SAN ANTONIO — Many consider them the "Big 3" of The Alamo: Jim Bowie, William B. Travis and David "Davy" Crockett.

But fighting alongside them during the battle were nearly 200 more men.

For Hispanic Heritage Month, KENS 5 is sharing a Battle of the Alamo story many of us don't learn about, one about brothers who fought on opposing sides.

One was loyal to the Mexican army, while the other joined the Alamo defenders.

They were a family torn apart by war.

Portraits bring Alamo defenders to life

One of the brother's faces can be seen for the first time at The Ralston Family Collections Center, one of the newest additions to The Alamo grounds. Inside, visitors will find more than 500 artifacts—many on display for the first time.

As you walk past heirlooms and centuries-old collector's items on the first floor, you'll find history also decorates the walls. Stories of the Alamo defenders serve as an invitation for curious minds to learn about the men who fought to the death for Texas' independence.

As you walk further, you'll turn the corner to a Battle of the Alamo Diorama. Overlooking the three-dimensional mini replica, visitors are greeted by a few new faces.

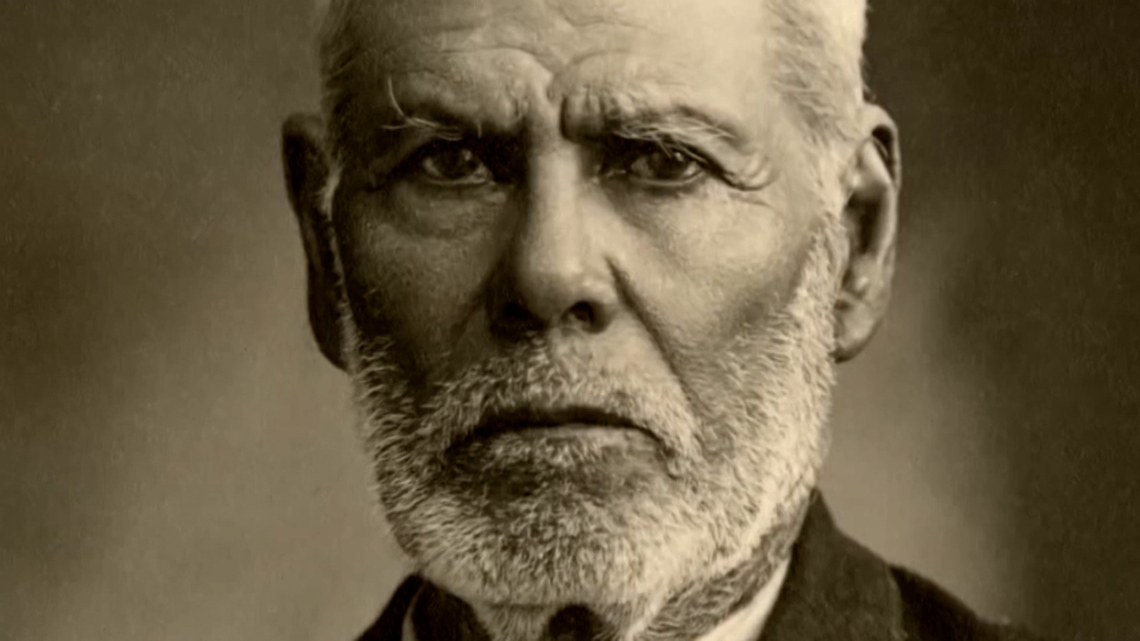

Using 50 photos of descendants as a reference, forensic artist Lois Gibson depicted what certain Alamo defenders who we've never seen may have looked like.

In the center of the new cluster of portraits is 34-year-old Gregorio Esparza.

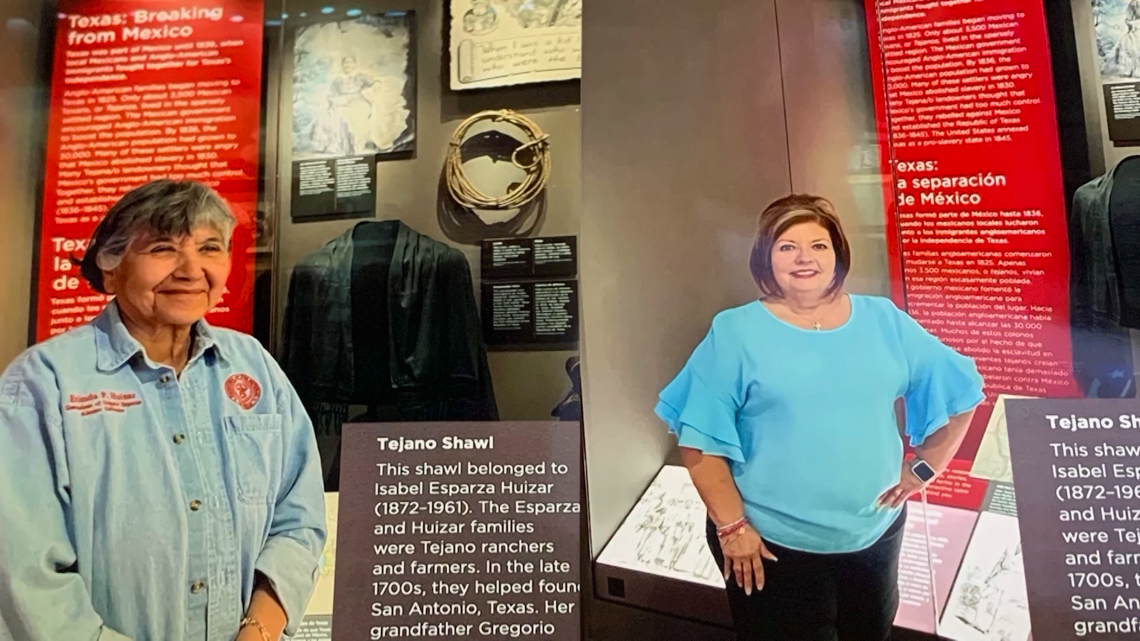

"It has only been recently that the Tejanos have been recognized," said Erlinda Huizar.

"We knew he was important," chimed in Peggy Huizar Guerrero.

Both women view the portrait with admiration and pride, as they are Esparza's great-great-great granddaughters.

"We want everybody to know there are other heroes that need to be spoken about," said Huizar Guerrero.

'This isn't just black and white'

Born on Feb. 25, 1802, in San Antonio de Bexar, Gregorio Esparza lived a modest life as a farmer and father of four. As a Federalist, Gregorio fostered allegiances with his neighbors in rebellion.

His brother, Francisco, was a Centralist who remained loyal to the Mexican government.

They're the only family members experts know of who fought on opposing sides during the Texas Revolution.

"It's really sad, right?" said Ernesto Rodriguez, senior curator, historian and lecturer of The Alamo.

Rodriguez, a dedicated member of the Alamo family for 25 years, is putting together a more complete narrative of the complicated conflict.

"So people can understand that this isn't just black and white," he explained. "A family is torn apart by war, and it's not only torn apart by the violence of the war, but by the whole concept of: What side are you on?"

In December 1835, the Esparza brothers fought each other in the Battle of Bexar and survived.

Three months later, in the early hours of March 6, 1836, Gregorio was manning the cannons at the back of The Alamo.

"He's still on the back wall. The screams of war reach him," said Rodriguez.

Mexican soldiers, under General Antonio López de Santa Anna, attacked the Alamo from different directions.

"Imagine hundreds of guys with lances running in and they're just poking at anything that moves," described Rodriguez. "It's dark, it's nighttime. There's smoke everywhere from the musket fire and the cannon fire."

Gregorio's family hid inside the church sacristy. Their lives were spared by the Mexican army.

"Immediately they see who's in (the sacristy) and they yell out, 'Son inocentes!'," said Rodriguez. "'They are innocent.'"

Gregorio's son, Enrique, was 8 years old at the time. Years later, he described the horrors of the violence to a San Antonio newspaper.

"They asked him, 'Do you remember the battle?'" Rodriguez explained. "He said it is indelibly seared in his mind. Of course, he heard his father's cries for help, his father's cries as he was dying. It's something you never forget."

A legacy lives on

Francisco didn't fight in the Battle of the Alamo himself. He was a reservist at the time. When he learned all the defenders perished, he went to his leader for a favor.

"Francisco went to Santa Anna, asked for his body, and Santa Anna granted it. He was able to take Gregorio's body and give it a Christian burial," said Huizar.

"He's the only Alamo defender to have a Christian burial," Huizar Guerrero added.

When asked their sentiments regarding Francisco, the descendants agreed: He played an important part in their family's history.

"If it had not have been for Francisco, Gregorio would have been burned with the other Texans," said Huizar.

Gregorio was initially buried where Milam Park sits today. When the hospitals were built downtown, he was moved to San Fernando Cemetery.

For Huizar and Huizar Guerrero, their Alamo connection carries great responsibility. It also comes with great respect.

"They're even speaking about The Alamo there in D.C.," said Huizar Guerrero. "That's wonderful!"

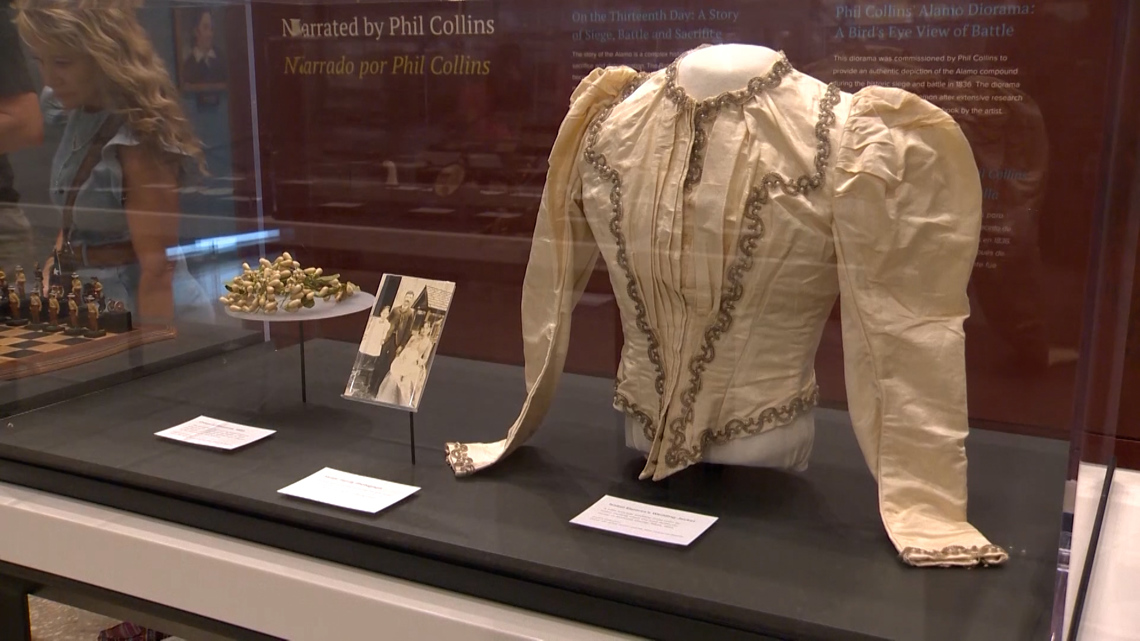

Through Dec. 5, the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Latino has their grandmother's shawl on display.

Next, the family will donate it to The Alamo to be placed alongside their grandmother's wedding dress at the Ralston Family Collections Center.

"We make sure you remember the Esparza Family."