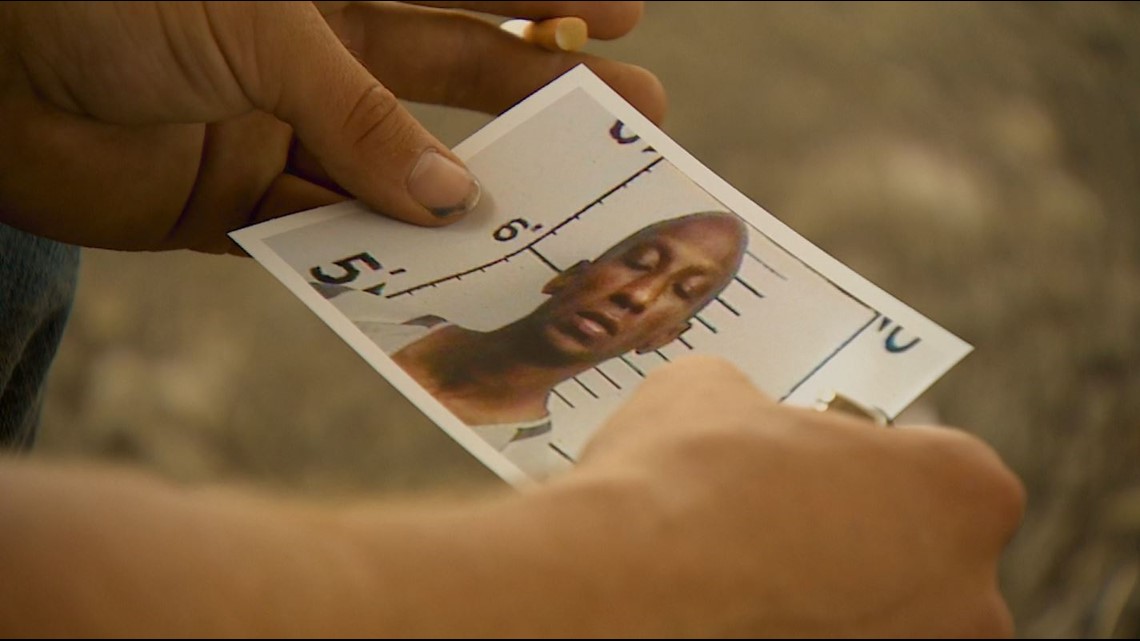

JOHNSON COUNTY, Texas — A few days after Greg McElvy died in the Johnson County jail, the then-sheriff announced that officials believed he’d swallowed a bag of drugs and died.

But a WFAA investigation found the truth behind the 35-year-old’s death was more complicated and disturbing.

Over the course of three days in 2013, McElvy repeatedly told guards working for LaSalle Corrections, the company that runs the jail, that he thought he was dying. He was vomiting. He could not control his bodily functions. He wasn’t eating. He wasn’t drinking. By the end of that three days, he collapsed in a pool of vomit.

Two dozen inmates were so appalled by what they witnessed they wrote statements describing McElvy’s descent to death. Those statements, obtained through the state open records act, describe jailers’ apathy and indifference.

“He begged for help,” said Jonathan Oliver, who was in jail at the same time on a probation violation and wrote one of those statements. “He needed help and they didn't give it to him.”

An autopsy found McElvy died not from swallowing drugs, but from “bronchopneumonia” complicated by asthma. Heroin withdrawal was listed as a secondary cause.

WFAA began digging into McElvy’s 2013 death more than a year ago as part of an investigation into deaths in jails run by LaSalle Corrections. The Louisiana-based company runs the Johnson County jail, as well as jails in Fannin, McClennan, Bowie and Parker counties. The company has been repeatedly cited by the Texas Jail Standards Commission for problems in its jails. The company recently announced it was ending its contract to run a jail in McClennan County after it repeatedly failed jail standards inspections.

The WFAA investigation found that over and over, prisoners – not convicted of crimes – have died in the company’s jails under questionable circumstances. Guards and medical staff in some cases refused to help them. Guards have been repeatedly caught falsifying jail checks in cases that involved the deaths of prisoners.

RELATED: Jailed to death: He repeatedly asked for a doctor. Guards pepper-sprayed, beat and cuffed him.

McElvy’s 17-year-old daughter and his parents filed a federal civil rights lawsuit in May. The statute of limitations on those types of cases is two years. However, because McElvy’s daughter is not yet 18, a lawsuit can still be filed on her behalf.

The lawsuit also argues the standard statute of limitations on McElvy’s parents should also be waived because his parents were falsely told by LaSalle representatives that he died of a heroin overdose. His parents did not become aware until late 2018 of the true circumstances of their son’s death, the lawsuit said.

“This was totally avoidable,” said Emil Lippe, an attorney representing the family. “His life could have been saved.”

The arrest

McElvy, 35, was arrested just before midnight on Sept. 13, 2013 on a shoplifting charge. He had told the jail’s medical staff that he had a history of asthma and difficulty breathing. He seemed OK initially.

He saw a nurse the following morning. He said he had asthma and was a heroin user, that he was having withdrawals. She told him she could not give him the withdrawal medications because his blood pressure was too low. He was given an inhaler for his asthma.

As the day progressed, McElvy complained he wasn’t feeling well.

He filled out a medical request asking for help. He wrote “EMERGENCY” across the top of it. He wrote he was having “heroin withdrawals” and couldn’t breathe.

Statements from the inmates, who were housed in a dorm with McElvy, describe in detail how McElvy’s condition rapidly deteriorated.

“For the last two days, the sick black man has begged for medical attention and has not really received any,” prisoner Barborino Salazar wrote.

Inmates said McElvy kept hitting an intercom button asking the guard in the picket, or control room, to get help. He said he was having an asthma attack. Meanwhile, McElvy repeatedly urinated and defecated on himself.

“The lady in the picket told him if he pushed the button again that she would write him up,” Christopher Shearer, another of the prisoners, wrote.

‘Showed no compassion’

The inmates said she laughed at him and made light of the situation. Prisoner James Warton wrote that the guard “showed no compassion and said you’re just gonna have to deal with it. The inmate kept throwing up and there were no signs of any kind of faking.”

The guard “only laughed at him” as he told her he was dying, wrote Jason Nick, who was in jail at the time. He wrote that she said, “’He’s a grown man. He needs to learn how to use the restroom.’”

“She only yelled at him that if he said anything else, she would write him up,” Nick wrote.

Jail supervisors were aware of McElvy’s predicament, records and interviews show.

A jail sergeant told investigators she received a call from a guard reporting that inmates in the dorm were in an uproar about McElvy. Several jail trustees were pushing the guard intercom button demanding medical attention for him, investigative records show.

A lieutenant told investigators he was called down to the dorm to check on McElvy. He said McElvy asked why medical had not responded to his written request for help. A nurse – different than the one who saw McElvy earlier in jail – told the lieutenant that there “was nothing else she could do for the inmate because he was detoxing and he had already been given his meds,” according to the investigative report.

Investigators later found, however, that the initial nurse who saw McElvy determined he could not have detox medication because of low blood pressure.

One guard helped

Prisoners say one of the guards did try to help McElvy. Her name is Danielle Kacho.

Kacho told investigators and WFAA that McElvy’s second night at the jail, he repeatedly told her was dying. He said he was having an asthma attack. Kacho asked for a nurse to look in on McElvy. When the nurse came around midnight, she did not check his vitals or his chart. According to LaSalle records, she wrongly “assumed” that he was already on medications for withdrawals.

Kacho asked the nurse to move him to the infirmary. The nurse said she would see what she could do. McElvy was never moved to the infirmary, where he would have been checked on every 15 minutes.

“I don’t believe this man should have died,” Kacho told WFAA in an interview. “I can’t stress enough that he should have been in the infirmary.”

Because jail staff did not move McElvy to the infirmary, the inmates felt they had to step in and care for him themselves, interviews and investigative documents show.

On the day he died, McElvy did not get up to eat. Other inmates tried to get McElvy to eat, but it only made him sicker. He fell off his bunk and began puking, Oliver wrote.

Just before he collapsed, McElvy again went to the guard control center and pleaded for help. She told him to stop. Warton wrote that McElvy threw up and then collapsed. Inmates began beating on the window and yelling for help.

“We caused a ruckus and almost started a riot,” Oliver told WFAA.

After McElvy collapsed, an ambulance was summoned. McElvy died less than an hour later at a local hospital.

Several of the inmates wrote that the guard who had laughed at and mocked him should be criminally charged.

“What I saw from the last two nights was pure negligence,” Teodoro Gonzalez, another of the prisoners, wrote.

No criminal misconduct

The Texas Rangers report, however, cleared the guard who inmates say ignored McElvy’s pleas for help of criminal misconduct. The report said that “while the perception may have appeared” the guard ignored McElvy’s pleas, “the findings of this investigation would indicate” the guard “did make the appropriate contacts.”

The second nurse who had assumed he was on withdrawal medications resigned in lieu of termination the day after his death, according to company records. The records state she “failed to follow policy and procedure for withdrawal protocol guidelines.”

McElvy’s death still haunts Oliver, the former prisoner.

“I remember that guy’s name like it was yesterday,” he said. “We wrote his name on the bunk he was sleeping in. We were all messed up about it.”

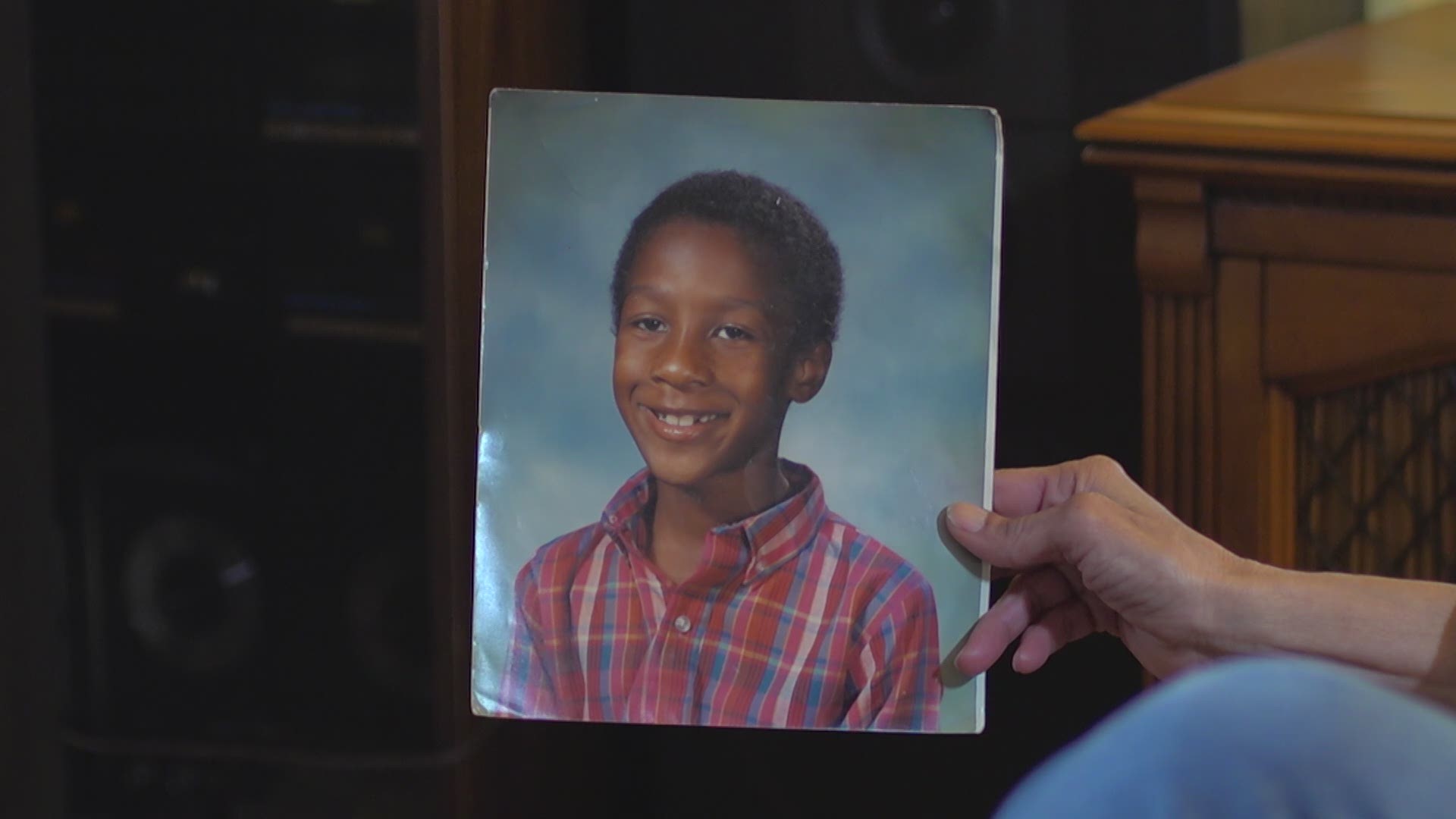

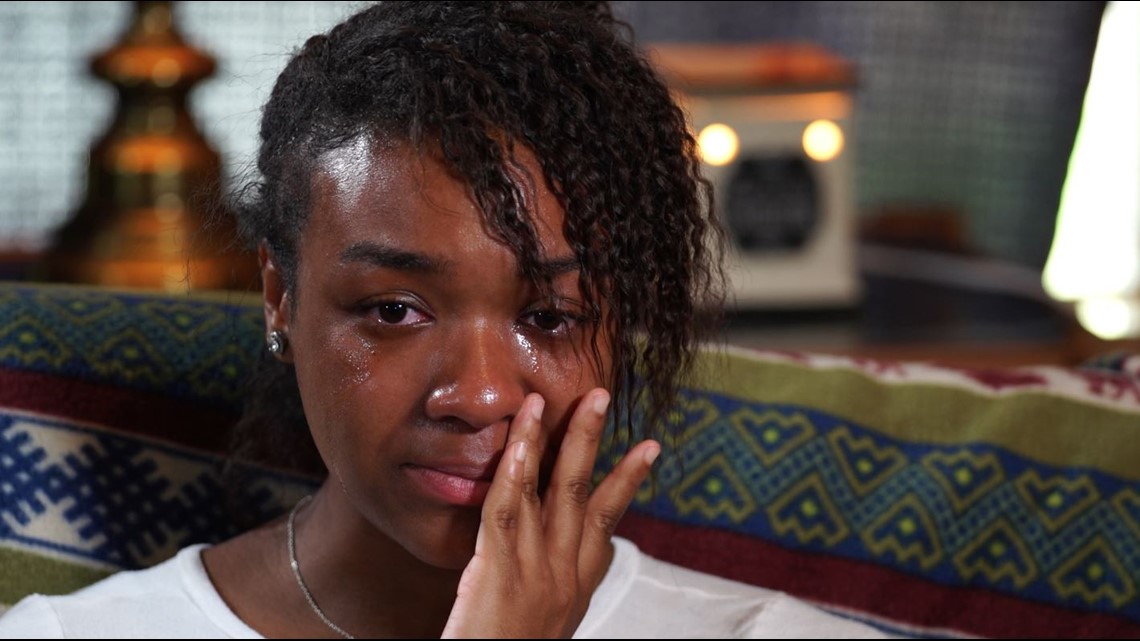

Six years after his death, McElvy’s family still mourns what could have been. His daughter, Kyra, was 11 when he died.

Tamela Wimberly, Kyra’s mother, named off all the milestones McElvy has missed in his daughter’s life. “I think he would be very proud.”

Family members acknowledge that McElvy had his share of personal demons.

The Plano native was an avid soccer player, who got addicted to drugs in high school. He was in and out of jail. But his family says he loved his daughter very much.

DIGITAL EXTRA: Tina Richardson, McElvy's mother, talks about her son.

Now, the family wants answers from LaSalle Corrections.

“It's not an assembly line,” Wimberly said. “You're dealing with human beings and human life.”

“You need to take responsibility for what you did,” Kyra McElvy said through tears. “Despite what my dad's mistakes were or that he was going through, he needed to be treated correctly and he wasn't.”

Email: investigates@wfaa.com