This story originally appeared in The Texas Tribune.

In the first week that Texas adolescents were eligible to be vaccinated for COVID-19, after a year of pandemic-induced isolation from their families, peers and classrooms, more than 100,000 kids ages 12-15 poured into pediatricians’ offices, vaccine hubs and school gyms across Texas to get their shots.

One of them was Austin Ford, a 14-year-old in Houston whose mother is a pediatric nurse, whose father has a disability that makes him vulnerable to COVID, and who lost a family member to the virus last month.

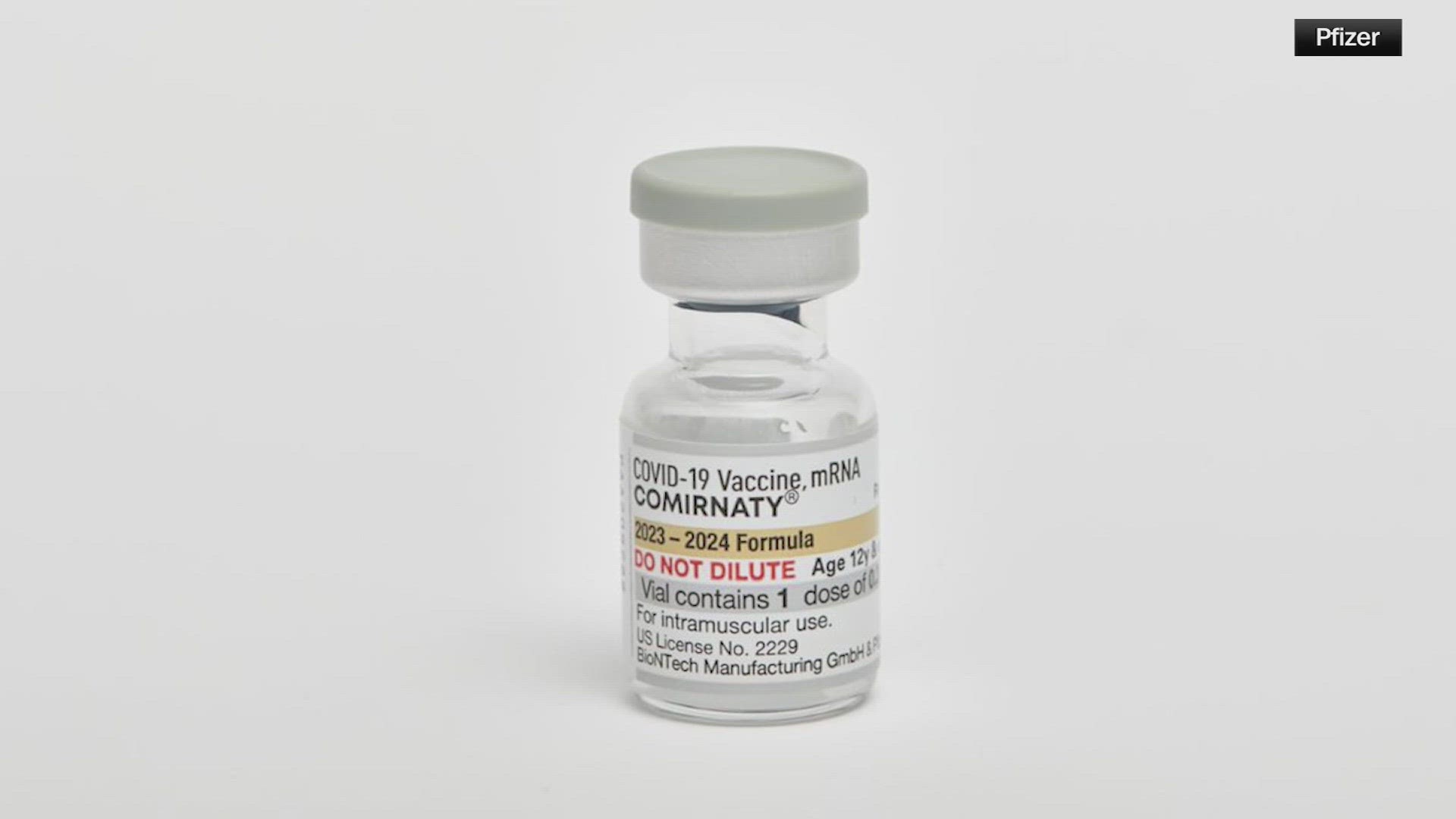

“It was a no-brainer for us,” said his mother, Sherryl Ford, 46, who took Austin to Texas Children’s Hospital for his shot last Friday, less than 24 hours after the Pfizer vaccine was approved for emergency use for his age group. “I have friends who took their kids the night before.”

In the days since the federal approval on May 13, about 6% of Texas children ages 12-15 have gotten a dose of the Pfizer vaccine. It took more than a month to reach that percentage for eligible adults last winter when the vaccination effort began.

It marks a promising start, health officials and others say, to the state’s first attempt to inoculate Texas’ estimated 1.7 million adolescents, who have endured isolation and virtual-learning challenges for more than a year.

“It’s amazing,” said Dr. Seth Kaplan, a Frisco pediatrician and president of the Texas Pediatric Society, which represents about 4,600 pediatricians and other child medicine professionals.

COVID-19 vaccines are not mandatory for Texas students. Last week, Gov. Greg Abbott also banned schools from requiring masks starting in early June, which Kaplan said could be another motivator to get kids vaccinated before in-person school resumes in the fall. Local governments are also banned from enforcing mask ordinances.

For kids like Austin Ford, being fully inoculated by summer means the return of fun with his friends, and all the other social trappings of the early teenage years: trips to the water park, neighborhood pools, group sports and, in Austin’s case, sleepaway camp at an idyllic Hill Country site with one of the state’s longest ziplines.

“It just opened up the world to us, and to him,” his mother said. “It would have been a hard summer [without the vaccine].”

Austin said he would have asked for the vaccine if his parents hadn’t already decided he would get one.

“I think it’s probably because his mom is this crazy nurse that doesn't want anyone to get sick,” Sherryl Ford said, laughing. “And another thing, too: We have worked this hard to keep our family safe all year. We might as well bring it on home.”

Some parents remain hesitant

In Texas, where the issue of vaccinating children for any kind of illness has sparked intense political debate, parents are permitted to opt out of vaccines required to attend public schools, as well as opt in to a statewide immunization registry that tracks childhood vaccinations.

But while Texas health officials have expressed concern about what they describe as a growing anti-vaccine movement, between 97% and 99% of Texas schoolchildren are fully vaccinated, according to the Texas Department of State Health Services.

State health officials don’t expect that high of a number with the COVID vaccine, at least not right away, but say that number signals a high rate of general vaccine acceptance among Texas parents, said Chris Van Deusen, spokesperson for DSHS.

The state is doing research to determine the best messages and outreach for parents, who will be targeted in a public awareness campaign over the summer, Van Deusen said.

Texas pediatricians have also been talking with parents for months about vaccinating their kids, in preparation for its availability to that age group, Kaplan said.

While some Texas parents are adamantly anti-vaccine or don’t believe it’s safe for children, others have different reasons for opposing shots for their kids.

James Davis of Dallas is vaccinated against COVID himself, but says vaccinating his kids, ages 11 and 7, would be a waste of shots because children are already at low risk for catching it and don’t tend to get seriously ill if they do.

Still, Davis figures his children will get vaccinated against COVID at some point when they eventually become eligible, and says he won’t fight it if the family pediatrician recommends it.

"If I had a child with asthma, diabetes or any other high-risk condition, I would vaccinate them as soon as our pediatrician said 'go,’ ” Davis said. "I'm very pro-vax, generally. I think that vaccinating millions of kids is a poor use of emergency vaccines and leaves millions of much higher-risk people at risk on a global scale."

COVID in kids

Rates of transmission, death and severe illness are lowest among young children, but experts caution that they are not immune to its effects. Doctors are still learning about long-term effects the virus can have, including potential issues with depression, said Kaplan, the Frisco pediatrician.

“We’ve had athletes that can’t perform at the same level they performed at before, we’ve had kids that developed ringing in the ears that sticks around for months,” Kaplan said.

In Travis County last week, health officials said the rates of infection and hospitalization among children ages 10-18 were at their highest since the pandemic began, with eight children at the time hospitalized in the county, including a 3-year-old.

Statewide, 52 deaths have been documented in people under 20, including 19 under age 9. And 7% of COVID-19 cases have been among people under 20, Van Deusen said. That’s based on incomplete information; the state doesn’t have the ages for all confirmed COVID-19 cases or deaths, and Van Deusen said an audit over the next few months should improve the data’s accuracy.

In addition, DSHS has confirmed that 151 children in Texas have been diagnosed with a dangerous multisystem inflammatory syndrome they believe is associated with COVID, including one child who died. Two-thirds were hospitalized. More than 75% of the diagnosed children were Black or Hispanic.

A new variant tearing through India was identified in Dallas this week, Kaplan said. Both new cases were in children under 12, according to The Dallas Morning News. The vaccine appears effective against it so far, scientists say, but it’s more contagious and could increase the infection rate.

Dallas real estate agent Richelle Tilghman, 41, can’t wait for her 11-year-old daughter to be vaccinated. She says she doesn’t want to risk long-term symptoms with her children.

Tilghman’s father died suddenly from the virus in the early weeks of the pandemic, Tilghman said, adding that she believes the science showing that the vaccine is safe for children.

“I trust their expertise more than my own. I like to be informed, certainly, but I”m not going to go prowling around on the internet looking for studies I don’t know how to read,” Tilghman said. “I’m not a scientist, I’m not a doctor. I trust the unanimous consensus of the scientists and the medical community.”

Managing the rush

One in three Texans are now fully vaccinated, according to state health numbers. While health officials work to curb dropping demand among adults, they are also trying to manage a crush of parents and kids at the 5,000 providers across the state who are equipped to vaccinate children.

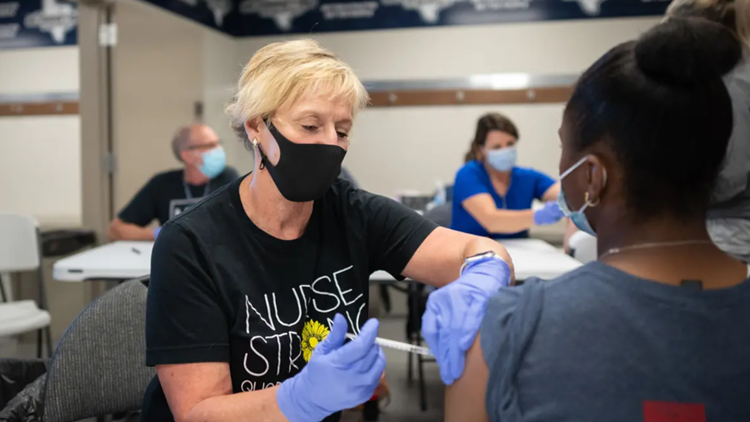

At McKinney ISD Stadium and Community Event Center, north of Dallas, a vaccine clinic last Thursday for district students ages 12-18 drew an average of 300 students per hour, said Shawn Pratt, assistant superintendent of student activities, health and safety for the McKinney Independent School District.

Two recent developments in the storage and distribution of Pfizer’s vaccine have made it easier for smaller pediatric offices like Kaplan’s in Frisco to become vaccine providers, he said.

The state has begun delivering Pfizer doses in quantities numbering in the dozens instead of the nearly 1,000 initially required per order, making it easier for smaller providers to manage their stock, Kaplan said.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration also announced this week that Pfizer can be stored at regular refrigeration temperatures after thawing for up to four weeks. Previously, that threshold was only three days, and the vaccine had to otherwise be stored in specialized super-cold freezers that most small vaccine providers don’t have.

All of that has added to the ability to flood the state with enough supply for any student that wants one before school starts, Kaplan said.

Officials and advocates say lower-income students have more barriers to access to the vaccine, such as lack of health insurance or a regular pediatrician. For this population, schools can play a key role in getting students vaccinated through school nurses or on-campus events where they feel comfortable and spend a lot of time, Kaplan said.

Statewide, more than three dozen school districts from Laredo to McKinney and from East Texas to El Paso have become official providers and have received vaccines, either for students or staff or, in McKinney’s case, for both.

“We want to be part of the solution for our staff and our students, and we want education and our school experience to get back to what it was pre-pandemic,” Pratt said.

Although the vaccines require parental consent, a key part of the enthusiasm appears to be coming from teenagers themselves.

“Most of the kids that I’ve spoken to are really ready to get it because they understand that even though we kind of opened everything up and they are getting back to normal, there’s still a risk for them,” Kaplan said. “If they can get vaccinated, then their participation in activities that they want to be participating in is that much safer for them.”

The Texas Tribune is a nonpartisan, nonprofit media organization that informs Texans — and engages with them – about public policy, politics, government and statewide issues.