On July 7, 2016, a 25-year-old Army reservist fatally shot five Dallas officers as they escorted protesters during a Black Lives Matter protest in downtown.

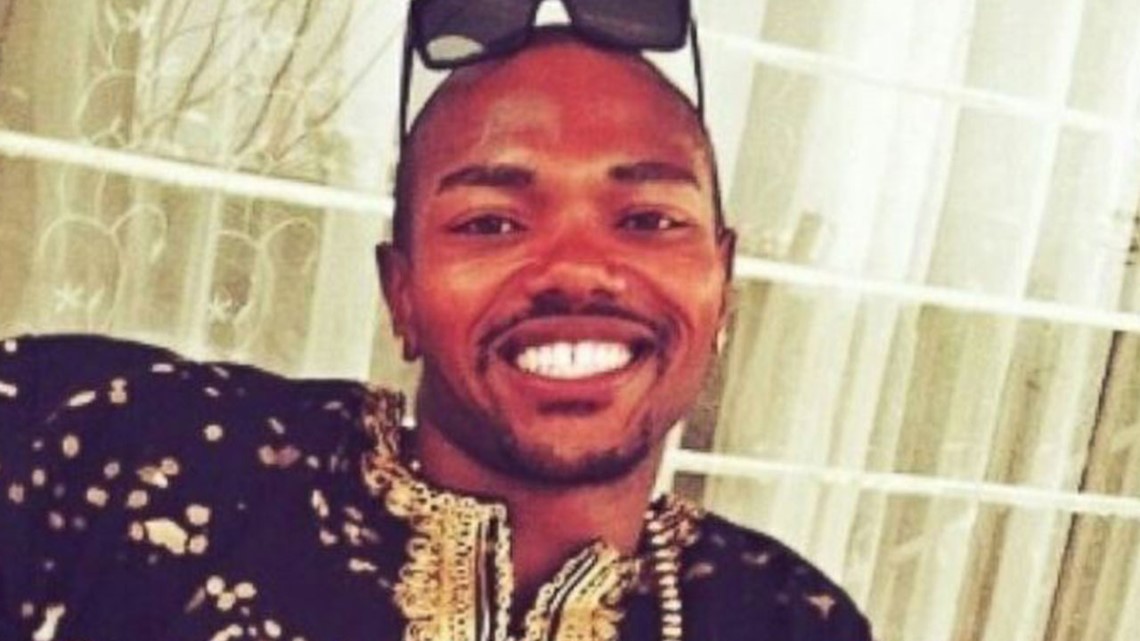

But that night wasn’t the first time Micah Johnson showed signs of aggression and mental health problems.

Prior to the sounds of gunshots ringing out on July 7, the march was peaceful. While video and pictures from other protests across the country showed tension between officers and protesters, the atmosphere in downtown Dallas was different that night. Dallas police showed up in their normal patrol attire rather than armed in heavy gear. As crowds chanted, “no justice, no peace,” officers took pictures with protesters and posted them to their official social sites.

- Click here to read about PTSD treatments, research.

This is what made the deadly violence that broke out as the protest began to wrap up even more shocking. It seemed to come out of nowhere.

The shooter was later identified as Micah Johnson, a Mesquite resident with a past of disturbing behavior.

Then-Dallas Police Chief David Brown later announced Johnson wasn’t officially connected with the Black Lives Matter movement or any terrorist organizations. Not long after, Black Lives Matter reacted on social media: “#BlackLivesMatter advocates dignity, justice and freedom. Not murder.”

A HISTORY OF DISTURBING BEHAVIOR AND SYMPTOMS OF PTSD

So what led Johnson to arm himself that night and aim his gun at police officers? We may never know the full answer to that question.

What we do know is that on that fateful night, during a standoff with police in a parking garage, before he was killed by an explosive, Johnson expressed frustration with police violence.

"… He was upset about the recent police shootings” and “wanted to kill white people, especially white officers,” said former Dallas police Chief David Brown of what Johnson said to officers during his final hours.

But there were signs before July 7 that Johnson was unstable. In fact, he sought treatment for PTSD symptoms.

Deployed to Afghanistan in 2013, he was later accused of sexual harassment and sent back to the U.S. in September 2014. In a report filed by Bradford Glendening, the harassment victim requested Johnson receive “mental help,” according to a New York Times article.

An Associated Press article revealed that a file on Johnson reported he showed signs of post-traumatic stress disorder after his return to Texas and sought treatment for “anxiety, depression and hallucinations.”

“Micah Johnson told doctors he experienced nightmares after witnessing fellow soldiers getting blown in half and said he heard voices and mortars exploding, according to the documents obtained by the Associated Press under the Freedom of Information Act.”

The article also revealed that police were once called to a North Texas Wal-Mart, “where there was an unspecified conflict that required police response.”

According to the file, doctors concluded that Johnson wasn’t "acutely at risk for harm to self or others.”

But Johnson’s mother said he was different when he returned home after his service, stated a report from TheBlaze. Family members said he holed himself up at home. And according to a New York Times report, neighbors reported seeing Johnson “doing militarylike exercises in his backyard" in the weeks before the ambush.

NOT ALONE

Johnson is not the first or last perpetrator of deadly violence to show prior mental health problems.

While there has been no confirmed link of PTSD to the Dallas ambush attack, the National Academy of Science reports that the disorder is “one of the signature injuries of the U.S. conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq.”

Just 10 days after the Dallas ambush, another military veteran fatally shot three officers in Baton Rouge, La.

A former Marine, Gavin Eugene Long fired the deadly shots on his 29th birthday. Much like Johnson, he showed symptoms of PTSD prior to the ambush and expressed anger over police violence.

“I know I will be vilified by the media & police," he wrote in a note found after he was killed during the ambush. "Unfortunately, I see my actions as a necessary evil that I do not wish to partake in, nor do I enjoy partaking in. But must partake in, in order to create substantial change within America’s police force, and judicial system.”

Long served in Iraq for seven months in 2008 and 2009. He was discharged as a sergeant in 2010.

According to a CNN report, Long “told friends and relatives that he suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder.”

And again, Long is not alone:

• May 29, 2016 in Houston, Texas: Army vet Dionisio Garza III, who served seven tours of duty, targeted police in a shooting rampage, killing one civilian and injuring six others before he was killed by police.

• April 2, 2014 in Fort Hood, Texas: Ivan Lopez, who served in Iraq, killed himself after shooting four dead.

• February 2, 2013 in Chalk Mountain, Texas: Marine Eddie Ray Routh shot dead 35-year-old Chad Littlefield and 38-year-old Chris Kyle, who was helping the vet who showed disturbing symptoms of PTSD.

SEEKING PTSD/MENTAL HEALTH TREATMENT

The hard question remains, how do those suffering mental health problems, including PTSD, heal? And how do those around them help?

It’s a complicated and much-debated, researched subject.

In a WFAA article posted just days after the Dallas ambush, Marianne Horne, a counselor who works with veterans, said much of the problem comes from the training and readjusting of when they come back home.

"When they go into the military the military tears them down and breaks them apart and then rebuilds them into soldiers, killing machines,” she said. “If they don't get the right kind of treatment, the right kind of counseling they are going to have problems.”

She also noted another unfortunate fact. Most vets suffering mental health problems don’t get help until a run-in with authorities.

The National Center for PTSD calls cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) the “most effective type of counseling” for the disorder. The site says during CBT, “your therapist helps you understand and change how you think about your trauma and its aftermath. Your goal is to understand how certain thoughts about your trauma cause you stress and make your symptoms worse.”

Others suffering from PTSD have found help through online social groups and in-person group therapies.

Many other PTSD patients are treated with selective serotine reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), a type of antidepressant. However, as the problem persists, research into PTSD treatments continue.

MORE RESEARCH/NON-TRADITIONAL TREATMENTS

In 2012, Dr. Alina Suris, chief of psychology at VA North Texas Health Care System in Dallas, won an award for her research, which delves into the possibility that erasing fears from the minds of patients could cure vets.

More research is looking into psychedelics and ketamine as potential treatments for PTSD.

In a statement from UT Southwestern, ketamine, a synthetic compound used as an anesthetic and analgesic drug, is used by doctors when anti-depressants don’t work.

“If taken with proper medical care, ketamine may help severely depressed or suicidal patients in need of a quick, effective treatment,” said Dr. Lisa Monteggia, a professor of neuroscience at UT Southwestern’s O’Donnell Brain Institute.

Monteggia said while there’s a high demand for the treatment, she’s researching “the questions we still have about” the drug.

“How often can you have an infusion?” she said. “How long can it last? There are a lot of aspects regarding how ketamine acts that are still unclear.”

In November of 2016, the Federal and Drug Administration gave permission for large-scale clinical trials involving MDMA, also known as Ecstasy. In a New York Times article, a veteran who served three tours in Iraq and Afghanistan said MDMA changed his life. He was part of an early drug trial.

And as research continues, others have turned to yoga and meditation to ease their minds. Once such program is called Warriors at Ease. The program has “Ease-trained teachers” accessible across the country for yoga and meditation specialized for the military community, including spouses and other family members.