ARLINGTON, Texas — Angelique Estes lived a nightmare inside an unlicensed Arlington boarding home.

She says she was kicked, hit and left lying in her own waste for days before police rescued her this past December.

“I was held against my will,” says Estes, who can’t walk and has cerebral palsy.

She says she attempted suicide to try to get her caregiver to call for an ambulance. Still, they would not let her leave, Estes said.

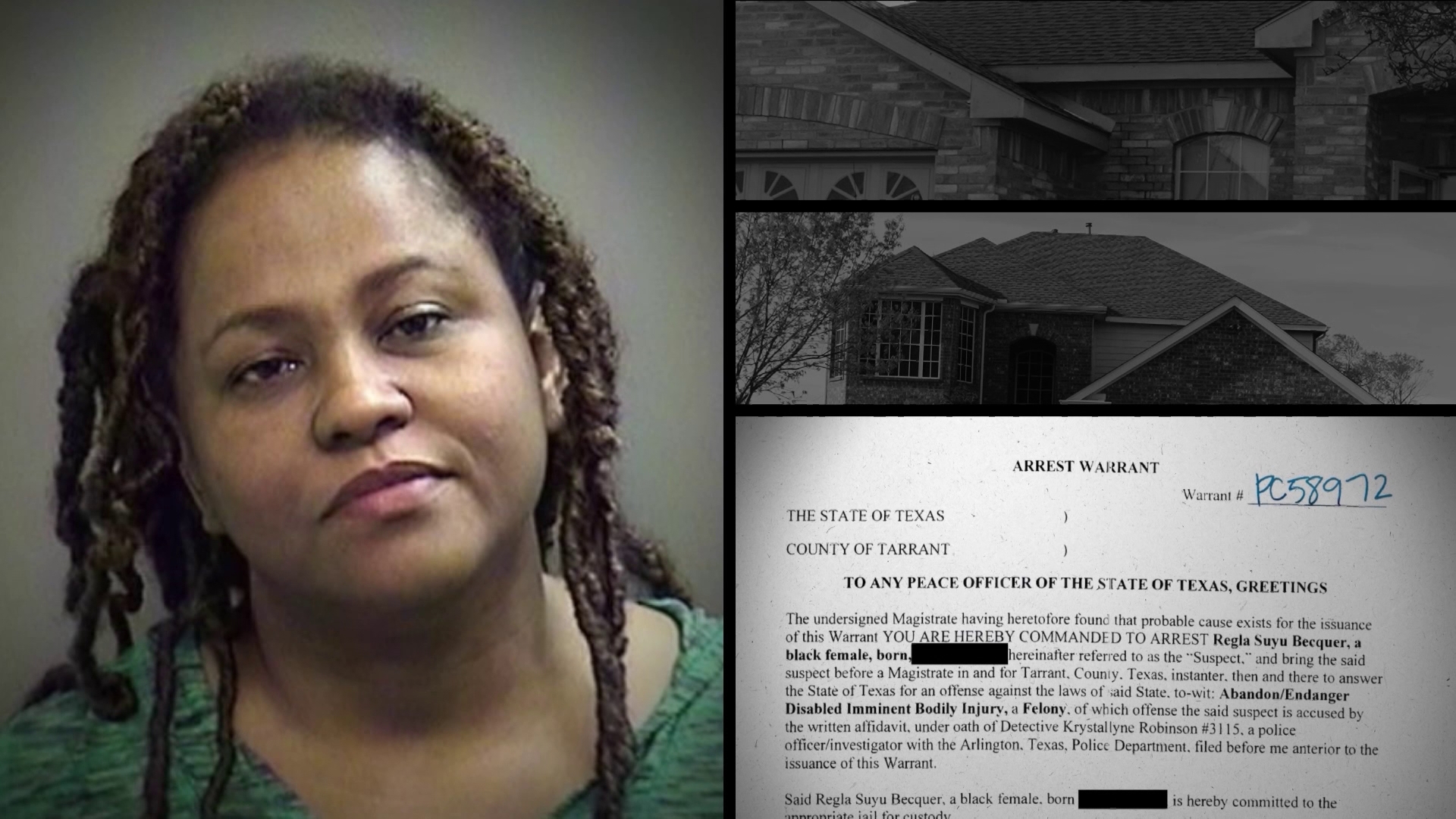

That caregiver, Regla “Su” Becquer, now sits in the Tarrant County Jail accused of abusing Estes. Her bail is set at $750,000.

“I can’t believe how bad things were,” Estes said.

Becquer ran a string of unlicensed boarding homes in Mansfield, Arlington and Grand Prairie that are now at the center of a police investigation into as many as 20 deaths. Two of the deaths involved wills that resulted in Becquer or her family inheriting the person’s estate, according to court records.

In one case, the person’s estate was valued in excess of $300,000, court records show.

Becquer declined repeated interview requests.

She is not charged in connection with any of the deaths, but police say they anticipate seeking more charges against Becquer and possibly others.

“These are the perfect victims,” Arlington Police Lt. Kimberly Harris said in early March during a press conference. “Some of them were being physically assaulted. Some of them were being neglected.”

Since police announced their investigation in March, WFAA has uncovered a largely unregulated business model that can allow unscrupulous operators to abuse vulnerable people.

“This is one step above being unhoused. One step above being under the highway bridge,” said Dennis Borel, who recently retired as executive director of the Coalition of Texans with Disabilities.

State law allows boarding homes to operate without oversight in many cases.

Cities and counties can license and inspect boarding homes with at least three residents.

Fort Worth and Dallas have ordinances regulating boarding homes. But most cities lack ordinances, and that includes Arlington, Grand Prairie and Mansfield – the cities where Becquer operated her homes.

“Su was about the money,” said Victor Lister, a former employee of Becquer’s.

According to Lister and police records, he and Becquer parted ways after he and a client accused her of stealing the client’s food stamp card.

“Anybody that she could gain some from, she would do everything in her power to disconnect them, ...so they couldn't have no contact with anyone in their family, any friends,” he said.

Lister says whenever Becquer’s clients died, she would keep their medications and give them to other clients – an account backed up by police statements and records.

He says she kept the medications in the trunk of her car.

“A dead man’s pharmacy is what I called it,” he said.

Family members told police and WFAA that Becquer isolated their loved ones from them. Estes told police and WFAA she was forced to take a minty-tasting liquid that made her feel disoriented and out of it.

Court documents say Estes smelled of “urine and feces” when police found her Dec. 13 living inside one of Becquer’s boarding homes.

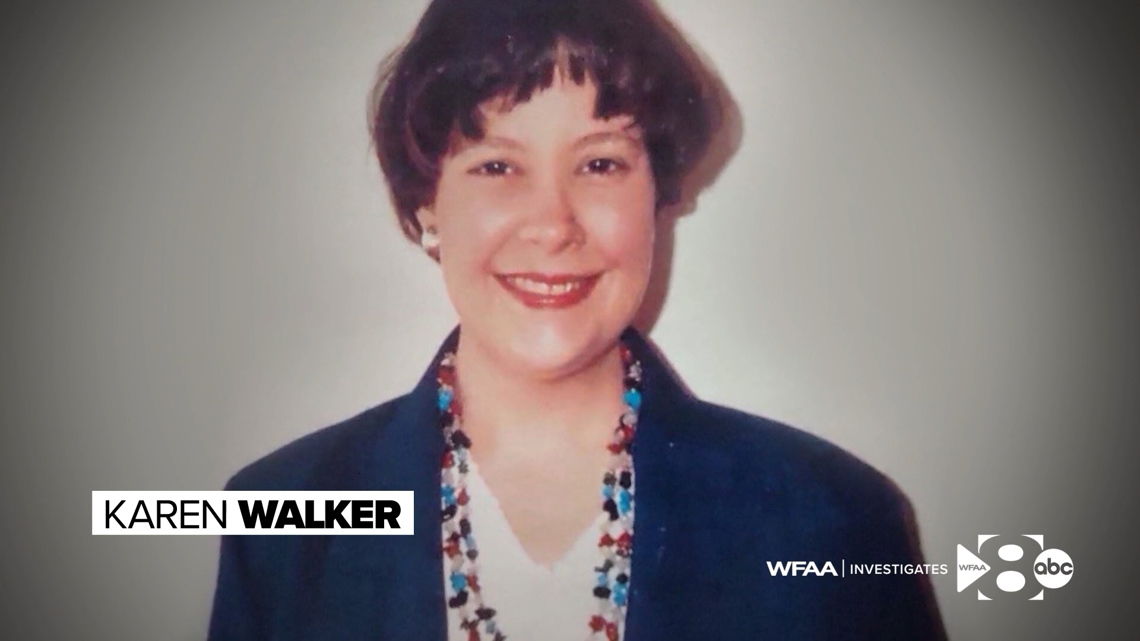

Records show the boarding home used to belong to Karen Walker, another of Becquer’s clients.

Walker had diabetes and kept falling and ending up in the hospital, which is how she ended up under Becquer’s care.

Roger Simon, Walker’s cousin, says Becquer moved Walker out of her home and into one of her other boarding homes.

“When Karen was at this home, she didn't have a private phone,” said Simon, who lives in Illinois. “In order to communicate I had to call, Regla's phone.”

He told WFAA his cousin often sounded disoriented. In one call, he says, she told him, “I gotta get out of here. They’re trying to kill me.”

She died in late October 2022. An autopsy found she died of cardiovascular disease.

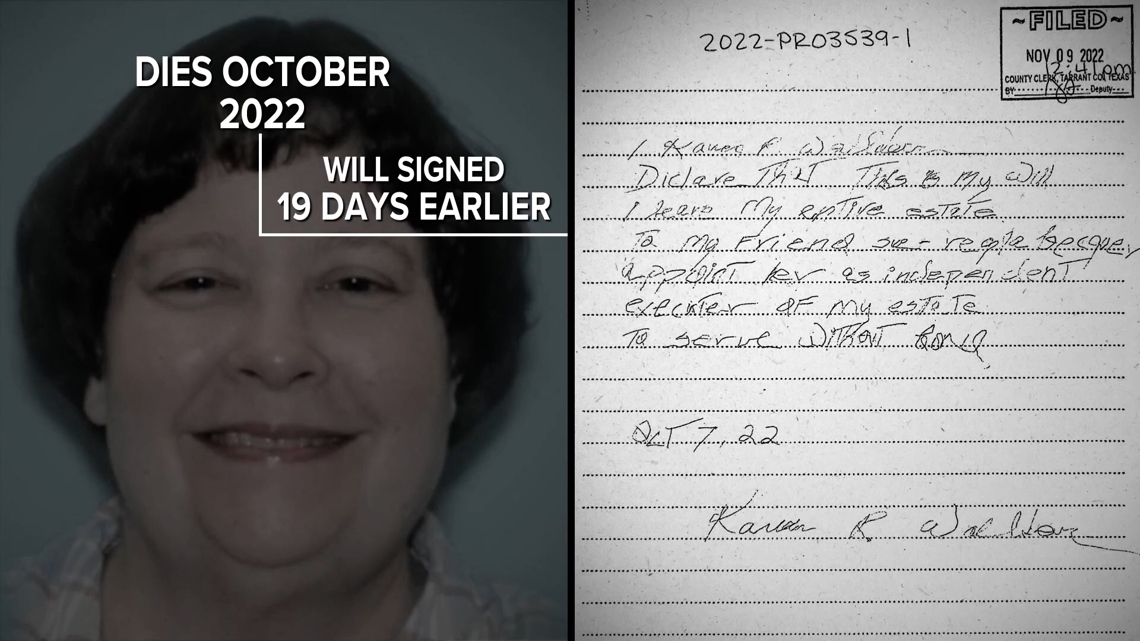

A one-paragraph handwritten will dated 19 days before her death says, “This is my will. I leave my entire estate to my friend, Regla Su Becquer.”

“I thought it was fake from the beginning,” Simon said.

He said Walker’s financial advisor told him the signature on the will was not his cousin’s signature.

Simon told WFAA that he received a call from Becquer’s attorney, Samuel Bonney, warning him that it would be costly to fight it. Citing client confidentiality, Bonney declined comment to WFAA.

“It was going to cost an astronomical amount of money to contest it and I'm a senior citizen surviving on Social Security,” he said.

Simon, in ill health himself and partially blind, says he opted not to fight it in the end.

Records show Becquer inherited an estate valued at $331,000. That included Walker’s house valued at $223,000, and more than $75,000 in two bank accounts.

“I felt that she was just a money grabber,” Simon said. “That's all she cares about is getting money any which way she can.”

Police have opened a forgery investigation into Walker’s will.

Because the will wasn’t witnessed, two people had to swear it was it was Karen Walker’s handwriting.

Becquer was one of the two people who swore it was, in fact, Walker’s handwriting.

This is where Grand Prairie resident Tiffany Brown comes into the story.

According to court records, Brown swore that she was “well-acquainted” with Walker’s handwriting and signature. She swore that it was written by Walker.

A WFAA investigation found that Brown also runs boarding homes.

The state’s health and human services agency previously sued Brown for running an unlicensed assisted living facility in Grand Prairie.

In March, Grand Prairie police responded to a home where a 76-year-old woman had been found “covered in feces” and “it appeared like she had not been tended to in multiple days,” according to police records. Medics told police that the victim had “sores on her buttocks that had come from not moving” and it was so bad that the woman “could not lay on her back.” She was taken to a local hospital.

That same month, police were called to the hospital to speak with a 56-year-old woman in a wheelchair. She had “developed bed sores to the point where a bone in her back is exposed and needed surgery,” records state. The woman told police she paid Brown $2,000 to a month to care for her.

Until recently, Brown lived in a home on Lorenzo Drive in Grand Prairie. Her former landlord said she evicted Brown from the home after finding out from police that she was operating an unlicensed boarding home in the house in violation of her lease.

Brown was arrested on two criminal negligence charges. She was released on bail totaling $35,000. Her bonds have since been held insufficient and an arrest warrant has been issued for her arrest.

Brown declined to comment through her attorney.

“Well, it truly shows what she is,” Simon said of the abuse allegations outlined in police records. “And if she can do that, she can lie.”

WFAA also discovered a second will by another of Becquer’s clients.

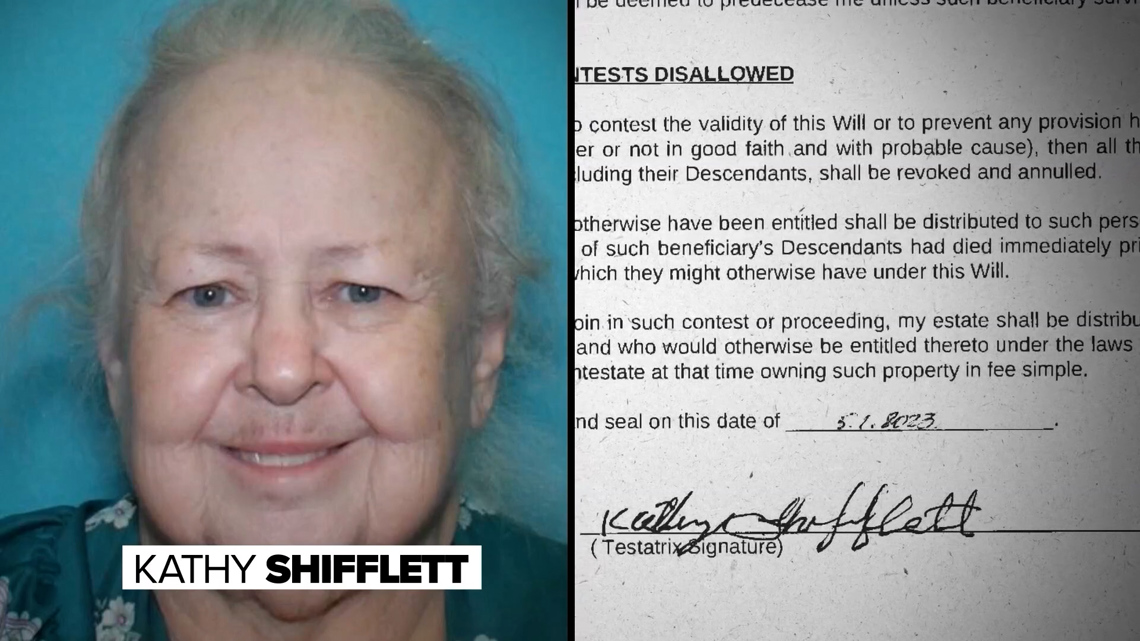

Kathy Levell Shifflett’s will was dated May 2023. She died three-and-a-half months later.

That will awarded Shifflett’s Irving home to Becquer’s mother, along with any money in Shifflett’s bank accounts.

Police confirmed to WFAA that Shifflett’s death is among those under investigation.

WFAA found Becquer’s mother, Mariana de la Caridad Garcia, living in one of the former boarding homes in Grand Prairie.

Garcia indicated in an initial interview that she did not know Shifflett. She denied knowing anything about the will or about owning a house in Irving.

“I don’t want to make too many comments,” she said. “All this makes me very nervous.”

WFAA returned the next day to get more answers.

This time, we brought her a copy of the probate documents from Shifflett’s will.

A court document said she testified in Tarrant County in December about the will. That testimony included verifying specific details about the will and when Shifflett died.

On our second visit, once we showed her the papers showing she had appeared in open court, she acknowledged that she had testified and that she did, in fact, know about the will and the house. She did not explain why she had professed ignorance a day earlier.

“Kathy is my friend of a long time,” she told WFAA.

She told WFAA that she decided she didn’t want the house because it would be too costly to fix it up. She denied having received any money from Shifflett’s estate

“I no needed this house,” Garcia said. “I needed more money.”

Still, Garcia denied signing three documents related to the will.

That included the deed transferring the title of the house into her name. The deed was dated the same day as the will, records show.

She told us she didn’t know who had signed the documents.

“You need es(sic) investigation more,” Garcia told us.

Bonney, the Dallas attorney, also represented Becquer’s mother in the Shifflett probate case. He did not return a request for comment.

Becquer was initially released on $10,000 bond after her arrest in February. However, in early March, prosecutors filed a successful motion seeking to have the bond raised.

The motion said that she was known to travel back and forth to Cuba on a regular basis, “owns several homes with disabled patients who cannot defend themselves” and was found in possession of “several items of contraband upon the search of her homes which was conducted at the same time of her arrest.”

In raising her bond to $750,000, the judge also ordered that she surrender her passport, allow searches of her home and residence at any time, prohibited her from opening new bank accounts of business, forbid her from acting as a “fiduciary or a notary,” and ordered that she surrender her notary stamp and notary book record.

Chris Devendorf told police and WFAA that his brother ended up in one of Becquer’s boarding homes after recuperating from a long stay in the hospital. His brother, Kelly Pankratz, had a degenerative brain condition, a liver issue and developed sepsis while hospitalized.

“She cut everybody off,” Devendorf said. “She would block phone calls.”

He says for months, he could not reach his brother. He called Mansfield police and asked for welfare checks. He and his brother’s friends spoke with Adult Protective Services.

“They were like, ‘Well, what do you want us to do?’” Devendorf said.

He said he asked that his brother be taken out of the house.

“They didn’t do that,” he said. “The system really failed.”

Pankratz died in January. His autopsy is pending.

Both Becquer and Brown operated boarding homes in Grand Prairie.

A Grand Prairie spokeswoman told WFAA that city council members will be asked to approve a boarding home ordinance in the coming months.

Angelique Estes told WFAA she’s doing well. She is now living in another boarding home in Tarrant County.

She told us she didn’t think much can be done to fix the system.

“Laws are too hard to change,” she said. “There’s not enough people to do what we need. It’s just messed up.”