Learning to walk again for Don Sherman has meant learning to laugh through the pain.

A stroke in 2012 almost killed him and forced his retirement from the FBI. Now, in front of his apartment, he steps across a “Come Back with a Warrant” doormat, a not-so-subtle reminder of his former life. He jokes that he tells his neighbors that visitors are his parole officers.

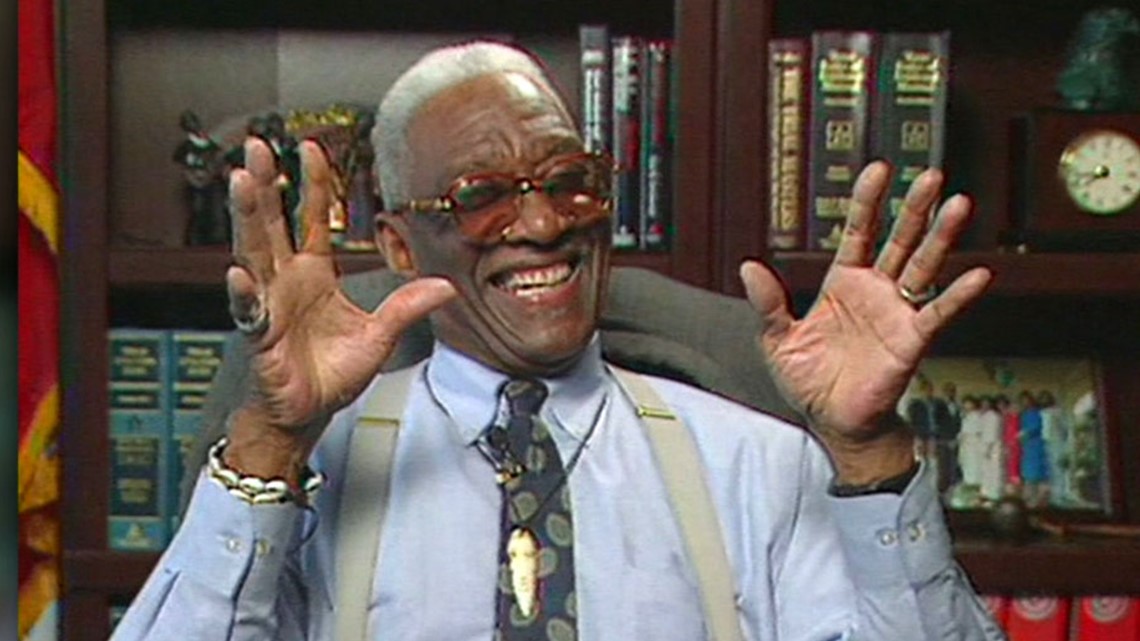

For 20 years, Don Sherman was Public Enemy No. 1 for some of Dallas' most corrupt politicians.

Investigations he led put sitting council members in prison: Paul Fielding in the 1990s and Don Hill in the 2000s.

He also led the investigations that led to the prosecutions of the now-deceased Dallas city council member Al Lipscomb and against former state Rep. Terri Hodge. He oversaw the raid of Dallas County Commissioner John Wiley Price’s home and office.

A jury later found Price not guilty of bribery and fraud and deadlocked on charges of tax evasion.

“Dallas was a target-rich environment for sure,” Sherman said.

Sherman’s finishing up a book called He Changed My Life detailing his stroke recovery and how his Christian faith is seeing him through.

“By the grace of God, I made it,” he said. “That’s the story I want to tell people. My Savior lives.”

But it was in his darkest days after he got sick that Sherman would find out who his real friends were. The taciturn, just-the-facts G-man who rarely showed emotion found himself dependent on others. Some friends disappeared, he said.

But one friend remained steadfast and never wavered.

His name is Roger Hoffman, a friend he met in the unlikeliest of circumstances. It was not a pleasant acquaintance for Hoffman in the beginning.

Hoffman was a target in one of Sherman’s investigations.

So how did the G-man and the felon become the best of friends?

Let’s rewind to the mid-1990s.

Back then, Sherman was a young FBI special agent in Dallas investigating allegations that defense contractors were paying kickbacks in an operation called Operation Cobra Nest. Sherman’s undercover name was “Don Shuman” – close enough to his real name that if someone recognized him he could explain it away. He became the “bagman” delivering the “bribes.”

Along the way, he met Hoffman, a business partner and friend of then-council members Fielding and Lipscomb.

Fielding and Lipscomb had been shaking down businesses, prosecutors later said. Hoffman knew of their illegal activities but hadn’t reported it.

One day, Sherman showed up at Hoffman’s Plano home and told him his real name and showed his badge.

“May I come in and talk to you?” he asked Hoffman.

Sherman explained to Hoffman that he was in real legal trouble. There was a way to mitigate it. He could be an informant and help Sherman nab Fielding and Lipscomb.

Hoffman was afraid. He feared for his safety and his family if he helped the FBI. Sherman assured him he would protect him, and Hoffman agreed to cooperate.

“I told him, ‘If you cooperate with me, I’ll do everything I can to help you,’” Sherman said.

Sherman put in a good word with prosecutors. Hoffman pleaded guilty to failure to report a crime. He received three years of probation.

After his conviction, Hoffman’s life spiraled out of control. His marriage, his finances, everything was in a shambles. Desperate, Hoffman reached out to the one person who could possibly understand his plight. He called Don Sherman.

“I said, ‘I’m desperate. I’m in a bad situation,’” Hoffman recalled. “’Is there anything you can do to help me?’”

Sherman’s response was hardly what Hoffman expected.

“I told him, ‘Roger, I don’t have the answers for you, but I know who does. If you want, I’ll take you to meet Him,’” Sherman said, explaining that he’d pick him up and take him to church the following Sunday.

Hoffman, raised in the Jewish faith on Long Island, New York, began attending Prestonwood Baptist with Sherman. Hoffman converted to Christianity in 1996.

“From that point on, he became my brother in Christ,” Sherman said. “It’s the first time I struck up a good friendship with somebody I arrested for sure.”

Sherman had no idea back then how fortuitous that friendship would be for him.

In 2012, he went in for a biopsy so doctors could check out a walnut-sized mass near his heart. After the biopsy, he was in his hospital room and began having difficulty breathing. He was having a stroke.

The neurosurgeon told his family he had 98 percent of chance of dying in surgery and said if he did make it, he would probably be bedridden. The surgeon removed a piece of skull from his brain to relieve the pressure.

“That it was not my day to die,” he said.

He woke up unable to move his left side. He could not talk. He could not sit up in bed. He was on a feeding tube. He began to pray and try to negotiate with God. “‘They’re saying I’m not going to get out of bed. That can’t be right,’ I said. ‘Lord, if you just get me back on my feet, I’ll tell the whole world what you’ve done.’”

Sherman has faith that he will one day walk again without a cane.

With the help of a grueling physical therapy regimen, he’s learned how to walk again and regained partial use of his left hand.

Hoffman, he said, is a big reason why.

“He has really encouraged me and kept me going when there were tough days and there was no one else there,” Sherman said.

On the day we met Hoffman, he was taking Sherman to the gym for physical therapy. They both laughed as they noticed the camera we’d put in the car.

“At least I’m disclosing this time that I’m taping you,” Sherman chuckled.

“That’s true. That’s a one up,” Hoffman replied.

Last year, Sherman served as the best man in Hoffman’s wedding. “It’s my single greatest accomplishment as an agent that I was able to do that for him,” he said, tears in his eyes. “I’m proud of him, of what he’s done.”

“He certainly didn’t deserve what this horror has been and I wasn’t going to leave his side,” Hoffman said. “He’s more of a family member than a friend.”

Email teiserer@wfaa.com