In the small sanctuary of Starlight Bethel Missionary Church in South Dallas, emergency room physician Jeff Gusky stands before a handful of listeners.

“It’s the humidity, stupid!” Dr. Gusky says.

He cites studies showing the link between low humidity and flu outbreaks. He says drier air could make it easier for the novel coronavirus to spread person to person.

“It’s accepted that many viruses spread during the winter when the air is dry. COVID-19 is a virus,” Gusky tells his audience.

Data linking the spread of the flu to dry indoor air has been around for years, including in the decade-old study, “Absolute Humidity and the Seasonal Outbreak of Influenza in the Continental United States” by Dr. Jeffrey Shaman.

Shaman and the other researchers found that influenza tends to spread more rapidly in dry air. Other research has reached the same conclusion.

In June, a group in Australia published a study linking dry air to the spread of the coronavirus there. The study compared 749 cases of COVID-19 to relative humidity. It found that with every 1% decrease in humidity, coronavirus cases increased 6%.

Simply put, the drier the air, the more prevalent COVID-19 was. The higher the humidity, the less likely the coronavirus was to spread.

"When the humidity is lower, the air is drier and it makes the aerosols smaller," said epidemiologist Michael Ward of the University of Sydney, one of the study’s authors. "When you sneeze and cough those smaller infectious aerosols can stay suspended in the air for longer. That increases the exposure for other people. When the air is humid and the aerosols are larger and heavier, they fall and hit surfaces quicker."

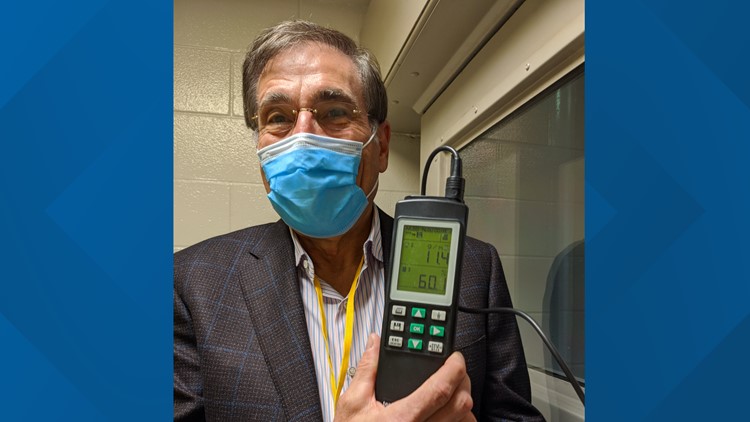

As Dr. Gusky stands before the small group at the church, he holds a device that resembles a large TV remote control. The device is a hygrometer, which measures humidity in the air. For the last several months Gusky has been telling whoever will hear him out that humidity is a key factor in where the coronavirus flourishes.

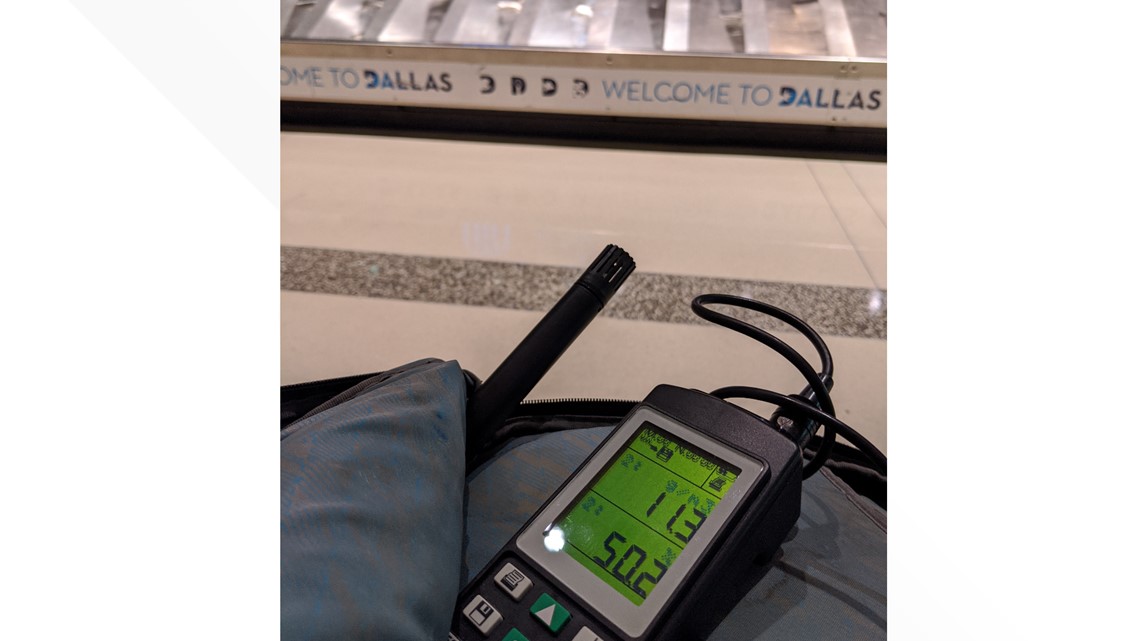

He has been measuring public places like Dallas Love Field, DFW Airport and North Park Mall and found the relative humidity to be above 60% in those places.

(A more accurate measure of humidity is absolute humidity, Gusky says. Safe absolute humidity is air above 10 grams per cubic meter. It correlates with the high relative humidity that seemed to slow the spread in Australia).

The evidence connecting low humidity to the most serious COVID-19 outbreaks is abundant.

In Wuhan, China, absolute humidity is at its lowest annual level in December and January when the outbreak began.

Similarly, in New York City, where the coronavirus has killed the most people in the United States, the indoor air is dry in the winter months.

But the data are not consistent around the globe.

Texas would certainly seem to disprove the relationship between coronavirus safety and high humidity. The muggy days of Texas summer are now producing among the biggest spikes in cases in the country.

The game-changer, Gusky says, is air conditioning.

Texas’ high humidity is tempered by air conditioning in the summer. A/C units work by essentially removing the humidity from indoor air.

“It’s well known that where humidity drops, a spike in flu incidence and mortality occurs.” says Dr. Akiko Iwasaki, an immunobiologist at Yale Medical School.

She says humidity may actually activate defenses in the body that help fight off the coronavirus.

Iwasaki and a group of other researchers released a study last year of mice that indicates dry air inhibits the body’s ability to fight off flu.

“If our findings in mice hold up in humans, our study provides a possible mechanism underlying this seasonal nature of flu disease,” Iwasaki said in a news release about the study.

Some doctors have called on the World Health Organization to publish guidelines on indoor air humidity, saying that higher humidity could slow the spread of viruses that cause respiratory illnesses.

In Dallas, Dr. Gusky says the logical plan of action should be obvious.

“We should be humidifying indoor air. You can buy a humidifier for twenty bucks and put one in every room of your house,” Gusky says.

His plan of action is to couple humidification with a kind of indoor weather report. He says there should be a “Viral Safety Index,” which would measure the humidity.

Public buildings, schools, churches, homes, offices, jails—anywhere large groups gather indoors—should be increasing humidity, he said.

After he shares his message at Starlight Bethel Missionary Church, many in the audience seem ready to buy humidifiers.

But, Gusky says, what scientists and doctors know about COVID-19 changes rapidly. He says humidity isn’t a cure or a guarantee that the coronavirus can’t be spread, but research shows it could help.

Humidity may be a layer of protection rather than a total solution. But, with the evidence, why not give it a try, Gusky says.

More on WFAA:

- Corpus Christi officials report the COVID-19 related death of a six-week-old infant

- COVID-19 game-changer? Houston researchers create air filter that can kill the coronavirus

- Why experts say COVID-19 death rate doesn't give full picture of current situation

- WHO experts to visit China to plan COVID-19 investigation