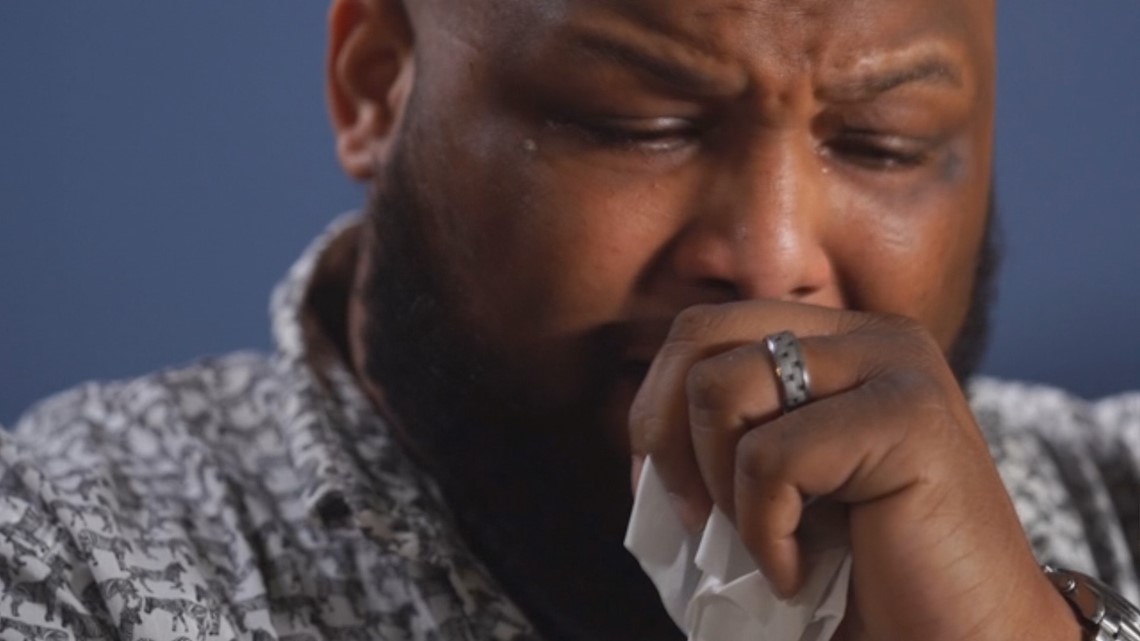

Five years later, they are still trying to understand how their father could end up with such massive head trauma.

“How does he suffer these blows?” Erie Moore Jr. said. “How does it get to a point where we’re having to make a decision on having to pull the plug for a disturbing the peace?”

“He didn’t deserve this,” he said, through tears. “He had a good heart.

The coroner found Moore Sr. died of “blunt force head injuries.” His death was classified as a homicide.

White’s death was also ruled a homicide. It was never determined exactly who gave White his injuries.

No one was ever charged in either death.

Kenny Sanders, a former training academy commander and expert in jail procedures, was hired by the by the Moore family to review what happened.

In a 23-page report, he said Richwood jailers should have realized that after repeatedly pepper spraying Moore that there was some other “underlying problem” that could not be resolved by “using force,” and that they should have gotten Moore assessed.

He also criticized the decision to put White and Moore together. “Good correctional practice is to keep violent inmates segregated from each other,” he wrote.

Overall, Sanders said, training at LaSalle’s jail was “grossly insufficient.”

“The proper training may have been able to save more than just my father’s life,” Erie Moore Jr. said.

Email: investigates@wfaa.com