Editor’s Note: U. Renee Hall assumed command of the 3049-member Dallas Police Department on Sept. 5. Hall was born and raised in Detroit. She spent 18 years on the Detroit Police Department. This is the first of several stories introducing WFAA News 8 viewers to Hall.

In a tiny, two-story white frame home on the east side of Detroit, Bonnie Hall raised three children.

One of them was Dallas' future police chief, U. Renee Hall.

“I always knew she was destined for great things,” says her mother, 71.

But it hasn't been easy.

The father of her three children, Ulysses Brown, was killed in the line of duty in 1971. Hall was just six months old. Hers was a life shaped by that early tragedy, by a mother determined to give her children a better life and by her decision to follow in the footsteps of her father.

“Her dad was a hero, and so she was inspired by her dad,” says Detroit Police Chief James Craig. “She felt her dad’s presence was with her every day that she was out to serve and protect.”

Hall family’s history is similar to many other black families in Detroit. Her mother and father’s families left the Deep South during the Great Migration in search of better jobs and to flee oppressive Jim Crow laws.

Bonnie Hall was 19 when she met Detroit police officer Ulysses Brown. He’d served four years in the Army before joining the department in 1967.

In three years, they had three children: Terrea, Ulysses and Renee.

“He was a wonderful man,” Bonnie Hall says. “He loved his kids.”

His life would be cut short at 28 when he was shot and killed during a robbery. Brown was a member of a specialized unit cracking down on prostitution. They never found his killer.

His death left Bonnie Hall with three children under the age of three.

“To me, it wasn't a hard job at all because I had my mom,” Bonnie Hall says. “She was here. We raised them in shifts. She worked days. I worked afternoons. So they were never alone. And with grandma, you can't get away with anything.”

Christian faith and discipline were a daily part of life in the Hall household.

“My mom and grandmother, they made sure we lived according to Biblical principles,” Renee Hall says. “We had to make sure we took care of people, and you treated people with respect and dignity.”

Hall grew up in a white, middle-class neighborhood. The Hall family was one of the first African American families on the block.

But like so many other Detroit neighborhoods, it was changing and not for the better. It suffered as white families fled Detroit and renters moved in.

The lots next to her mother’s home are now vacant. The homes that stood there were long ago demolished.

Hall’s mother worked in a General Motors plant to support them.

“Growing up, she was the busiest mom you've ever seen and she did it so gracefully, without ever a complaint,” Hall says. “I was in cheerleading. My brother was playing football. My sister was playing volleyball. She was everywhere. She was the soccer mom. She did it all.”

The family says they knew early on, Hall was not going to be average.

“Mom said that when she brought her home, she put her on the bed and she lifted her head up and looked around,” her sister says.

“She was just some days old,” her mother adds. “I said, ‘Uh oh, here we go.”

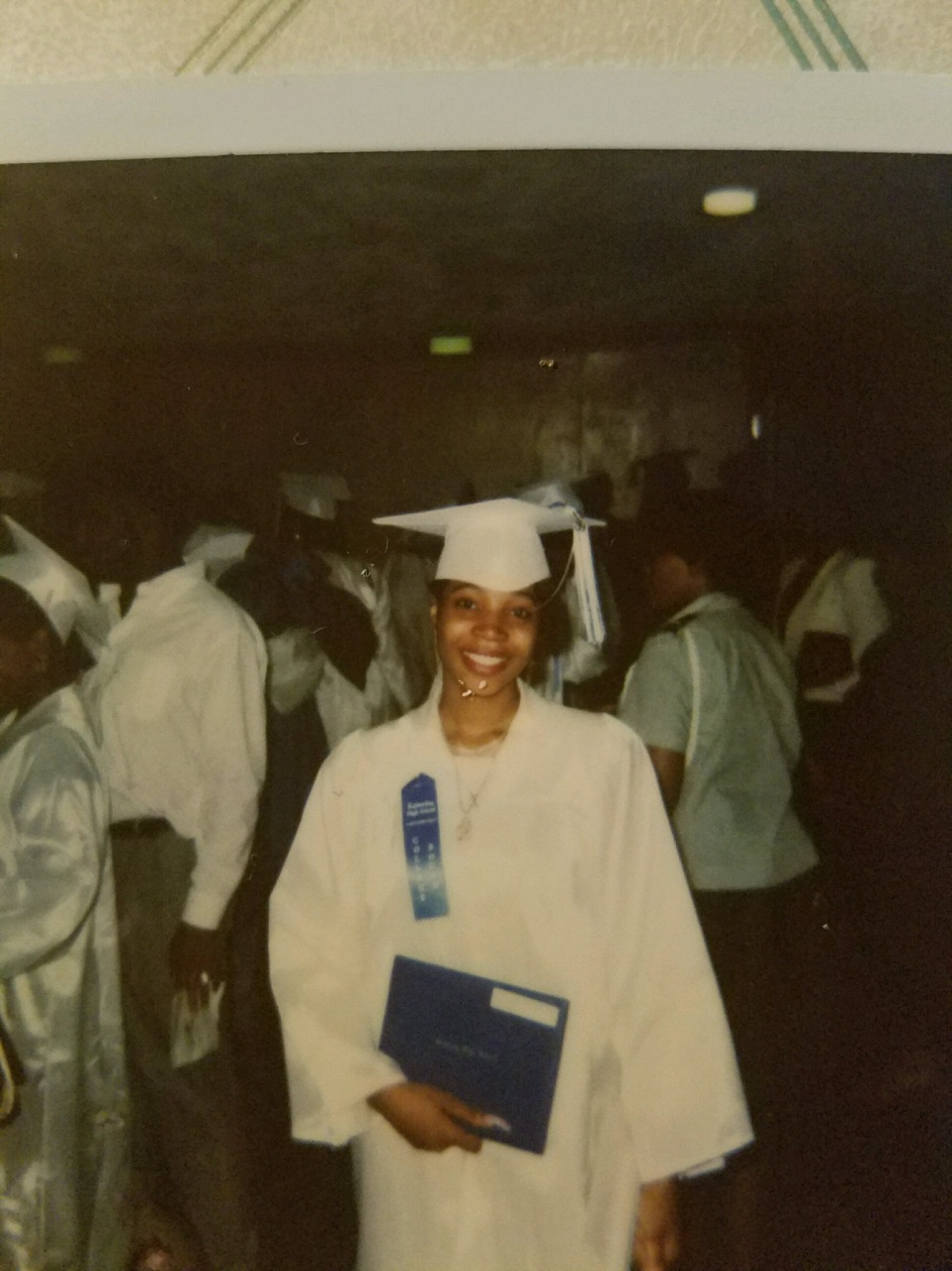

Hall went on to make good grades and be senior class president at Kettering High School.

Hall could at times test her mother’s patience.

When Hall graduated from high school, she came up with a plan to take six months off from school.

“I said, ‘Ok, six months, you don’t have six days,’” her mother says. “You’re going to figure it out before the end of this week because either you’re going to college or you’re out.”

She packed Hall’s clothes to make sure her strong-willed daughter got the point.

Needless to say, that fall, Hall set off for Grambling State University in Louisiana.

“I can remember being home for the summer, and asking her to get me a job in General Motors. They would bring home like $1,500 dollars a week,” Renee Hall says.

Her mother told her no. She told her daughter that if she got accustomed to making that kind of money, she would never return to school. Bonnie was determined her children would be more than factory workers.

Hall graduated with a criminal justice degree. She came back to Detroit in 1994. She planned to become a lawyer.

While in a graduate program at the University of Detroit Mercy, she met the man who would encourage her to consider joining the Detroit police force.

Wayne County Benny Napoleon, one of her professors, was chief of the Detroit police department at the time. He wanted her as one of his officers.

“She had a tough, but solid upbringing like a lot of us,” Napoleon says. “It’s a town that’s always valued people that work hard and people who are honest and down to earth.”

But when Bonnie Hall’s daughter decided to follow in her father's footsteps, that was tough.

The year was 1999 in a city where violence was skyrocketing, and it was becoming known as one of the most violent cities in America. Hall was 29 years old, just a year older than when her dad died.

“She was not happy,” Renee Hall recalls, chuckling at the memory of her mother’s reaction.

Her mother would spend many days and nights praying for the safety of the daughter who had now followed in the path of her father.

“I said, ‘Oh my God, if something happens to her, I don’t know if I can go through that,’” her mother says.

Daran Carey was one of Hall’s first sergeants. They worked together in the community policing division early in Hall’s career.

“When I first met Chief Hall, I thought one day, this girl’s going to be the chief of police somewhere,” he says. “She always had her stuff together.”

As Hall moved through the ranks, she built a reputation as firm and disciplined while at the same time, being understanding and down-to-earth. She’s a strong proponent of community policing and regarded as a commander who cares about the needs of her officers.

“I’ve always said Chief Hall leads by example,” Carey says. “Whatever she wants her officers to do, she’s going to do it.”

Even more than a decade later, one crime scene still sticks with Hall. She and a group of officers had responded to a report of a hysterical naked woman.

Inside a house, she and her partner found blood and brain matter spattered on the wall, a bloody pipe wrapped in a child’s pink coat and a dead woman. The bodies of four children, the youngest being nine years old, were found bound and beaten to death in a bedroom.

The woman’s ex-boyfriend was arrested after fleeing the scene.

“It was one of the most horrific things I had ever seen,” she says. “At that point, I knew policing was real. It was the reality that there are people that are capable of taking a life with no remorse.”

For Hall, her Christian faith is a big part of who she is. She served as a leader and teacher in a large Detroit church. That faith helps her deal with with the evil she sometimes encounters on the job.

“This job can be very thankless,” Hall says. “It can be mean and cruel at times. I center myself in God.”

Craig met Hall at a policing conference before he became Detroit police chief. Then chief in Cincinnati, he remembers thinking she was sharp and understood “effective policing.”

So when he took over the troubled Detroit police force in 2013, he made her a key part of his turnaround effort.

At the time, crime was still skyrocketing. The city was in bankruptcy. Police were taking pay and pension cuts. The city was under a consent decree and officers were leaving in droves.

“The community had lost confidence in its police department, so it should be no surprise that coming in the door, significant change needed to be made and it needed to be made quickly,” Craig says. “Chief Hall was on the front row of that change.”

Hall rose quickly through the ranks over the last four years. She went from a lieutenant acting as a precinct commander to deputy chief.

These days, things are far from perfect in Detroit, but headed in the right direction. The consent decree was lifted a year after Craig became chief. Crime is still too high but down significantly.

“When I told her, I said, ‘Mom, I think I'm going to apply for Dallas. I've been encouraged to apply for Dallas,’” Hall says. “She looked up at the sky. She said, ‘That's your job, you're going to be the Dallas police chief’ and she walked in the kitchen and made herself a cup of coffee and I said, ‘Well, that's that.’”

At a reception last month, many of Detroit’s finest, community leaders and city officials gathered to say goodbye to Hall. They were proud that one of Detroit’s own was becoming Dallas’ top cop.

Her mother beamed in a table at the front of the banquet hall overlooking Tiger Stadium. The pastor of her church sat beside Hall and offered a prayer for her success in Dallas.

“This is truly an exciting day for the city of Detroit,” Craig told the crowd.

Back at the Hall house, there was an easy camaraderie between mother and daughters.

They bantered about when Bonnie Hall might be coming to Dallas.

“I’m coming; I’m not going to say when,” Bonnie Hall says. “She told me if I come, she’s kidnapping me.”

Hall joked there’s nothing on the books about kidnapping one’s parents being against the law.

“I’m reluctant to go because I might not get back,” her mother replies, laughing.

Bonnie Hall has lived here for 47 years, staying after so many of her neighbors moved away. She is so proud of the three children she raised.

Hall’s brother, Ulysses, is a chief warrant officer in the Navy. Her sister is a long-time kindergarten teacher. And of course, her youngest is now chief of police of one of the largest police departments in the country.

“They all turned out so good,” she says.

In so many ways, Hall reminds her mother of the father who died so long ago.

He was a go-getter, she says. He was unafraid to speak his mind. “He wasn’t standing for any nonsense,” Bonnie Hall says.

One thing Bonnie Hall knows for certain is that Hall’s father would be so proud of his daughter.

“I would love to think that he’s standing right by her I really would,” she says.