ARLINGTON, Texas -- An accidental discovery in a University of Texas Arlington lab could change the way cancer is treated.

"It's just like roach motel or fly trap," said Liping Tang, Ph. D., UT Arlington bioengineering professor.

Tang calls his discovery a "cancer trap." He says he found that cancer cells are attracted to a certain chemical. He douses a tiny sponge with that chemical, and says cancer cells are drawn to it, then trapped inside.

"Once they go into larger holes, it's like they go into maze," said Tang. "They can't easily get out. That will provide a space where cancer cells can be kept and killed."

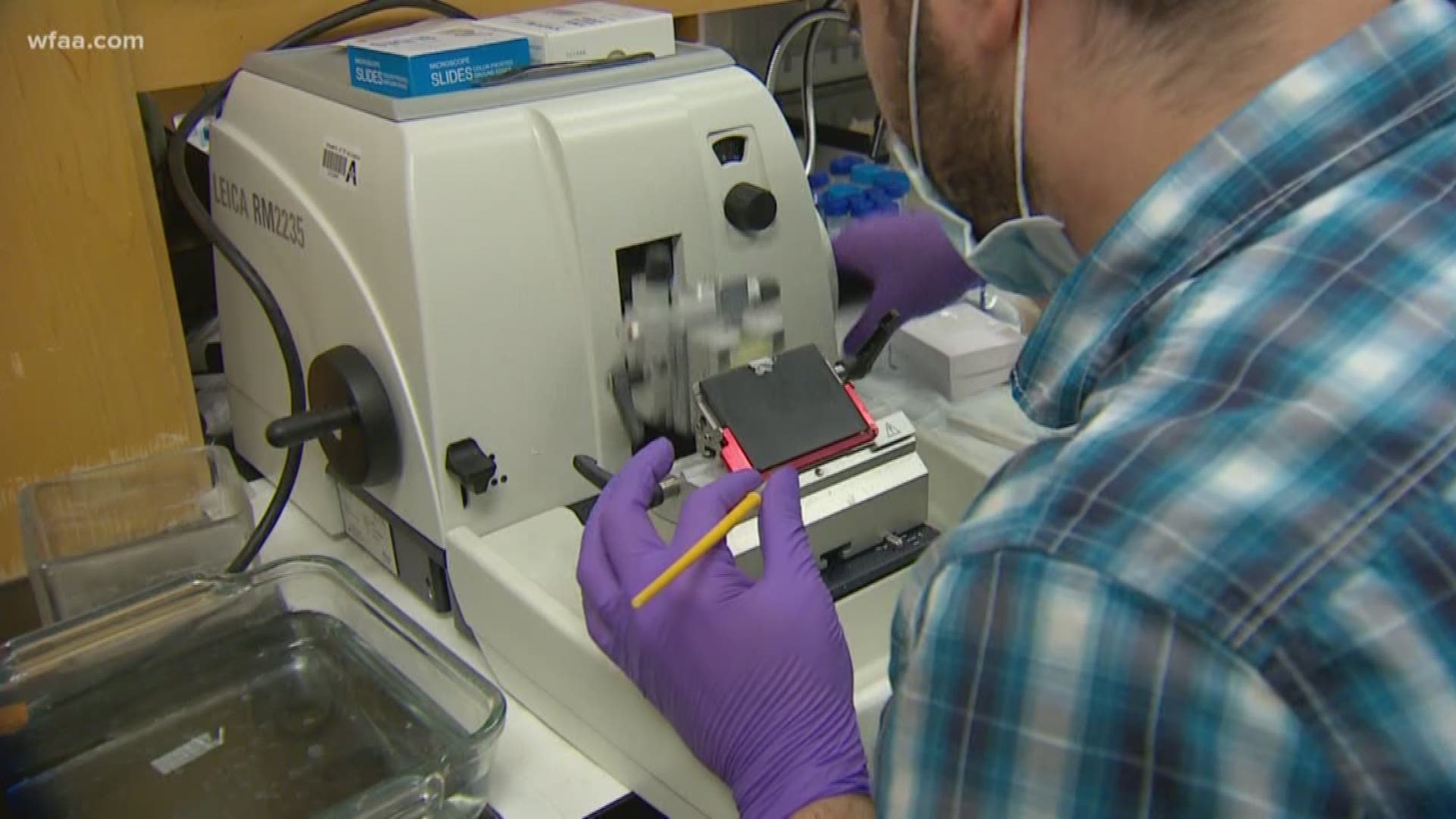

The cancer trap is smaller than a fingernail. It can be implanted into the body, or the chemicals can be mixed into a gel and injected near the site of a tumor.

"This one will be minimally invasive," he said. "You can do it in a doctor's office."

The cancer trap isn't meant to treat a primary tumor but is meant to keep cancer cells from spreading, known as metastasis. It draws those cells to one small area, where they can be more easily treated and far less deadly, said Tang.

"The majority of primary tumors are not lethal," said Tang. "They can be easily taken care of by localized radiation or a surgical procedure, they can easily remove it. The majority of the cancer lethality is caused by cancer metastasis. However, there's no good treatment that is designed for metastatic cancer."

It gets personal for Tang. He has been working on the cancer trap for seven years now, and each time, he thinks of a friend, UNT Professor Zhibing Hu, Ph.D., who died of leukemia.

Tang hopes he can save others from going through a similar loss.

"He's always in my mind," said Tang.

So far, the cancer trap has only been tested in lab rats, but Tang is optimistic that it could be an option for cancer patients within the next decade. Tang has already gotten calls from patients who want to try it, and even a potential investor. It's patented in Europe, and the patent pending in the U.S. He's hoping to start clinical trials in the next three to five years.

"It's very exciting to see," said Tang.