DALLAS — The first time George M. Johnson heard that someone was calling for their book to be taken out of school libraries was last fall.

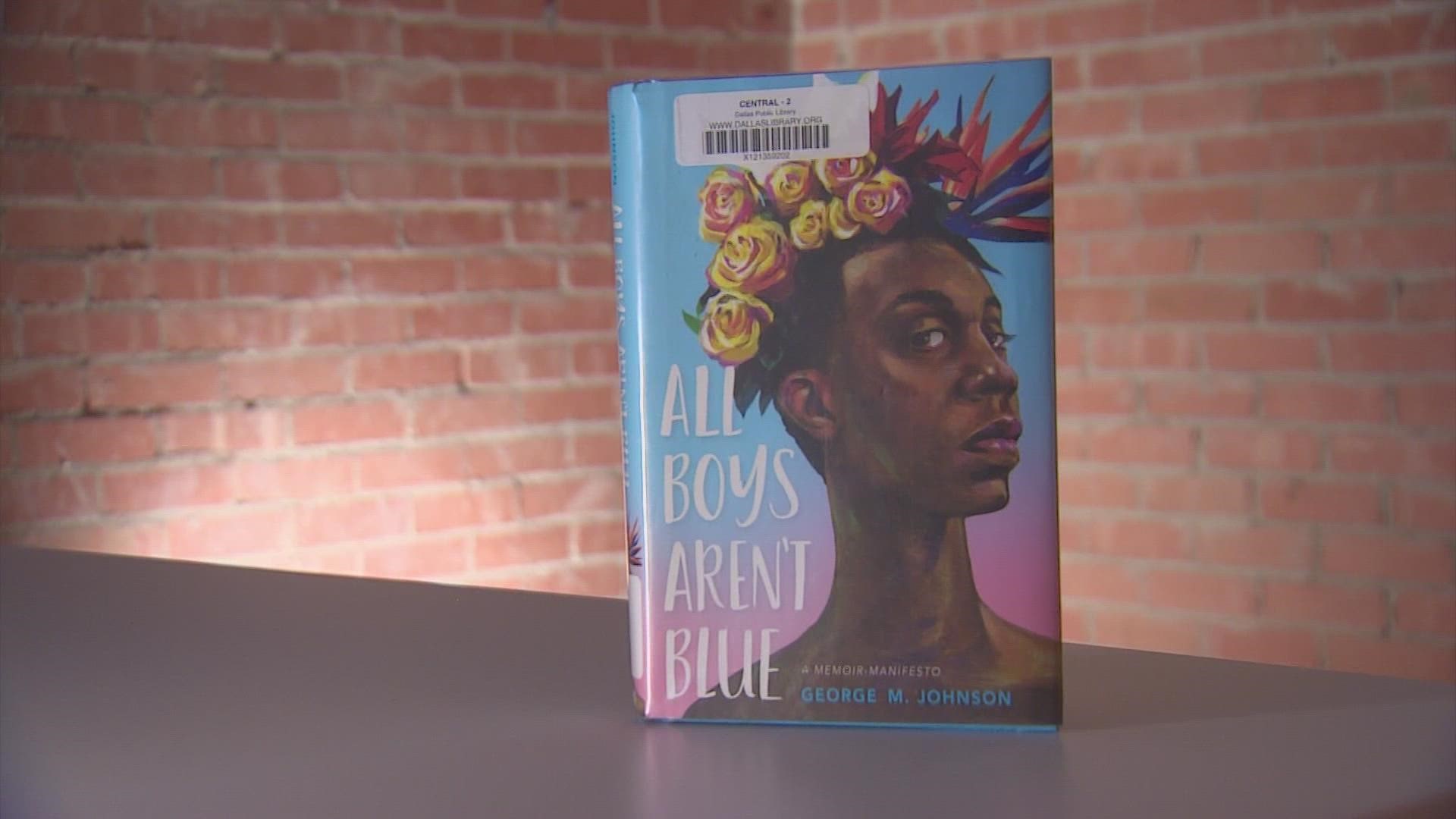

A conservative school board candidate in Kansas City created a social media post stating that Johnson's memoir-manifesto, "All Boys Aren't Blue," should not be allowed in schools.

Johnson said they responded to the post, and the candidate removed it shortly after.

"I thought 'Okay, that will be over,' but then it became clear that they had a targeted strategy that we just didn't know about," Johnson said.

"They" being a wave of conservative groups that have aligned themselves with school districts across the country, and in North Texas, to back school board candidates and push for certain ideals to be adopted into district policies.

Some of those policies have circulated around library books.

"Like eight weeks later, eight other states had started pulling it," Johnson said. "They were all pulling the exact same books. It was very clear they had a targeted list of books they were going to target across the country, using the exact same passages….using the exact same language to try and get our books removed.”

Last fall, Texas state Rep. Matt Krause created a list of 850 books and pushed for school districts to review them for removal from libraries. A majority of the books center on racism, gender identity and LGBTQIA+ issues.

"All Boys Aren't Blue" isn't on the list, but it's been removed from at least two Texas school districts, including Frisco ISD.

According to the district's website, the book was on high school campuses before it was removed in September. It is being reconsidered by a committee, but is currently not on any campuses.

“I wrote this book for the teen reader that I once was who had no books where there were characters that looked like me...that had no characters where I recognized myself in the story," Johnson said. “Despite how we identify, I think many of us are on some type of identity journey, especially through our teen years.”

Johnson's memoir is a collection of stories about their upbringing, their first experience with bullying, their journey navigating the multiple layers of their identity and what that's meant for their safety, health and relationships.

"It’s also the story of a Black family that loved and affirmed a child that was queer," Johnson said.

They discuss their experience with joining a fraternity, finding their voice and what they've come to believe about gender and sexuality.

At they very start of the book, Johnson states there will be topics that many believe are too "heavy" for teens but goes on to say the stories are their lived experiences and that the book is for teens to help navigate their own.

The book has drawn criticism and outrage particularly for one chapter in which Johnson details an incident of statutory rape as a young teen who was trying to navigate their sexuality and identity.

"You have to read the entire book," Johnson said. "It would be like reading one chapter of The Bible and trying to assess everything else. There’s no way you can read three different passages, because there are three passages they’re taking complaint with, out of a 320-page book and think that the whole book needs to be thrown out."

Johnson, a journalist and New York Times best-selling author, said that standard isn't applied to other outlets like movies, music or television.

Other authors have also spoken out about their books being removed from shelves.

New York Times best-selling author Jodi Picoult posted to Twitter after her book "19 Minutes" was banned from a Texas school district.

Picoult's books usually tell stories from multiple perspectives. "19 Minutes" is about a school shooting committed by a student who was a victim of bullying and lays out narratives and surrounding storylines from the people affected by the shooting. Critics called the book "pornographic," labeling a part of the story as "teen sex."

The part of the story in question detailed one teen being sexually assaulted by her boyfriend.

"You look at the rates of sexual abuse on college campuses and everybody's wondering why it's so high. It's because you're sending 17 and 18-year-olds into the world with nothing," Johnson said. "You remove the books that would've taught them what consent was, taught them what agency was and taught them what 'no' means."

Johnson said removing books like theirs is a "non-starter" in current society and culture.

“Whether it’s drugs…whether it’s identity crisis…whether it’s sex...gender…the teens are already dealing with these things," Johnson said. "You are making a dangerous assumption when you say that our books are what’s introducing them to topics they may be trying to navigate without any resources."

Johnson said the idea of what's appropriate, especially for teenagers in high school, is a "construct" that pales in comparison to what teens are actually being exposed to from their peers, social media and the Internet.

“Even if your teen had never read my book, if you ask them about five different subjects that are in my book, your teen is going to have an answer for it," Johnson said. “Books don’t introduce these topics. The internet exists now, social media exists now, so it’s just a very interesting thought process that you think books are where teens are getting the bulk of their information on sexuality, gender, identity like they just can’t cut on the television and see it every day.”

Johnson said their book is a resource they could have used as a teen as they were making decisions about their body. They are open about living with HIV and advocate for awareness, and they believe more education could have made a difference in their life.

“What would have happened if, at that age I was taught that, 'Hey, even though HIV is a thing that effects everyone, it specifically effects your community George…it specifically effects people who look like you?' I may have never been diagnosed," Johnson said.

Johnson said banning books won't erase racism, people in the LGBTQ+ community, sex or any of the other issues in their memoir.

"Gay people are not going anywhere," Johnson said.

Many conservative parents and school officials have expressed that people should be able to purchase or obtain books that have been banned if they want to but argue they shouldn't be available in school libraries.

Johnson argues that parents have the right to make decisions for their own children, but that banning books from entire districts takes that a step too far.

“If you want to opt your child out the book, go ahead and opt your child out the book," Johnson said. "You don’t have the right to opt every other child out the book. Your parental right cant usurp everybody else’s."