Enough | Black MENtal Health: Shedding light on asking for help, finding community and resources

This project explores the pain and the conversation surrounding: How Black men are mentally surviving a world that expects them to be strong 100% of the time.

Editor’s note: Some of these stories include details of self-inflicted harm.

The Why Be strong 100% of the time

The date is Dec. 14, 2022, and the death of Stephen ‘Twitch’ Boss has just been confirmed. Boss gained a national following on hit shows like "So You Think You Can Dance" and "The Ellen Show."

You read the comments on social media sites, and they all sing the same tune: “He spread so much joy, he loved his family, he was just posting... 'how could this have been missed?'”

During Black History Month, this project explores just that; the pain that is often hidden and the conversation that is frequently left behind: How Black men are mentally surviving a world that expects them to be strong 100% of the time.

Through the stories of a therapist, a minister, entrepreneurs and a professional dancer, we hope to shed light on the silent battles, the struggle to find resources and what it means to hold space and build a community for Black men.

The next "Black MENtal Health" story will air Wednesday, March 15 in the 6 a.m. hour on Daybreak.

Black Men Healing Jay Barnett

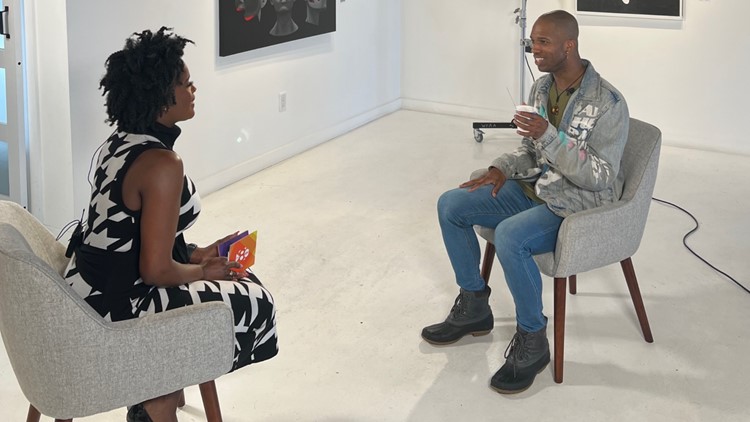

Family therapist and mental health expert Jay Barnett entered the set with a larger-than-life personality. He was fresh off a work trip for his brand Just Heal Bro -- an initiative targeting Black men that takes him across the country, discussing strength in vulnerability and other coping mechanisms for mental wellness.

The first thing you notice about Barnett is his confidence. As a former pro athlete, it is a characteristic you would expect him to have, but is a trait he said took years to develop and fully believe.

He recalled one of the moments he was at his lowest point: “Ten years ago, I attempted suicide the second time and my godmother found me underneath the bed.”

“For most people, it's acknowledging that they need help,” Barnett said. “And that's hard, and particularly for men and men of color, because there's this notion that you have to be strong.”

Barnett admitted there was a lot of re-wiring of his own thinking he had to work through.

“And when you're a Black athlete you don't have space for vulnerability because vulnerability is also a sign of weakness to your opponent,” he shared.

Due to the overlap in his personal life and career, Barnett revealed a big lesson he has learned, “one of the misconceptions that people have about people who struggle with suicide... is they think that they're wanting to end their life, but they're just wanting to end the pain.”

According to the Suicide Prevention Resource Center, the suicide death rate for Black men is four times that of Black women. And even more staggering, the rate at which Black youth are attempting to take their own lives. In 2019, reported suicide attempts by high schoolers (12%) peaked over the national average (9%).

Within the mental health field, Barnett said, “the demand outweighs the solution because there are not enough Black male therapists connecting with young men.”

But he does not want the community to give up. His own journey to healing started by seeking professional help, writing down his feelings, and now he is passing on what he has learned.

“I think if we cannot just create space but hold space for men when they do share and allow them to share in their roles and peers without judgment, that's the key,” said Barnett.

Black Masculinity Cordell Weathersbee II

When you meet Cordell Weathersbee II, you notice how intentional he is, soaking in every word you give him. And soon after finding out he is a choreographer and lover of all artistic things, you realize why attention to detail is so important.

It is the details about himself, though, that took a while to understand.

“I had lots of 'I don't want to be here's,' lots of 'this just feels gross.' I didn't want to be in my own skin,” said Weathersbee.

To understand those sentiments, he reminisced about his childhood, which involved being part of a military family, constantly moving around and never feeling at home in one place. He recalled life growing up in a very structured household.

“Make sure you look a certain way, talk this way. Don't slouch that way,” he recalled being told.

He explained the expectation versus the reality of what his parents wanted from him and who he felt he was deep inside.

“I'm gay. So, it was, ‘I don't want you to be gay.’ Basically. ‘This is not what we look at as right or correct.’”

Weathersbee said he looks back now and acknowledges that this was his parents’ way of protecting him from a society that already had its mind made up of what was “considered acceptable for a Black man.”

Not only did he feel the pressure at home, but he also dealt with others who misunderstood him as a child.

“I'm listening to these people tell me what I am," he said, "and then I'm making that my reality.”

It wasn’t until college that he finally felt his voice was heard.

“I had a therapist that was very helpful, and I was able to talk," he said.

Getting into adulthood, Weathersbee was able to find his stride. He was booking gigs, challenging himself in the dance world, and he decided to pack up and move to Dallas to further expand his career.

“My goal was: I just want to perform. I want to do more,” he said.

But the move came with unexpected hardships.

“I lost my car, I lost everything. And that was like a moment for me to be like, okay, what do I do?”

In his time of need, Weathersbee turned to community and reading, which helped re-affirm who he knew himself to be before being faced with so many challenges.

Now, he is a mental health advocate but admits the journey to healing is never truly finished.

“There's always different areas that we're always consistently working on. Nobody's ever done. That's why we have life,” said Weathersbee.

Learning to Pivot William Toliver

Hopefully, the name “William Toliver” rings a bell. WFAA spoke with him during the height of the pandemic in 2020. The former science teacher blew up on social media by displaying his artwork through TikTok. So, if anyone can relate to a pandemic pivot, it is the teacher turned fulltime entrepreneur.

Fast-forward three years, and Toliver said he has felt all the joys, and especially, the pain of fully focusing on art.

“I went from not having to worry about like my necessities in life to deciding whether I should put money into groceries,” he said.

Toliver said everything he worked to build over the past few years slowly started to fade away, but no one could tell because all they saw was the attention -- they assumed -- he was getting from his work.

“Life was building up on top of me and it felt like slowly drowning, essentially, you're there by yourself,” he said.

For the 33-year-old, it would take another pivot: asking for help. This is a task Toliver said took more courage than he could have ever imagined because of the stigma.

“When you're a young man growing up, you're told you have these responsibilities; you should be able to take care of yourself,” he said.

The self-described rollercoaster he has been on inspired his latest body of work, “After Dark.” The whole collection is Toliver’s take on redefining mental health boundaries.

“I went into it like, this is me and I hope that you like it. And if you don't, that's okay, because I did this for me.”

The black-and-white artwork is pulled together with pops of red. It is Toliver’s way of creating space for people who may feel they are still figuring out a path.

His goal right now: “Finding consistency and finding people that will continually push this idea, this movement of vulnerability and mental health in our community.”

The Black Church and Mental Health Joel Tudman

Joel Tudman and Jay Barnett are close friends. Imagine the regular banter of catching up, laced with inside jokes and humor that leaves your sides aching from laughing so hard. The energy is unmatched, and so is the competitive nature between the two.

This brotherhood was not always so simple.

Tudman is a minister and knows all too well about the “traditional remedies” for healing in a Black church.

“Calling certain mental disorders demonic, saying that you don't need therapy, you just need God? I think those are a direct reflection of how men and women have decided not to go and to just talk to pastors,” said Tudman.

He was a stand-out athlete growing up and even committed to playing football on the collegiate level until an incident with a teacher spiraled out of control, landing him in jail. Tudman said the only one who did not shame or abandon him after the fight with his teacher was his grandmother.

“For about 10 or 15 years, I didn't fool with my family,” Tudman admitted. “So, I in essence, I kind of turned into a monster that became successful financially, but emotionally, never learned how to express myself psychologically.”

By this point in his adulthood, Tudman had already been in the pulpit and even had a minor degree in counseling. But it took him a while to admit he still needed help.

“It becomes difficult for people to even think that you've got a problem because they're doing so well externally, and you've learned how to hide it internally,” he said.

A man now in his mid-40s, Tudman said it was not just counseling that brought him through those internal hurdles but forming true, adult friendships and having others to hold him accountable – which is why friendship with Barnett is so significant.

“Having someone in your life that can actually contribute positivity, and stretch your thinking, expose what’s wrong to you in that private space,” said Tudman.

He added that companionship is also not being afraid of the culture of correction. “All of that helps you create the space where community isn’t just about, ‘Hey, I’ve got your back.’”

Tudman said he wants to set the tone for future generations. First, by being as authentic as possible in the pulpit and second, by encouraging people to find community.

“Don't be afraid to talk. Find somebody that you can trust. And it's going to be a risk. It's going to be scary,” Tudman said. “You're not going to want to share. But sharing now is so much better than holding it and letting it compound later.”

Overcoming past trauma Patrick Jefferson

As a dancer with Ballet North Texas, Patrick Jefferson knows the act of performing all too well. When he is on the stage, dancing serves as an outlet. But for a long time, Jefferson had to work through what was happening when the lights went out and the curtain closed.

The world may never know how much pain Stephen ‘Twitch’ Boss went through, but it is a feeling Jefferson said he relates too.

“It is always the ones who put on the biggest show for everybody,” Jefferson said. “They could seem as happy as they're ever going to be in life. But ultimately, there could be something behind that wall.”

Early in his childhood, Jefferson was unintentionally encouraged to put up his own walls. He wanted to get help for his father – who was dealing with addiction – but that was met with pushback from other family members.

“It was basically, you're airing our family business. That doesn't need to be aired out,” he recalled.

For years, Jefferson said he carried that mindset, using it to avoid getting help of his own.

“I didn't know that the smaller things could basically become a snowball on a hill and turn into the bigger aspects of suicide,” he said.

Today, Jefferson understands there’s a better way of thinking after coming to the realization that he could not solve his deep-rooted issues on his own. He eventually took it upon himself to get checked into a psychiatric hospital. He also started to lean on his family and friends for support.

“Find a community and people who you can love and trust,” he said.

Jefferson said he is still working through his mental health journey but the best thing he can do is to allow himself to be open.

“Sit with yourself and realize when you have too much on your plate, communication is the best thing you can do.”

Community: Creating and Holding Space Jay Barnett and Joel Tudman

You have probably heard the term no new friends but the older you get, the harder it may be to accomplish a task that seemed so simple as a child.

Looking at Joel Tudman and Jay Barnett, you would not be able to tell the two grew close in their 30s. Reaching out took persistence and some persuasion.

“I would text him, he wouldn’t text me back and he would leave me on read for days,” said Barnett.

For Tudman, replying to a text message seemed more like a daunting task than just accepting an invitation, “I could tell right out that he wanted friendship and I didn't know if I was prepared to give that.”

Tudman reflects on his past when a long-time friendship ended and how deeply it hurt him. It was not until years later when he realized the only way to heal was to let someone else new in.

“It is so important for brothers to have community because the worst place a man can be left is left alone with his thoughts and feel that no one cares,” Tudman shared.

“Community provides hope,” he added.

Community has been one of the single greatest keys for both men. They both struggled in the past (you can read about this in their individual stories) and had similar revelations: to not re-live the past, something must change in the present.

“Community is being able to have a safe space where we have a correction culture, where we have culture to fix what's been broken,” said Tudman.

When approaching new friendship both men agree it is all about the perspective you take into the relationship. They suggest instead of asking, “What can this person do for me?” There should be a shift in mindset to “How can I fully show up to help this person?”

"I think it's important for brothers to know that it is a risk,” Bennett added. “Friendship's a risk like relationship is you may take a risk and it may not work out. It is okay.”

Help is available Mental health resources

If you or someone you know is struggling with thoughts of suicide or self-harm, there’s help available. Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255; the Trans Lifeline at 877-565-8860; or the Trevor Project at 866-488-7386. You can also text “START” to Crisis Text Line at 741-741. If you prefer to not use the phone, consider visiting www.crisischat.org.

Dallas County Commissioner for District 3, John Wiley Price, said Dallas Independent School District is leading the nation in response to mental health resources for teens. Dallas ISD has dispatched more than 270 counselors and clinicians so they have direct access to care -- which is generally free of charge, says Wiley Price: Dallas ISD Students, Dallas ISD Parents & Students and Dallas ISD Mental Health Services.

WFAA also spoke with the owner of the nonprofit organization Litehouse Wellness, Sherri Doucette, on the importance of creating a space for Black men needing mental health guidance.

"I need my Black brothers, my Black sons, Black community leaders, advocates to, those men to thrive to move beyond survival," Doucette said. "Because at this rate, they won't make it."

Doucette said Litehouse is kicking off a free event on Sunday, Feb. 26 called "The Dock", where virtual and in-person mental health conversations can take place. The in-person event invites those who participate to connect with each other as four license Black male therapist facilitate.

It will take place at APAA located at 2800 Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard in Dallas at 5 p.m. Click here for more.

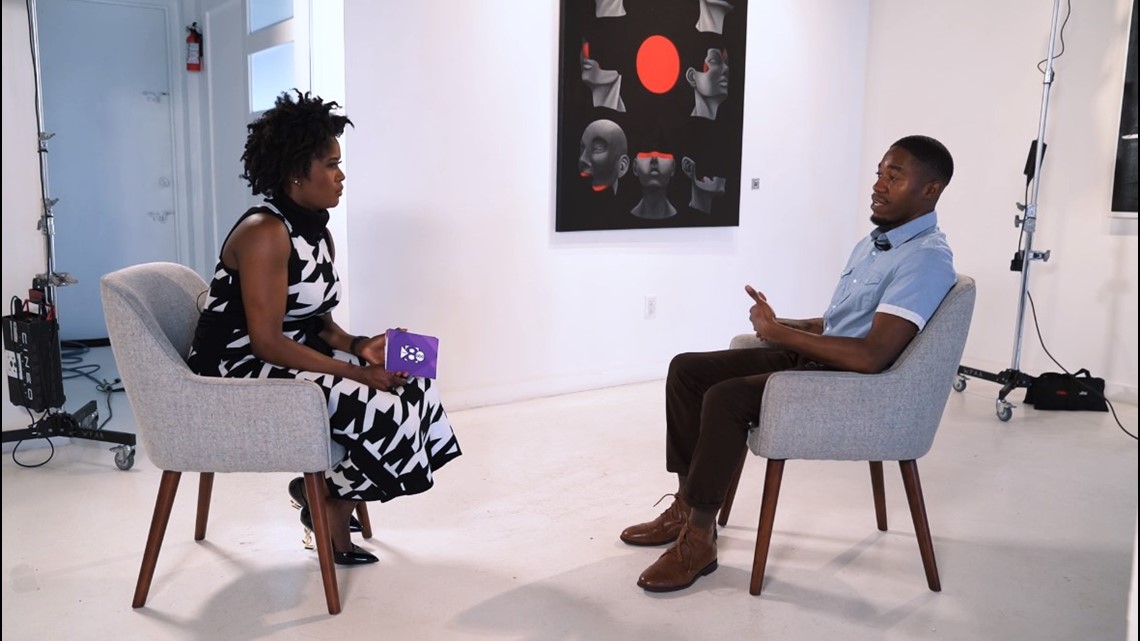

Enough | Black MENtal Health: Behind the scenes