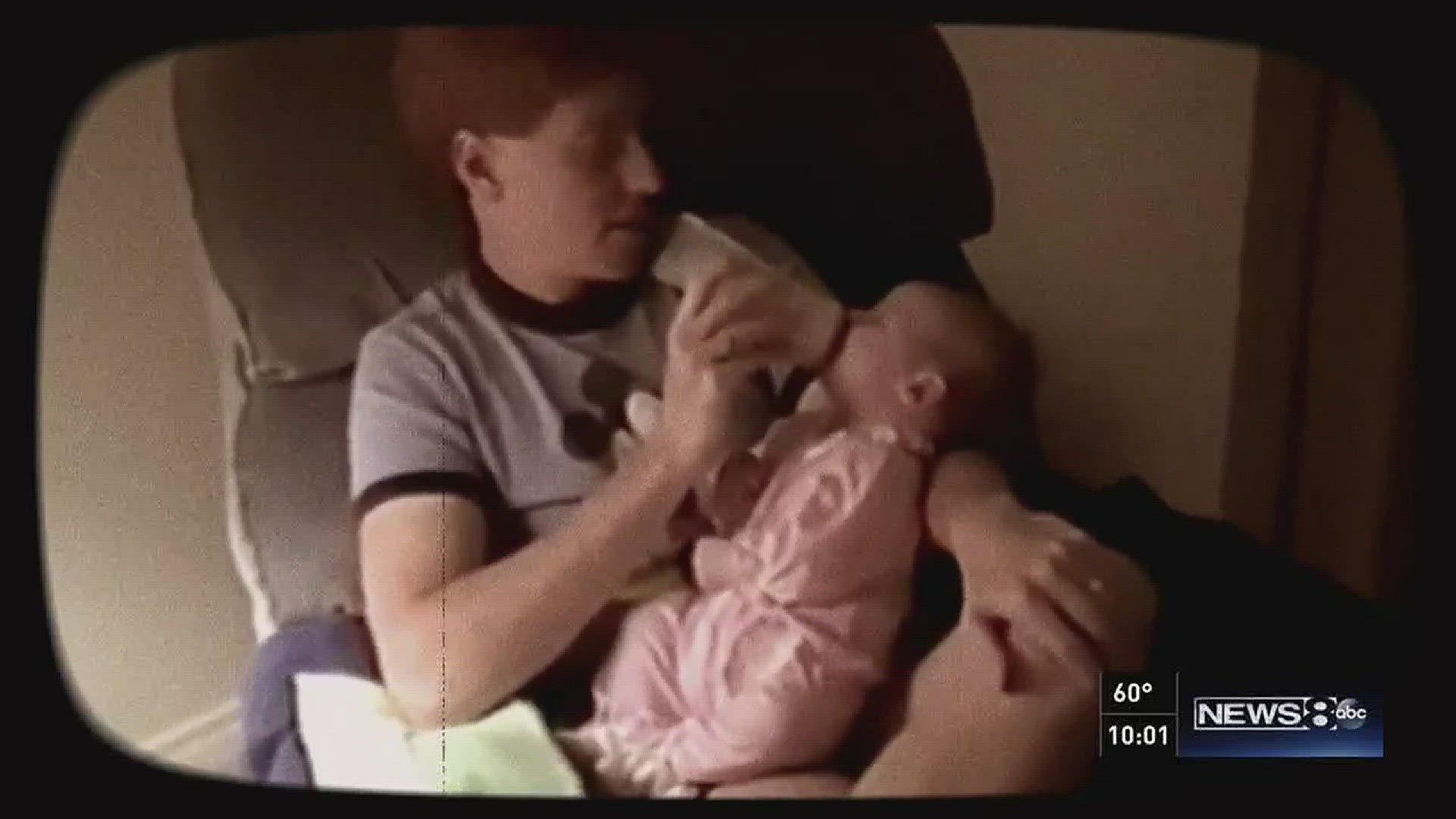

DALLAS -- In home movies, Tony Crawford is the smiling redhead building a backyard fence, doting on his infant daughter and pushing the toddler around in her baby car.

He and his young wife were completely unaware that their lives were about to change forever.

“I have told people one day he left for work and could walk and then he couldn't,” says Patricia Crawford, his wife.

It was 25 years ago this month when Dallas police patrol Sgt. Tony Crawford, then 31, answered what appeared to be a routine call. He’d been on the force for nine years.

Two suspicious teens were pushing a bike through the neighborhood behind Lakewood Elementary. They had run away from a youth center near Georgetown. The worst thing they’d done up to that point was skip school.

The boys, 15-year-old Brad Ehly and 14-year-old Jeramy Dillingham, had a stolen gun.

“Brad told Jeramy if he stops to talk to us, if it looks like we’re going to jail, you divert his attention and I’ll kill him,” Crawford said.

As Crawford patted down Dillingham, Brad pulled the gun and aimed it at his head. Crawford saw the gun and pushed it away just in time as it fired.

Ehly twice tried to shoot him in the chest, but it didn’t fire. Dillingham ran away as they struggled.

“I finally shoved him as hard as I could and I was going to dive behind a pole that was behind me and take cover,” he says. “When I turned my back to dive, he pulled the trigger.”

The bullet went under his vest, traveled over his kidney and severed his spine.

“The minute the bullet impacted my spine I knew I was paralyzed,” he recalls.

As he lay bleeding on the ground, Crawford says he felt the gun in his ear as Ehly repeatedly tried to fire the gun. He then tried to shoot Crawford with his own gun.

Dillingham returned and tried to pull Ehly him off.

“Brad got so enraged about his gun not working that he started beating me over the head with it,” Crawford says. “He knocked out a bunch of teeth and gave me a skull fracture.”

Crawford begged Ehly not to kill him.

“I was trying to reach for a picture that I carried of my daughter in my pocket to show them, 'Hey, you're fixing to widow my wife and orphan my child,' but they ran away and left me there in the gutter,” he said.

Patrick was at home when officers knocked at the door. Fifteen-month-old Meredith was in the bathtub.

“I saw two of them standing there I knew that he was dead," she said. "That was one of the first things I said was, 'Is he dead?"

That night, Dallas Police Chief Bill Rathburn came to Crawford's hospital room. Crawford says Rathburn told him not to worry about his job, that there would be a job waiting for him when he could return to work.

Before then, an officer in that situation wouldn't have kept his badge and Crawford would have been forced to take a disability pension.

“I knew a disability pension wouldn’t cover it,” he said. “I was only 31 years old and I was facing life from a wheelchair.”

These days, six percent of the force is reserved for officers who can't return to full duty.

“Not being a part of that would have been a heartbreaking for me so be able to go to work, still able to wear a uniform and still able to be to help people and still be known just as a police officer, but a Dallas police officer was very important,” he said. “I can’t thank Chief Rathburn enough for what he did.”

Two weeks after the shooting, Crawford would speak to the media. He still had a bruise under his eye.

“I’ve told everybody I’m not rolling out of here,” he said. “I’m walking out of here.”

It was not to be. He would not never walk again. The bullet remains lodged in his body. He has no feeling below his waist.

Crawford spent three months in rehab, learning to live life in a wheelchair.

“You learn to do things differently,” he said. “I actually taught my daughter to ride a bike. We figured a way.”

When all he wanted to do was sleep and sit in a recliner, she made it clear that that wouldn't work.

“After about three weeks of that, she bought me a 3x5 card and said, 'So we don’t have a fight about this, these are the things you will start doing for yourself,'” he said. “I knew right away she wasn’t going to let me sit around and feel sorry for myself.”

Patricia says the nurses had spoiled him.

“I had to say this is what the real world is going to be like and you’re going to help me,” she said. “I think we were so young and we had a young daughter and we just didn’t dwell on it you know we just had to live life.”

Meredith, now 26, grew up riding on her dad's lap.

“I just remember that he was always there,” Meredith said.

He was at every game and every recital. She never knew a time when he wasn’t in a wheelchair.

“We’d watch old baby videos and there’d be a video of dad walking by or carrying me and I’d look at him and think what’s wrong with dad,” she said. “A wheelchair was all I knew.”

Ehly and Dillingham were certified to stand trial as adults.

Ehly stood trial and was convicted of attempted capital murder. He received a life sentence. Dillingham pled guilty to aggravated assaulted and served 10 years.

Meredith is just grateful that her dad didn't die on that brisk November night all those years ago.

“I don’t really think about what Brad did," she said. "I think about what my dad did and he chose to live and chose to move forward,” she said. “And no matter what a young man chose to do with hatred in his heart on a night in November, my dad he chose to live. He chose so much more and didn’t let him take anything away from him so I’m so proud.”

Crawford was promoted to lieutenant in 2006. He never let the wheelchair define him.

“We didn't let the disability get in the way of having as normal a life as possible,” Crawford said.

Crawford has forgiven the man who put him in that chair.

Ehly is still serving a life sentence. The parole board has repeatedly rejected his requests for parole. He’s up for review again in June 2018.

"I couldn't ask for more, more blessings you know, “ Crawford said. “I try to look at everything in a positive way. What I've got. What I don't have has never replaced what I do have.”

The Crawfords, who met as teens in Wichita Falls, have been married for 33 years. He says when Patricia said for better for worse, she truly meant it.

He will retire this January with 34 years on the force.

“He's going to miss it. He's ready but he loves what he does,” his wife says.

He says he’ll miss putting on that uniform.

“I wouldn’t change a thing,” Crawford said. “It’s been a great career. Of course, getting shot was no fun, but it’s part of the risk you take. It’s been a great 34 years.”

And that picture of baby Meredith he had in his pocket on that fateful night, he laminated it and kept it tucked in his pocket right next to his heart.