DALLAS — Who killed Jean-Claude Pratts and dumped his body on the side of the road in a field in Oak Cliff?

His family and friends are desperately seeking answers.

They can’t understand how the 33-year-old marketing professional and Afghan War veteran living in downtown Dallas ended up in that field.

“It's bad not knowing,” said his uncle, Tony Millsap, from his home in DeSoto. “It makes it harder to grieve and move on because you don't know. And not knowing is bad enough, but having people not care is even worse.”

Jean-Claude was No. 46 in the city’s murder toll. Seventy people have been murdered thus far – three in the past week.

Two days after our last piece aired, Dallas police made reference on its Facebook page about our series.

The post, titled “Protecting Dallas,” said “some media outlets” were seeking to “fill the news cycle sensationalizing some murder cases and ignoring others ... Although there has been a rise in crime this year over last year, people in Dallas are safer now that they have been in over 50 years.”

It seems they missed the point.

The idea behind “Dying in Dallas” is to put faces to names to really give voice to the victims who have been murdered in our city. So, let me tell you about Jean-Claude.

Like so many other murder victims in Dallas, Jean-Claude is black. He's not a gang member, a drug dealer or a criminal. There was nothing to explain why this happened.

His story begins far away from the field where he was found.

He is a Slidell native. He has a twin sister, English. His family called him, “J.C.” or “Claude.” He was senior class president and Mr. Northshore at Northshore High School. He served in the Louisiana Air National Guard and studied physics at Dillard University. He served in Afghanistan in 2004.

He moved to San Antonio about 10 years ago. There he met my colleague, Demond Fernandez.

They were members of a group of young black professional men. They called themselves, “The Crew.”

“We would have Sunday potlucks and Jean-Claude was famous for bringing his Cajun dishes from Louisiana,” Demond says. “He was one of those guys you could definitely call the life of the party.”

Jean-Claude was a real go-getter, a guy always on the move, constantly networking.

He helped Demond find his first apartment in Dallas. They were neighbors for a time.

“He was just one of those guys who tried to make everyone’s life easier,” Demond says.

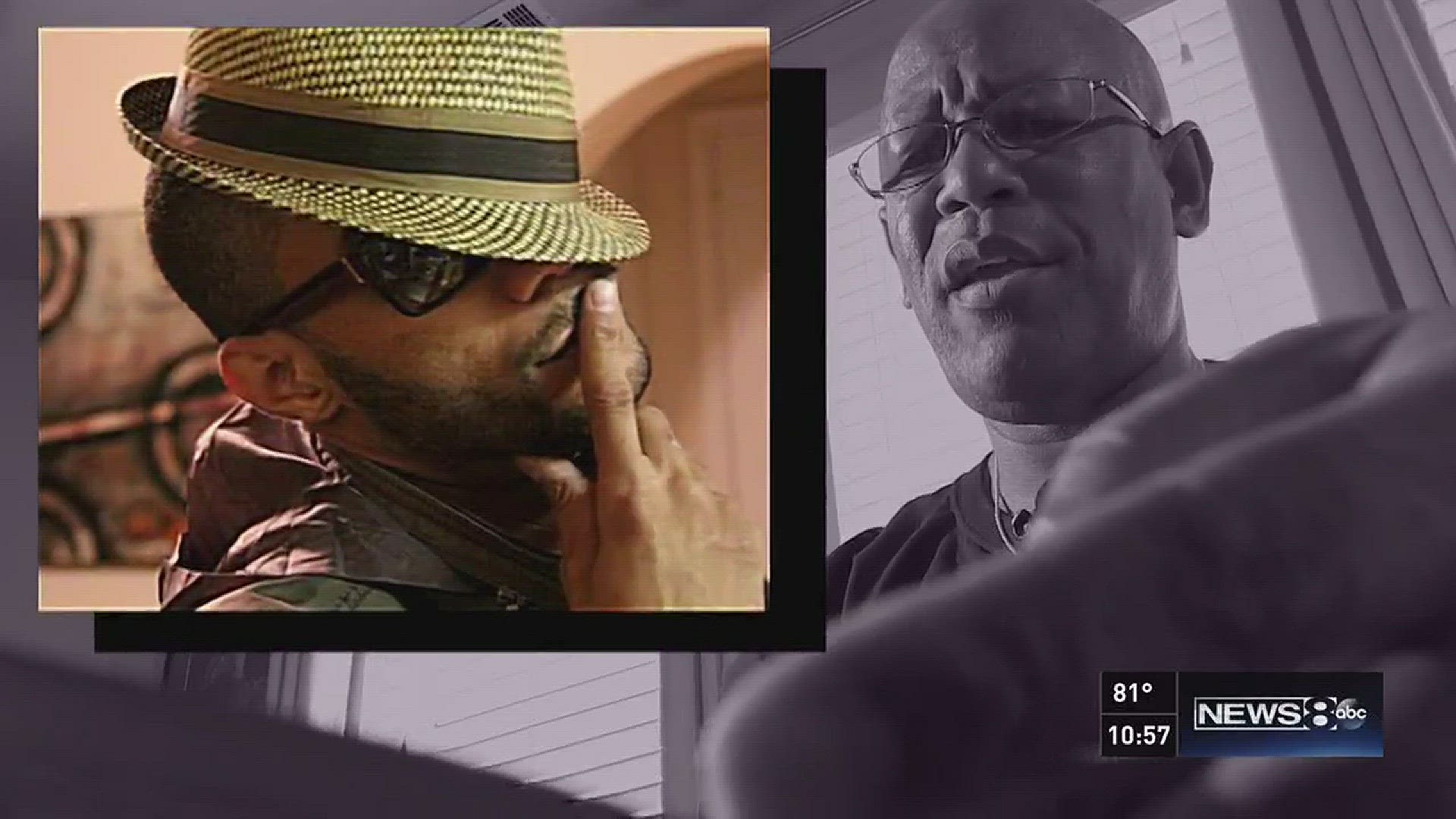

Pictures of Jean-Claude show his exuberance and zest for life. In one photo, he’s standing beside the ocean, his arms held wide as if to say the world was his to conquer.

“He was a handsome guy, a dapper guy,” his uncle says. “He wanted to be successful. He wanted to have everything. He wanted to make a mark on the world and to have the world know, ‘Hey, I’m Jean-Claude and I was here and when I’m gone, y’all gonna miss me.’”

On April 4, 2016, a passerby-spotted Jean-Claude’s body on the side of Kolloch Drive, a remote area in Oak Cliff not accessible from the freeway. He had been shot in the head. His cellphone, an item he was never without in life, was missing.

When Demond saw the alert on DPD’s Twitter feed announcing his friend's death, he had to do a double take. It couldn’t be his friend.

“I was shocked, especially when they said his body was found in Oak Cliff,” he says. "We live downtown and I didn’t know Jean-Claude to frequent Oak Cliff.”

Millsap and his wife were the first in the family to learn of his death. Police came to their house to tell them.

They’d just seen him Easter Sunday. His mom was in town and they’d had a family dinner.

The day before he died, Jean-Claude called asking them if he wanted to attend an arts festival. They couldn’t go. They will forever regret not attending.

“He loved life and it just makes me angry that someone took his life," said Millsap as he held his nephew's funeral program. "You can take anything he got. You can give it back if you can get it again, but not his life.”

His uncle is upset that Jean-Claude’s death passed largely unnoticed outside his circle of friends and family.

“We saw a little bit online, and nothing really in the paper," Millsap said. "So it just falls through the cracks. Just add it up. There’s another young black man who died so they probably just wrote it off as some kind of drug deal or whatever. Just because a black man dies in a violent way, he’s not complicit in his death. His life has to have enough worth to us to find out what happened.”

His uncle went to DPD’s blog and looked at the homicides that occurred since the start of the year. He was struck by how many of the victims were black and male and the cases unsolved.

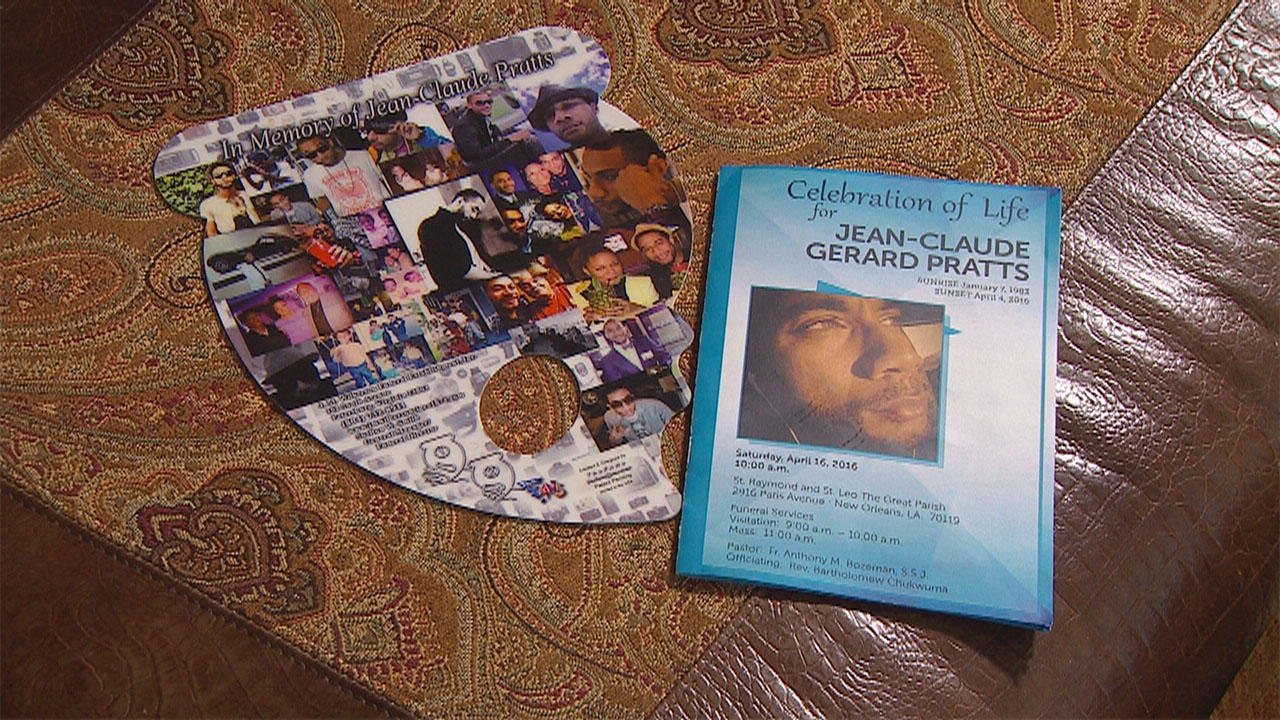

Jean-Claude’s funeral was fittingly New Orleans style.

A brass band played. A carriage with white horses carried his casket. His family wore loud, bright colors. They danced in the streets.

“Jean-Claude would have wanted it that way,” Millsap says.

For Jean-Claude’s wider circle of friends, it’s left many with lots of questions but no answers.

“Everyone’s still talking about it because we just can’t believe not only that he’s gone, but that he was murdered,” Demond said. “Just knowing the type of guy that Jean-Claude was, somebody knows something. That’s the thing that is so disturbing right now. It would bring peace of mind if we just put the pieces of this puzzle together."

My photographer and I went with Millsap to the place where Jean-Claude was found.

He had last been there shortly after his nephew’s death. He told me he went there hoping to make some sense of it.

But when he saw it, it made no sense because he knew it was not a place that Jean-Claude would be in.

“How did he get here?” his uncle said.

Based on what police have told him, he believes Jean-Claude was killed elsewhere and dumped there.

“This is farmland," Millsap said on the drive to the location. "This is country. This is nowhere that Jean-Claude would have been in life.”

When we got out there, it took us a few minutes to find the exact spot. Millsap was the first to notice the tiny swath of crime scene tape still wrapped around a tree – the only visible reminder of where Jean-Claude was found.

Millsap took a small piece of it, saying, “'Do not kill,' maybe, that’s what it should have said. A line do not cross.”

“I just hate to think that they treated him like trash,” he told me. “I mean, coming down here you saw an old mattress and an old couch and some other junk that’s lying on the side of the road, and to think they treated my nephew like that somebody treats an old mattress, it hurts.”

I printed out a large photo of Jean-Claude to take with us out there. It’s a picture of a smiling Jean-Claude dressed in a suit, looking every bit the professional that he was.

“We shouldn’t be here,” he says. “When I look at that picture, we shouldn’t be here. He shouldn’t have been here.”