HOUSTON — Editor’s Note: To reconstruct this story, reporters Grace White and Matt Keyser spent months reviewing the case file, provided by the Harris County District Attorney’s Office. That was complete with original police reports, investigators’ notes and interrogation tapes, crime scene photos, and Jaime “Jim” Melgar’s autopsy report. White and Keyser spoke with prosecutor Colleen Barnett, who provided great detail about the state’s case against Sandra, and family members of Jim and Sandra, who provided valuable insight into their life and marriage.

I.

There are nights when Sandra Melgar is lying in bed in her six-by-ten-foot prison cell, the loud hum of fans not far away, when she thinks back to where her life went wrong. Sandra never imagined she would be widowed and a suspect in her husband’s murder, never believed a year and a half after his death that a grand jury would quietly indict her, and almost five years after his death a jury would convict her on circumstantial evidence—no clear motive or physical evidence linking her to the crime—and sentence her to 27 years in prison. For Sandra, now 59, every day since her husband’s death has been a nightmare.

For the past 10 months, Sandra has called the William P. Hobby Unit home. The all-women’s prison sits among the cattle and barbed-wire fences off rural Highway 6 in Marlin, Texas, a sleepy town tucked in the farmland about a half hour southwest of Waco. The prison houses more than 1,300 prisoners—some of whom are serving life sentences for capital murder, others serving a couple of years for robberies or aggravated assault. Her days are much more structured now: she eats breakfast each morning around 4, stops by the medical center to take her prescriptions, and otherwise spends much of her days in her cell reading or doing puzzles or learning Italian, because it’s too painful walking long distances throughout the prison.

“Sometimes I think I’m going to go home. I still think, ‘I want to tell him this,’ and I forget he’s gone,” Sandra said in a recent interview. She wore a white jumpsuit and used a wooden cane that was far too tall. Her blue eyes were red and puffy as tears streamed down her pale cheeks. “I don’t feel like he’s really gone; I just feel like he’s temporarily gone or just on a trip out of town. I try not to think of…” She paused for a moment. “I know I will see him again.”

Sandra maintains contact with her friends and family, many of whom still believe in her innocence. She speaks regularly on the phone with her daughter and only child, Elizabeth “Lizz” Melgar Rose, though the loud prison and Sandra’s soft voice don’t always make for the best conversations. Sandra writes letters to friends, who give her updates on her Pomeranian, Lola, who was in the house the night of the murder. Most weekends, she spends two hours visiting with a rotation of friends and family thanks to one of her best friends who coordinates the weekly visits.

Lizz is her mother’s biggest advocate, the one who’s taken it upon herself to serve as her spokesperson and discuss what she describes as the injustice that took both her mother and father.

“I’ve never seen my mom so broken and devastated, and she never recovered after that. She’s never going to be the same person. She will always have this hole in her life. I just can’t put into words how this has affected her because it’s been such a tremendous loss,” Lizz said recently.

Sandra struggles to remember what happened on Dec. 23, 2012, the night her husband died, an all-too-convenient fact that led investigators to suspect she killed him. But she’s adamant: She didn’t do it.

II.

Barking dogs startled Sandra awake. Her vision blurred as she struggled to make sense of where she was. Her muscles ached and head throbbed as she lay on the floor of her bedroom closet, her hands and feet bound behind her back, her underwear soiled. Sandra, who stands 5-feet 4-inches tall, tried to stretch out her legs and rollover to peek through a gap under her closet door, but her bindings and two hip replacements hampered her movement. Not that she could leave even if she were able; a chair was propped under the door handle from the outside.

Feet away in the bedroom closet, her husband of 32 years, Jim Melgar, lay lifeless with 31 stab wounds to his hands and chest. Blood stained the white walls. Crimson spatter scattered throughout Jim’s clothes, the white carpet and on his black briefcase. Blood was smeared on the handle of his safe next to his body. His feet were bound by a gray telephone cord. A medical examiner would later determine all of Jim’s wounds were defensive: various stabbings to his chest and hands and none on his back, showing he attempted to fight off his attacker rather than run, including an especially brutal strike to an artery near his right thumb, which had been nearly sliced off and likely caused much of the blood spatter in the closet and bedroom.

Dresser drawers in the bedroom appeared ransacked with clothes, books, and pill bottles strewn across the floor. Sandra’s black purse and red wallet appeared looted on top of the bed with various cards tossed on top of the white comforter that was also stained with speckles of blood. A small white medical stool sat at the foot of the bed partially covered in blood—leaving a stain that looked as if the blade of a knife had at one time been placed there. Next to the bench, the back of a wooden chair was stained with scarlet drippings.

In the partially filled Jacuzzi bathtub, where Sandra and Jim spent the previous evening, sat a white blouse, a green towel and a silver chef knife with a 6-inch blade and blood droplets that crept into the tiniest crevices. Police would later determine that was the weapon that killed Jim.

Hours earlier, Sandra and Jim spent the evening celebrating their 32nd wedding anniversary. The two ate dinner at their favorite Mexican-food restaurant and planned to continue their celebration in their Jacuzzi with candles, cocktails, strawberries and whipped cream.

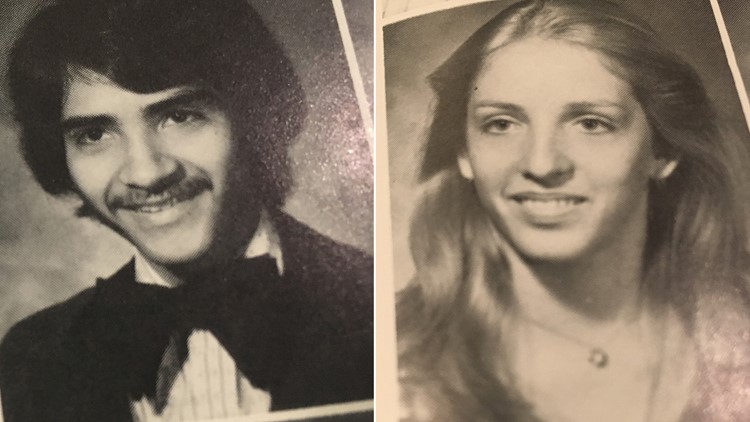

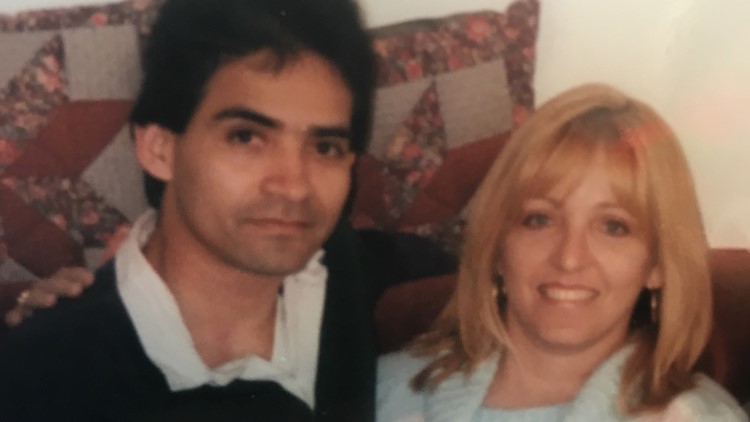

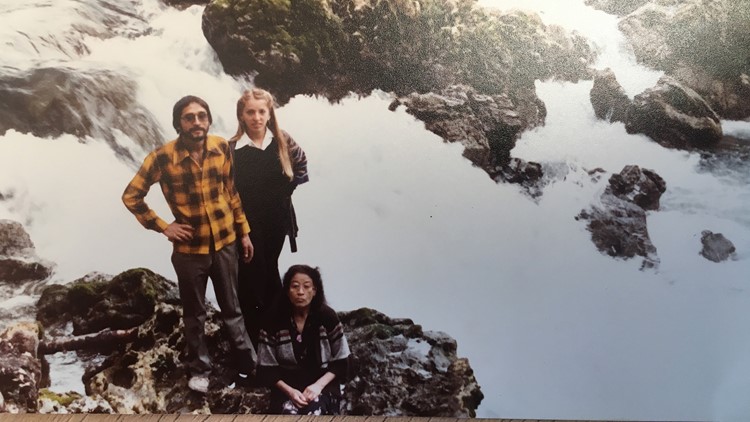

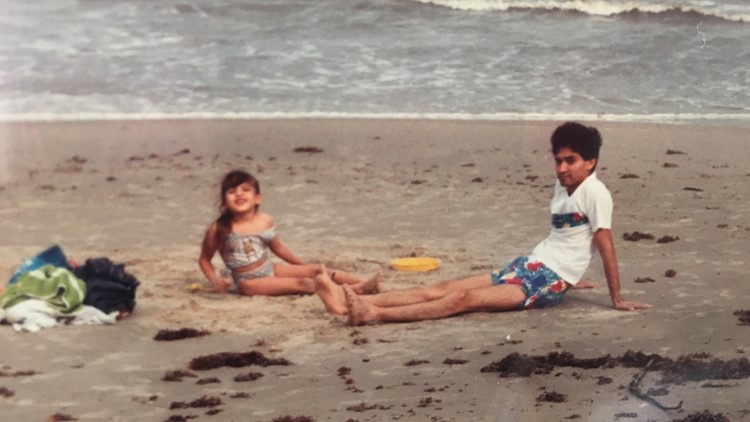

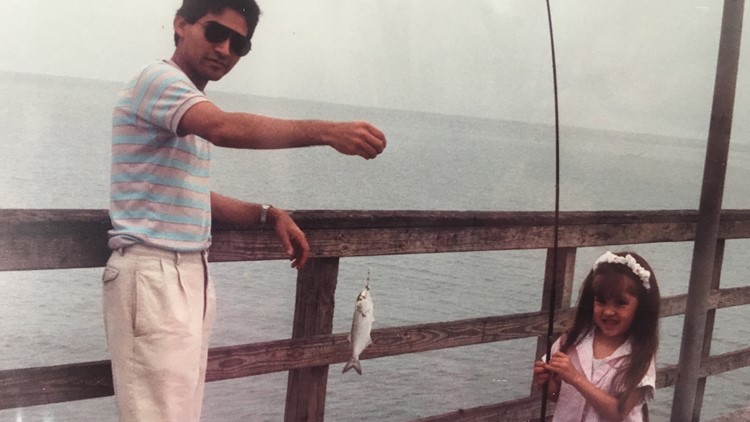

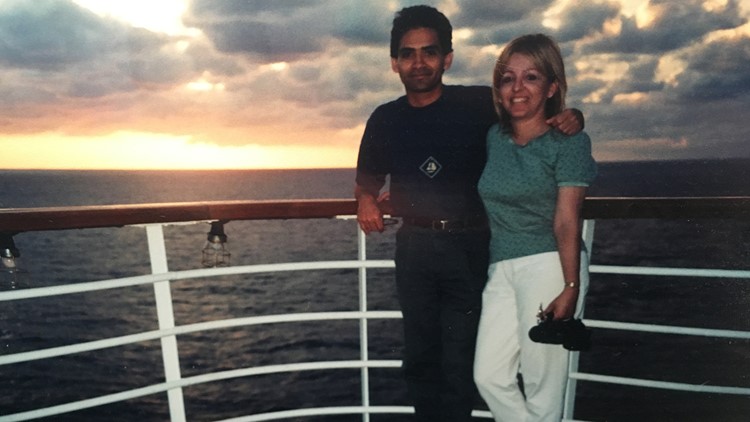

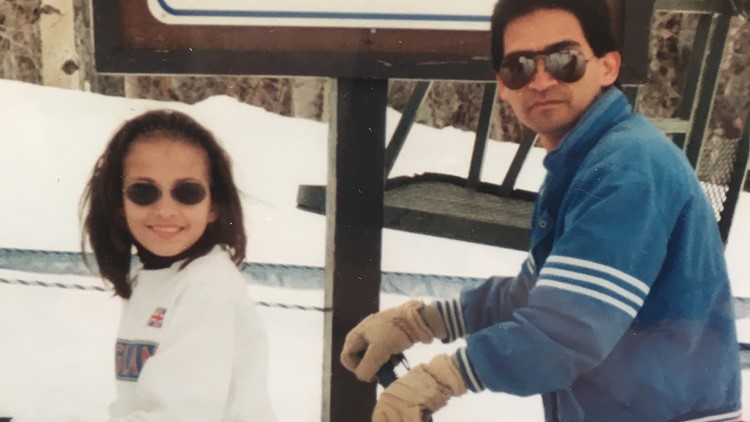

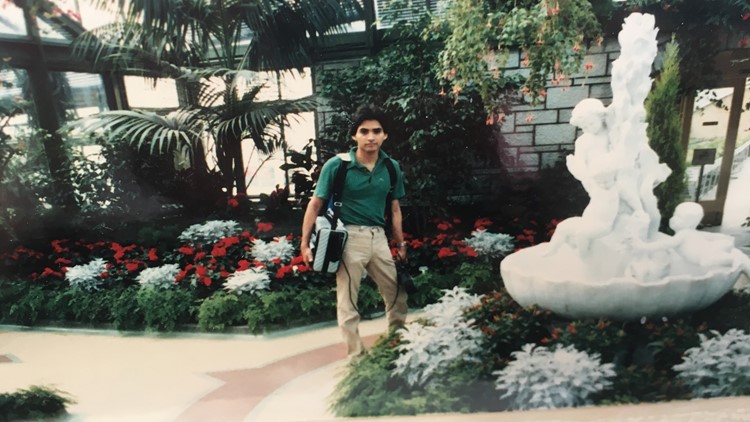

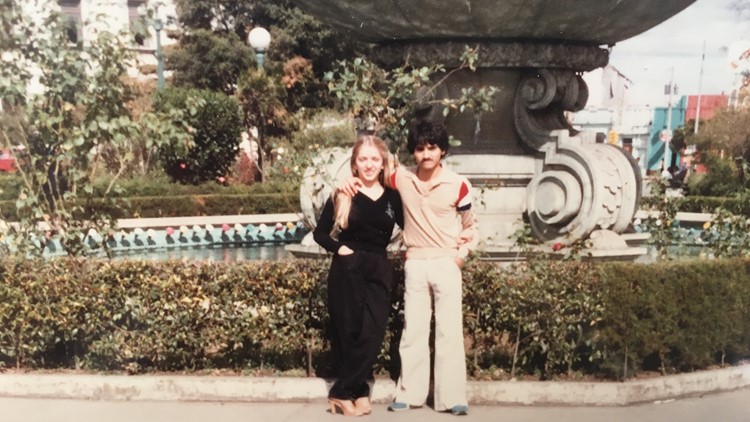

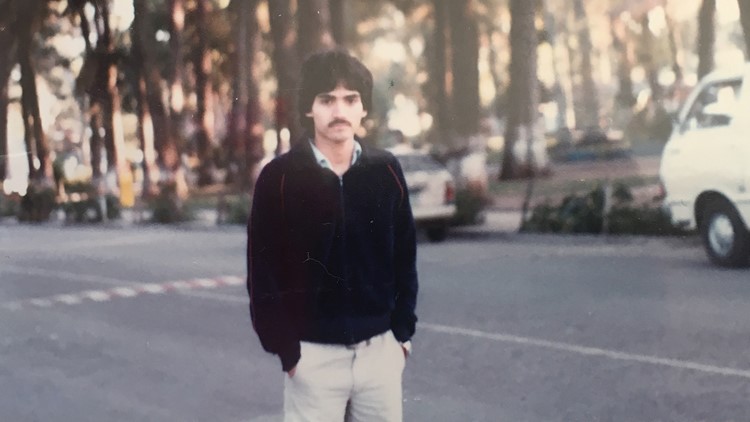

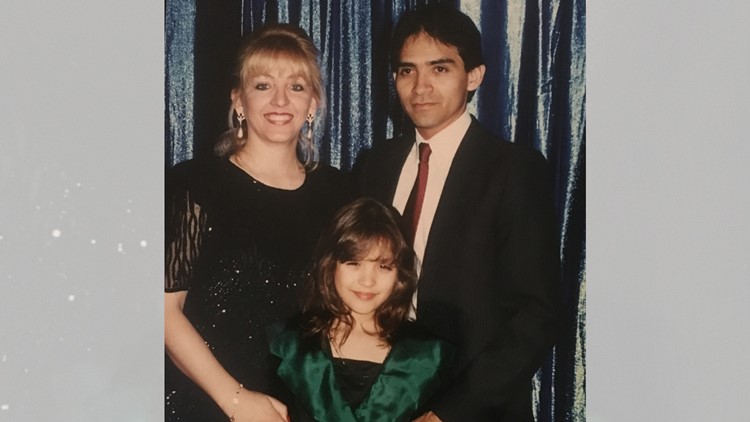

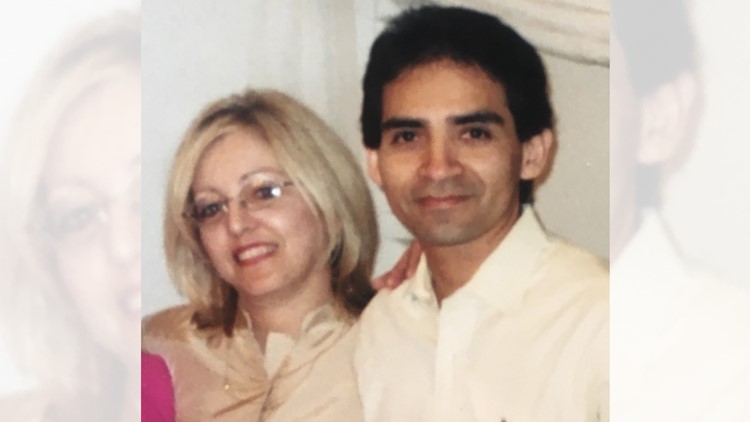

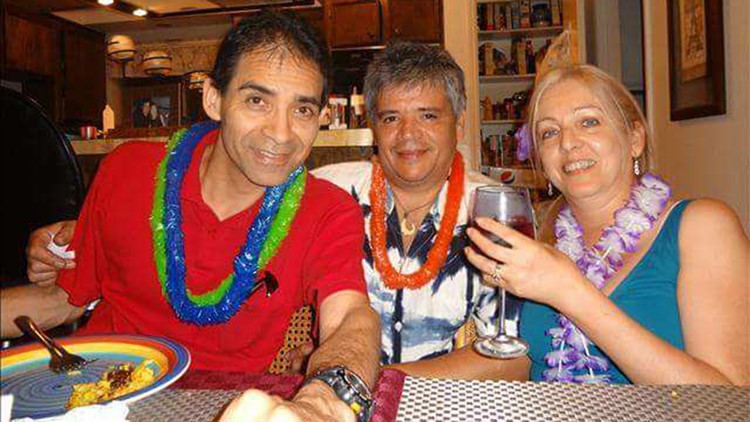

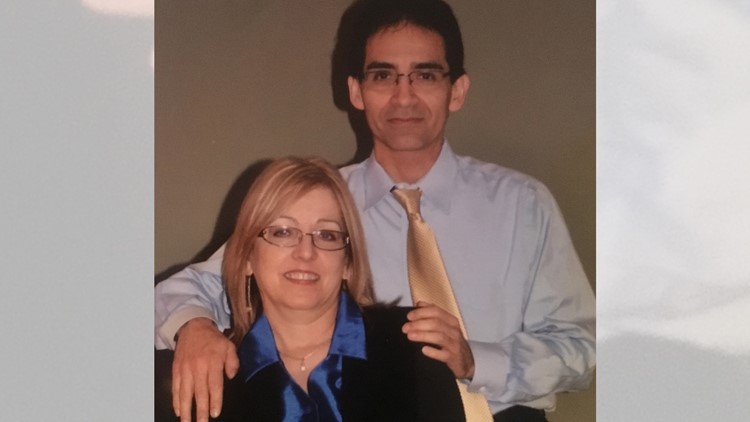

Even after more than three decades together, Jim and Sandra were still very much in love, she would later tell police. They first met their senior year at Lamar High School. Jim, with his shaggy black hair and awkward teenage mustache, immediately took a liking to the 17-year-old girl with blue eyes and blond hair who sat in front of him in class. Jim tried to get Sandra’s attention by pulling her hair. Sandra was the new girl at school, having moved to Houston from Laredo; Jim, meanwhile, had lived in Houston nearly all his life after immigrating from Guatemala at 3 years old with his mother and two brothers.

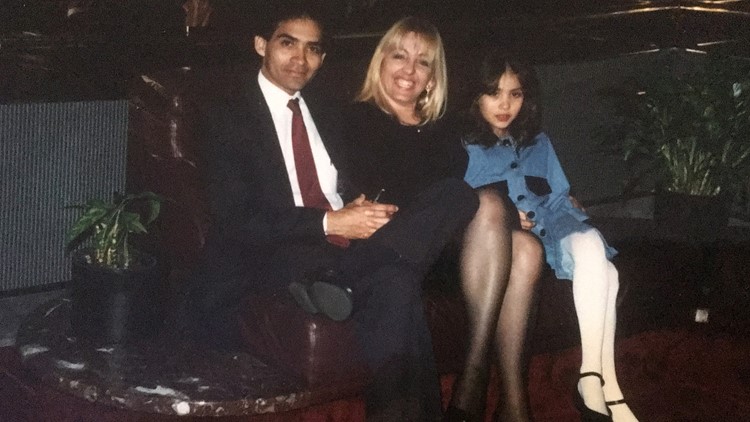

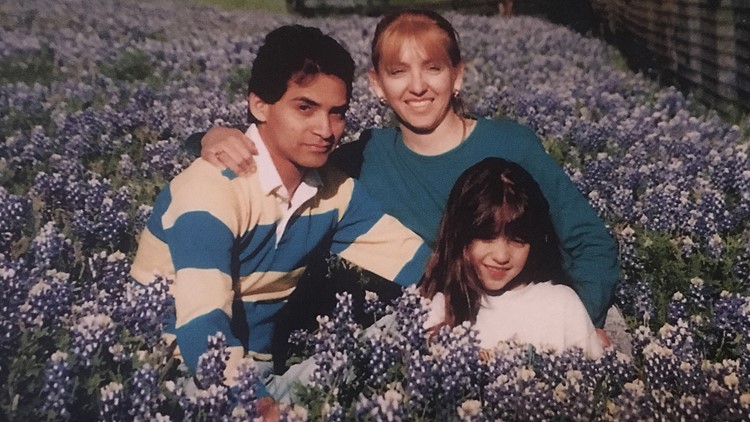

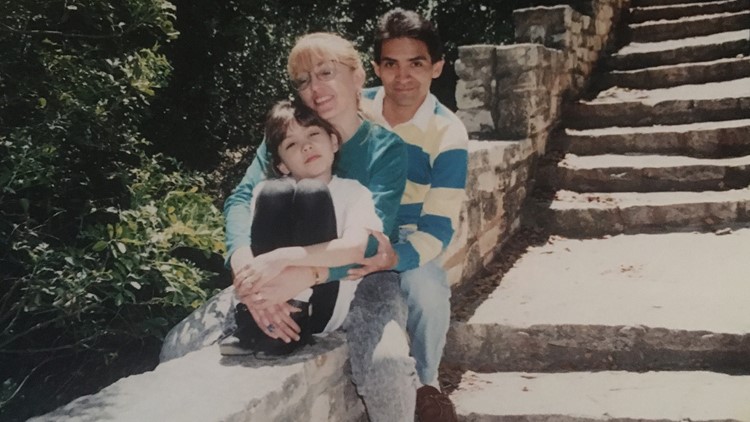

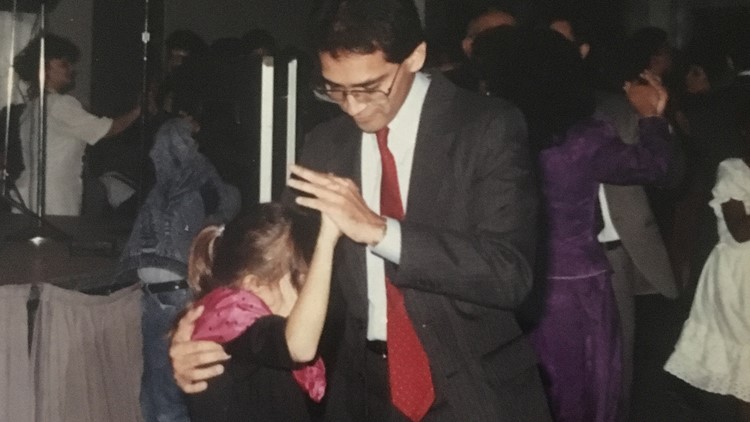

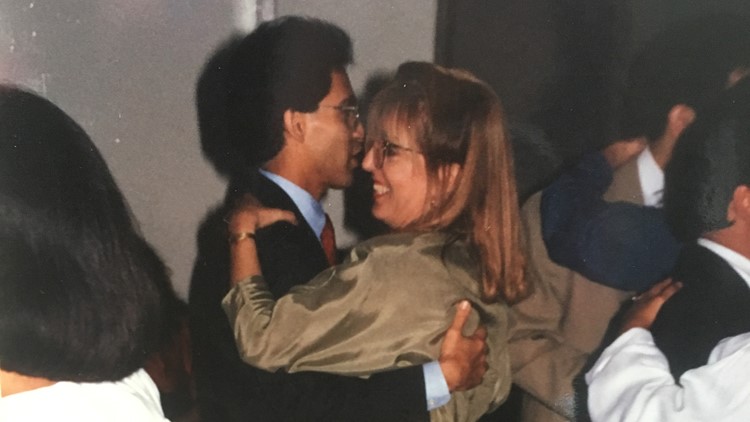

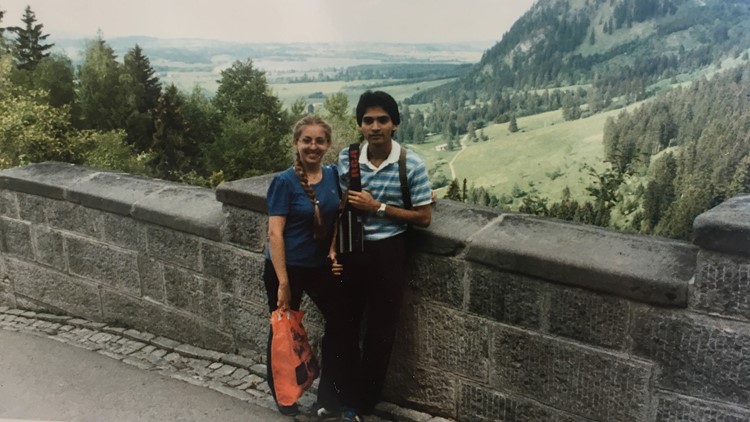

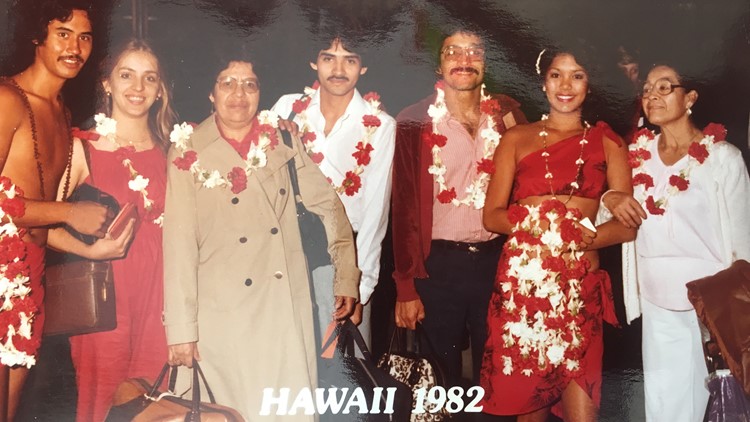

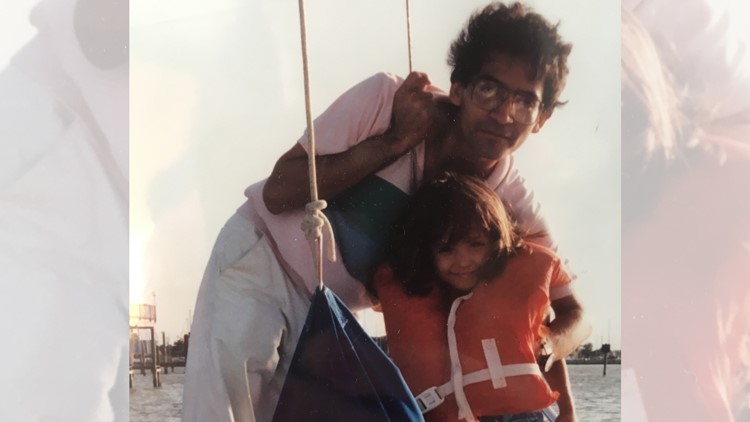

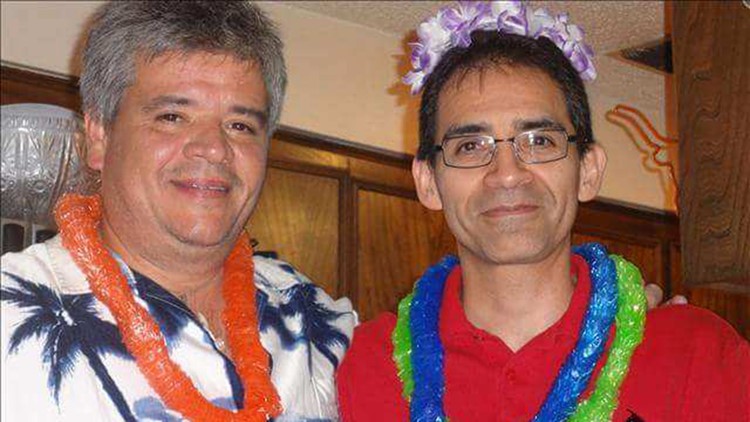

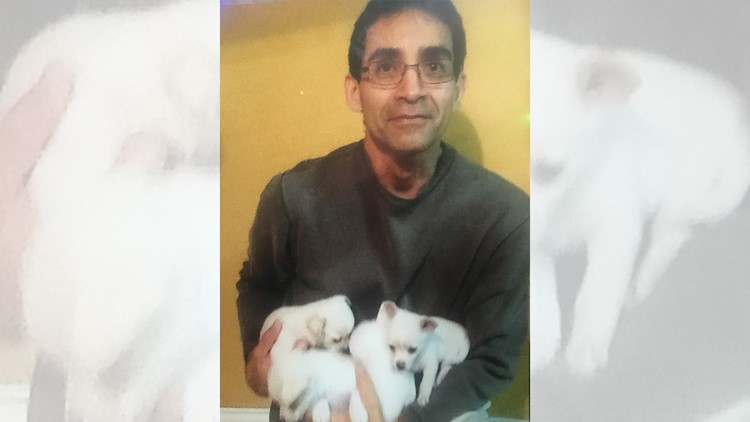

Photos: Jim and Sandra Melgar

Photos: Jim and Sandra Melgar

Sandra declined Jim’s advances for weeks. Finally, she agreed when he asked her to join him and a group of friends to go ice-skating, reasoning there was no harm in hanging out with a group of people. Only Jim had set the whole thing up. When Sandra arrived, it was just Jim and his best friend, who mysteriously disappeared after Sandra arrived. Jim used his teenaged-boy charm and terribly bad jokes—which later in life became known as “Jim jokes”—to win over the girl he was smitten by. Sandra loved that he was funny, smart and thoughtful; he loved that she was smart, down to earth and wasn’t stuck up. Soon they were inseparable, and two years after graduation, in 1980, they married in a courthouse wedding in downtown Houston.

In the Jacuzzi that night, Sandra and Jim spoke about their years together and plans for the future, she later told investigators. They wanted to sell their home and travel the world—to the Grand Canyon, Ireland, and to see the Northern Lights. Jim only had five months until his retirement as a computer programmer with the Houston Independent School District. They discussed buying a beach house where they would ultimately settle down once they finished their travels. As they spoke, they took turns massaging one another. They had sex.

After two hours in the Jacuzzi, by Sandra’s later estimations, they heard their dogs barking in the backyard. Jim grabbed a towel, slipped on Sandra’s slippers and walked out of the bathroom to let them in. That was the last time she says she saw her husband alive. She woke up some 15 hours later tied up in her closet—her hands and feet bound, muscles aching, underwear soiled—with no signs of Jim. Again, she heard dogs barking. This time there were voices coming from inside her home. She screamed.

III.

Herman Melgar stood outside his brother’s home just after 4:30 in the afternoon questioning why no one was answering the door. Jim had invited Herman and his family over for dinner days before, but now neither Jim nor Sandra were answering their phones or the front door, which Herman found odd. Jim’s black truck was parked in the driveway and an open garage door showed Sandra’s silver car parked inside.

Herman told his family to wait at the front door as he walked to the backyard and peeked over the fence. Jim, always the handyman, was known to stay busy with home-improvement projects, as noted by the plastic tarp hanging from a pergola at the back porch that he had been painting. Herman walked back to the front yard and decided to try the laundry room door inside the garage. If that didn’t work, he reasoned, he and his family would leave. But the door was unlocked, and he let himself in. The house was dark and gray and stuffy. All the blinds were closed. The dogs barked and jumped as Herman opened the front door. His daughter, Marissa, recalled an eerie feeling walking inside. “There’s just something not right,” she would later say.

That’s when they heard muffled screams.

Herman ran to the back of the house and found a large chair propped against the closet door in the bathroom; inside, Sandra was laying on the floor in a black satin nightgown screaming for help. Herman and his wife, Maria, tried to remove the bindings around Sandra’s arms and legs, but they were wrapped too tightly. Herman grabbed a pair of scissors from the bathroom. Sandra cried, “Where’s Jim? Where’s Jim?” She had bruises up her arms, including an especially dark bruise on her left bicep. Once free, she walked into the bedroom and saw Jim’s feet sticking out of the closet. She ran to him and checked for a pulse, though it was clear by his pale, cold, naked body that he was dead. Sandra covered him with a blue jacket before Maria escorted her back to the bathroom.

Sandra was crying hysterically when paramedics arrived, so much so that she couldn’t communicate with Stephanie Roberts, the first paramedic on scene. In a report filed by Roberts, she noted that Sandra “remained in a state of shock and had periods of crying” and that she “had no sense of time and last recalls a time of about 1:00am this morning. (She) did not realize that (it) was evening time and approx. 15 hours had passed.” Police took pictures of Sandra’s hands and arms and noted the bruising on her arms and bicep, also a small scratch on her left thumb. There didn’t appear to be any blood on her. Sandra told police that after Jim left to let the dogs in, she got out of the bathtub and walked into her closet to get dressed. “The next thing I remember is waking up at an unknown time in the closet,” she told police. At one point, she said, she woke up and screamed for help but must have fallen back to sleep because she had a seizure.

Sandra suffers from a series of health problems, including Lupus, an autoimmune disease that causes the body to attack itself; rheumatoid arthritis; and grand mal seizures, a disorder that leads to a loss of consciousness and violent contractions. Because of her seizures, Sandra resigned from her job as a licensed vocational nurse, believing she could no longer work effectively. In the weeks before Jim’s murder, Sandra told police she had auras, a symptom she described as a warning of an upcoming seizure. When she has a seizure, she told police, it’s common that she sleeps for hours and she wakes up confused, disoriented and is often in a lot of pain.

“When you come out of a grand mal seizure, you don’t remember a lot of stuff—you don’t remember going into it, you don’t remember what you were doing,” Sandra said from prison. “And then, even when you do come out of it, usually I’m asked questions like, ‘What’s your name? Where are you?’ And I can’t answer those because you are still completely confused.”

As crime scene investigators combed through the house, Sandra was taken to an interrogation room at the Harris County Sheriff’s Office. The room was small with high ceilings and white walls and was shaped like a box. Sandra sat in a maroon chair with wooden arms. Her hair rested on her shoulders and covered her black robe. She wore blue jeans and striped socks. A cane was leaning against an arm of her chair. She complained it was too cold.

Timeline: The case against Sandra Melgar

Sheriff Sgts. Shawn Carrizal and James Dousay spent the next three hours questioning Sandra about the 36 hours leading to Jim’s death. Sandra was soft-spoken and complained the side of her head hurt. With some details she was very specific: she took her boots off in the bedroom, undressed in the bathroom, recalled what they talked about in the Jacuzzi. With other details, she struggled to remember: she’s unsure what time they got home from dinner, at first saying midnight before claiming 10:30 or 11. She first told investigators Jim was gone 15 minutes to let the dogs in before she got out of the Jacuzzi, then later said it was about five minutes. “I don’t keep track of time,” she told them. “I’m just guessing. I don’t know.” When Carrizal asked about their plans for the future, Sandra leaned forward, buried her face in her hands and began to cry. Carrizal questioned the possibility that she killed her husband.

“So we work hundreds and hundreds of murders, okay? And sometimes we work cold-blooded killers that just are on the street, they would kill somebody for nothing,” Carrizal told her. “Then sometimes we work murders that they’re in an argument and something happens, okay? There’s two different types of people, you understand? Because if you’re arguing with somebody and lose it, your temper, an argument happens.”

Sandra cuts him off. “That’s not what happened. But I think I’m gonna stop talking about this. I think I’m gonna need a lawyer, ‘cause I know how this works.”

Dousay encouraged Sandra to take a polygraph test, which she ultimately declined, telling him she was too nervous, shaking, cold and didn’t want it used against her. Her refusal irked Dousay, who appeared to take it as Sandra had something to hide. (Dousay declined an interview request through the sheriff’s office for this story; Carrizal didn’t return requests for an interview.)

As the interview continued, Dousay told her: “We’re gonna find out everything about you. We’re gonna find out everything about your husband. We’re gonna talk to everybody in your neighborhood. We’re gonna talk to everybody that you’re related to. We’re gonna learn everything.”

“That’ll help you look somewhere else, too, ‘cause it wasn’t me,” Sandra said.

Dousay continued to question if she and Jim were having any marital issues.

“No problems?” he asked.

“No,” she said.

“No arguments? Has he ever messed around with somebody else?”

“No.”

“He ever accused you of doing that—have any reason to do that?”

“No.”

When Sandra told him she planned a trip to San Antonio to visit family without Jim, Dousay again probed her about any issues.

“You and him maybe weren’t getting along or what?” he asked.

“No, we all got along; everybody gets along,” she said.

“He just decided to stay with the animals, huh?”

“Sometimes he does that if he just wants to.”

By the end of the interrogation, the detectives’ frustration at Sandra’s lack of memory was clear. Wasn’t it ironic, they asked her, she could black out the moment her husband, who she said she loved dearly, was being brutally stabbed feet away in the bedroom? How did she not hear his screams?

“I need you to help me on this,” Carrizal told her. “Can you help me? I need you to help me. Sandra, can you help me?”

“I didn’t hear anything,” she said, her face buried in her hands. “I didn’t hear anything.”

Carrizal continued: “I need help, Sandra. Please help me. Screaming after screaming—he’s in pain. I need help. Help me, Sandra. Help me. Tell me. Your husband’s a nice guy. He went through a lot of pain. Help me, Sandra. I need help. Please help me, Sandra. Sandra, help me. Sandra, I need help.”

“I didn’t hear anything. Just stop already,” she said.

Carrizal and Dousay walked out of the cold, boxed room. With her face buried in her hands, Sandra cried. Carrizal would soon call the Harris County District Attorney’s Office to file murder charges while she was at the station, crime scene investigators still processing her home. The DA’s office declined those charges, citing a lack of evidence.

IV.

News of Jim’s murder spread quickly through their quiet neighborhood. Christmas lights that illuminated the otherwise dark cul-de-sac were drowned out by red-and-blue police lights as officers cordoned off the street. Neighbors gathered outside talking amongst themselves, speculating about a deadly home invasion as investigators processed the scene. Many residents worried that the would-be robbers might return. Some went as far as installing cameras and floodlights on their own homes to enhance security.

The Melgars were known by neighbors as a quiet couple who mostly kept to themselves. Occasionally they’d see Jim out working in the yard or see Sandra pulling in or out of the garage. Interestingly, the night of the murder, one neighbor recalled working in his garage until 1 in the morning and didn’t recall anything suspicious happening on the street.

“To be honest, if anybody was gonna get robbed, it would probably be me, because the garage door was wide open, I’m there—it was just me, messing with my stuff. If someone were gonna come down and try to rob somebody, they’d be like, ‘Look at that dude. Let’s just go in there, tie him up and take all his stuff,” the neighbor said.

Two days after the murder, Lizz met with Carrizal and Dousay. She told them about various things that were missing from the house: a TV from the bedroom, Sandra’s medicine bottles of hydrocodone and phenobarbital. Lizz had earlier alerted detectives to a backpack with a gaming system and games that was left in the garage. She told them about her mother’s seizures and health problems. “She’s in quite a fragile state right now,” she told them. “It seems that she’s undergoing some post-traumatic stress, as well. I mean, maybe something will be jogged in her memory later. It’s hard to say.”

Ultimately, she said nothing came from it. She made follow-up phone calls, told them about damage done to one of her parent’s rental homes. Eventually, Lizz said they stopped returning her calls. She and Sandra weren’t given any information about the investigation.

A year and a half later, in July 2014, Sandra was quietly indicted for Jim’s murder by a grand jury. Grand jury proceedings are kept secret under state law, so it’s impossible to know what was said and what evidence was presented during those proceedings. Her case moved slowly even after she was charged. It passed through at least four prosecutors in the district attorney’s office over the next three years until it found its way to Colleen Barnett around May 2017. Barnett had recently rejoined the DA’s office in January that year after a four-year hiatus when Kim Ogg was sworn into office.

Over her 24-year career, Barnett’s developed a reputation as a hardworking and fair prosecutor, according to both attorneys who have worked with and tried cases against her. She’s tried more than 70 murder trials in her career, including the capital murder case against Suzanne Basso, a woman convicted and later executed for murdering a mentally disabled man by luring him to Texas on the promise of marriage.

Barnett knew Sandra’s case was difficult to prove: there was no obvious motive, no confession and no direct evidence linking Sandra to the crime. “It was a challenging case, but one I believed in,” she says today.

During the 13-day trial that began in August 2017, Barnett painted Sandra as a cold-blooded killer who methodically planned Jim’s murder by luring him into their bedroom with the expectation of sex. Barnett told the jury that Sandra tied Jim’s feet with a gray telephone cord then took a knife and cut him from his chest up to his neck. (Barnett made a big point about a bag of sex toys found on the bed. Sandra later said the bag was a gag gift from a friend.) Barnett conceded she couldn’t point to a clear motive why Sandra killed Jim; instead, she offered various theories about Jim’s life-insurance policy with HISD, or that Sandra wanted out of their marriage, but as a Jehovah’s Witness, her religion doesn’t allow for divorce.

Sandra’s lawyer, George “Mac” Secrest, a well-respected attorney in his own right, painted a different picture of the frail-looking woman seated at the defense table. Secrest told jurors Sandra was the victim of two investigators who had their minds made up within two hours of arriving at the crime scene—as proof, he said, by their attempt to file murder charges as crime scene investigators still processed her home. Secrest stressed the lack of physical evidence—her blood wasn’t found anywhere, there were no cuts on her hands—linking Sandra to the crime. Secrest offered his own theory: Sandra was the victim of a home invasion, who was hit in the head and tied up in her closet, and intruders killed her husband.

To jurors, watching Barnett and Secrest go head to head in the courtroom was like watching a boxing match featuring two heavyweights. As the attorneys fought, Barnett landed a significant blow with the help of Celestina Rossi, a blood-spatter analyst and crime scene reconstructionist with the Montgomery County Sheriff’s Office. Rossi testified that the crime scene didn’t match that of a home invasion: there were no signs of forced entry, dresser drawers weren’t scattered throughout the bedroom, even pointing to a candle on Jim’s nightstand that was still lit—a sign, she said, that showed there was no struggle near the closet where Jim was killed.

Rossi testified that all the blood was mostly contained to the closet, except for the with spatter on the back of the chair, the white medical stool and those speckles of blood on the comforter. That spatter, Rossi said, likely came from when the artery near Jim’s thump was cut. Rossi agreed with the medical examiner’s report that all of Jim’s wounds were defensive, noting his loaded handgun inches away from his body that appeared untouched in the closet.

“You’re never going to shoot your spouse, even if she’s coming at you with a knife. You’re going to try to disarm her,” Rossi said. She agreed with Barnett: Sandra murdered her husband.

After eight hours of deliberation over the span of two days, the jury of eight men and four women found Sandra guilty of murder and sentenced her to 27 years in prison. She faced up to 99 years. “We figured at that point she would be in her early 70s and maybe have a chance to see her grandchildren,” the jury foreman would later say, speaking from his home a year after the trial on the condition his name was withheld. “So, it was a humane decision, frankly. Do we think this woman is a threat to society? None of us thought that.”

Sandra shrieked and nearly collapsed into her seat when District Judge Kelli Johnson read the verdict. The courtroom was filled with supporters who believed the trial was a formality to prove Sandra’s innocence, many of whom never gave any thought that she would ever be found guilty. After weeks of trying to convince Sandra all would be fine—perhaps an attempt to keep their own up spirits, too—suddenly everything wasn’t, and it was as if they spent the past three weeks lying to their loved one. As Sandra was led out of the courtroom, wearing a red blazer and using a cane, she stopped and hugged Lizz one last time. When they let go, Lizz collapsed to the courtroom floor.

“I just remember the room spinning and I felt like I was completely alone there. … I think everybody expected the jury to return a not-guilty verdict and it was just—I don’t even have words to describe it,” Lizz said. “I just felt completely lost and devastated, because not only had I lost my dad, and not only had this person gotten away with it, but now my mom is paying the price for it. And I’ve lost both my parents to a justice system that got it completely wrong.”

Sandra’s supporters focus much of their anger towards Barnett, who, they say, twisted Sandra’s words, used her religious beliefs against her and concocted an asinine story that sent her to prison. The jury foreman, however, said Barnett’s story made the most sense. He pointed to Sandra as the one at fault. Her story didn’t add up, he said, citing her police interrogation where she changed her story about the time they arrived home and how long Jim was out of the Jacuzzi before she went to her closet. He felt her seizure that night was contrived, too, citing Sandra’s medical records that listed her seizures as stable and documents that showed when Sandra visited her neurologist after the murder, she made no mention of the seizure she claimed to have had that night.

“The more you started listening to the things she said, the more you realized they didn’t make sense,” the foreman said, who stands by the verdict. “Every step of the way when you really peel back the onion you realize that she is lying. I would love to be able to believe her, but the evidence says otherwise.” Admittedly, he adds, “We’re people. Could we be wrong? Of course we can be. I don’t think we are.”

A month after the verdict, Secrest filed a motion for new trial, detailing in an 88-page brief how Sandra was convicted based on an “inept investigation,” done by investigators who were “clearly theory driven,” and with “insufficient” evidence to support a guilty verdict.

“The prosecution’s case was built on conjecture and hypotheses, which were not rooted in evidence,” Secrest later said. “Sandy didn’t kill Jaime.”

His motion was denied by Judge Johnson, sparking what could be a years-long appeals process and the last hopes for Sandra to try and prove her innocence.

V.

An aging tan urn with chipped paint sits on a wooden table behind Patsy Laurel’s blue living room couch. “That’s Jim,” Patsy says as Lola—Sandra’s tan, poufy-haired Pomeranian—hops around barking. There are markings of Sandra all throughout Patsy’s quaint home that feels warm and welcoming. Patsy’s husband, Bob, stands up from the couch. He’s tall with salt-and-pepper hair, wearing a blue Astros shirt—fitting because the Astros are playing on TV, and the good guys are winning, he says as he extends his arm for a handshake.

Patsy and Bob have been married 34 years—only six behind Sandra and Jim, if he were still alive. That’s nothing compared to Patsy and Sandra’s friendship of more than 40 years, dating back to their childhoods growing up in Laredo.

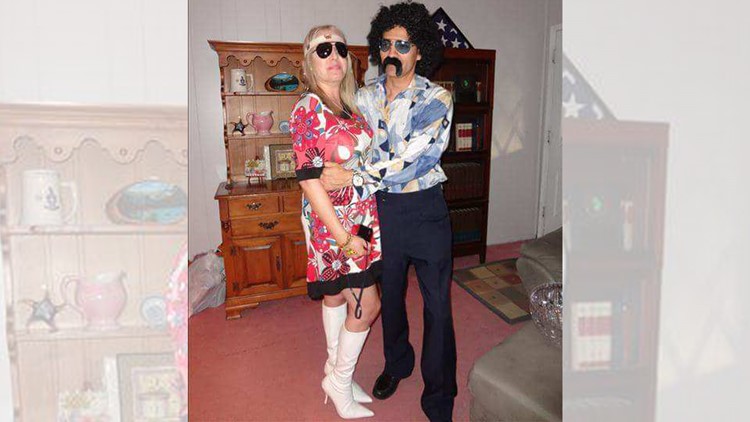

Sitting in her living room under the warm lights, Bob’s hand on her knee, Patsy smiles as she recalls the night Jim and Sandra threw a 1970s-themed party and Jim donned an afro, a fake black mustache, and blue bell bottoms with Sandra at his side in a pink-and-white hippy dress, a white headband and cream-colored boots that reached her knees. “It was pretty crazy,” Patsy said. “If you don’t dress up, you can’t come.” Patsy can still taste Sandra’s homemade sangrias and paella. These days, Bob asks Patsy to make paella, to which she scoffs; she can’t make it like Sandy, she tells him.

With all the smiles and happy memories Patsy cherishes, she also carries a deep hurt that brings tears and anger, because those memories are all she has of Sandra these days. The two often write each other—Sandra gives Patsy grief that Lola has put on a few pounds since moving in—and Patsy visits her when she can, but she still struggles understanding why her best friend is locked away in prison. Patsy cried from her seat on a wooden bench in the courtroom gallery when she heard the verdict. Hadn’t the jury witnessed the same trial she had, Patsy thought, or was she so blind that she missed something that proved Sandra’s guilt?

“How could anybody do that to her? How could anybody do something to someone so good?” Patsy cried from her living room. “Sandy would never hurt her husband. It’s insane! I am telling you. It’s insane!”

Whether or not Sandra killed Jim, the past six years have worn heavily on her. Her blond hair is graying. Her heavy blue eyes sink into dark circles. Her skin is pale under the yellow prison lights. Sandra is hopeful for her appeal, trusting her attorney will find something that will prove her innocence and exonerate her, but the process is slow. It’s been more than a year since her trial and her appeal has only recently been reinstated because of issues with the trial transcript.

Her appeal doesn’t mean she’s going to get a new trial. A panel of three appellate judges will review her trial for any errors and briefs submitted by both the state and Sandra’s defense. If she wins her appeal, the appellate court could rule she deserves a new trial if Secrest can convince the judges that any errors influenced the verdict. But the appeals court has a history of siding with jury verdicts. Sandra Guerra Thompson, the director of the Criminal Justice Institute at the University of Houston Law Center, puts the odds of a successful appeal somewhere around 1 to 2 percent.

Thompson studies wrongful-conviction cases and has watched the Melgar case from afar. Sitting in her office that overlooks a campus lawn at the UH Law Center, Thompson spoke of how the appellate process isn’t the best route to prove a wrongful conviction because the court only looks at what occurred during trial and doesn’t consider new evidence. To prove wrongful convictions, Thompson said, often requires getting outside interest involved in the case.

That’s what Lizz has spent the past year doing: speaking to nearly anyone who will listen about the injustice against her family. In a recent phone interview from her home in California, Lizz said: “My mother is sitting in prison getting minimal medical attention. I’m just worried I’m going to get a phone call saying something happened and she passed away in prison.”

Sandra has suffered two seizures in prison that Lizz knows of, one of which left her badly bruised. The Hobby Unit doesn’t have air-conditioning and prisoners must rely on fans to circulate the air. One evening, Lizz said, the power went out, leaving Sandra and other prisoners to sleep in the stale summer air.

Sitting behind a glass pane in the visitor’s center this past July, Sandra maintained her innocence. “No,” she said, her eyes hiding behind brown-rimmed glasses. Her voice softened, almost hushed, “I did not kill my husband.” She raised her hand to her mouth; she was trembling. “No, I didn’t kill my husband,” she softly repeated. She sighed and shook her head no. If not her, then who? “I wish I knew. I wouldn’t be here if I knew.” Her breaths grew long and labored. She took a moment and raised her hand to her chest; she felt a panic attack coming. She couldn’t stop shaking. She tried to control her breathing. “This is a nightmare,” she said.

She’s hopeful one day she’ll be free, either through her appeal or parole. She’s eligible in February 2031, when she’ll be 71. She hopes to see her grandchildren grow up. She’s still adapting to her new routine of early wake-ups for breakfast, the long walks to the medical center. She enjoys reading and writing letters to family and friends, which keep her spirits lifted. The prison doctor is working to correct her dosage to her Lupus medication, which makes her feel sick. During a recent visit, the doctor encouraged her to write to the warden and the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, which oversees all the state’s prisons, and ask to be moved to a medical unit that can better treat her conditions. That request was recently approved. She’s now at a medical facility in Dickinson, a small town near the coast about 30 miles south of Houston. Sometimes it’s all enough to distract her from her new life, though Jim is never far from her mind.

Follow Grace White and Matt Keyser on Facebook.

More about the case

Timeline: The case against Sandra Melgar

Photos: Jim and Sandra Melgar