DALLAS — Thirty years later, Carrie Krejci still remembers his eyes.

"I never knew what he looked like," Krejci said, "except the color of his eyes."

In 1985, a man crawled through her apartment door in North Dallas and attacked her.

"He came immediately to my bedside, and he turned me over, and he wrapped what felt like a leather strap around my wrist,” she said.

He sexually assaulted her. Then he threatened to kill her.

"I was crying so bad and sobbing that it really bothered him," she said. "He had a gun to my head, and he said he would kill me if I wouldn't stop sobbing."

Eventually, he left.

That's when Krejci called police and went to a hospital, where medical professionals collected DNA from her.

But decades then passed, with Krejci still having no idea who raped her.

“I just knew that I would, until I took my last breath, be searching for him," she said.

At the time of her rape, DNA testing wasn't around. It wasn't until technology advanced that law enforcement came up with a national database called the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS), which is where genetic profiles from crime scenes, convicted offenders and missing persons are stored.

Now, when police get DNA from a crime scene, they run it through CODIS, looking for a match.

In 2003, Dallas police finally ran the DNA from Krejci's rape exam through CODIS.

The results, however, didn't match her expectations.

"There was nothing in CODIS to match my perpetrator," Krejci said.

But police did find something.

The system showed whoever raped her had also attacked three other women in Dallas -- and two more women in Shreveport.

And, years later, when forensic genetic genealogy would eventually come along, they'd find even more.

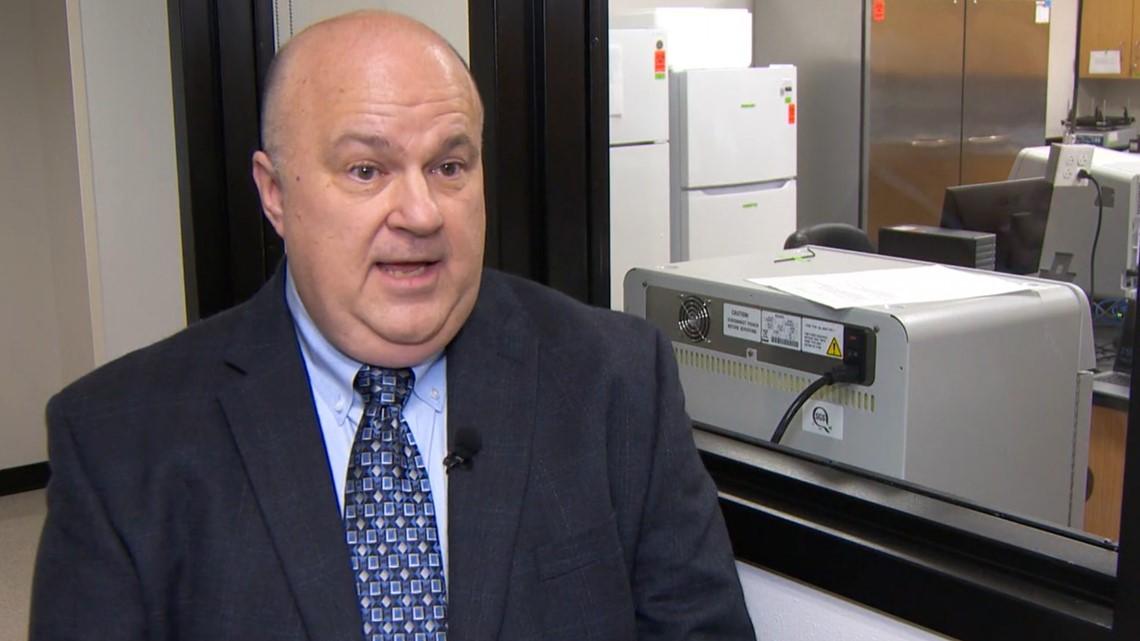

"When we use the DNA genealogy, we are searching databases to find individuals that share a high proportion of DNA with you," said Dr. Michael Coble, who runs the DNA lab for University of North Texas Health Science Center in Fort Worth.

In other words: Genealogists use family tree DNA connections to match a relative to a suspect's genetic profile, helping law enforcement identify potential leads.

"We take that information, and then we start combing through publicly available records like we would on any other investigation," said Dallas FBI Special Agent Randy White, who investigates cases using genealogy. "And [we] try to find connections where that person could possibly have been at the time or location of the offense."

Limited access

To be clear: Law enforcement does not have access to databases like 23andMe or Ancestry.com.

If you've submitted saliva for testing to one of those companies, you can rest assured: Your DNA profile will not be shared with law enforcement – unless you agree that your information be shared and uploaded to a separate site used by law enforcement.

"We don't have access to every database," said White. "That's not how it works. It's only databases that work with law enforcement."

Reach for comment, 23andME provided WFAA the following statement: "Respect for customer privacy is paramount at 23andMe. As such, we do not work with law enforcement agencies. More specifically, 23andMe will exercise any available legal measures to object to a law enforcement request. To date, we have not released any individual user data to law enforcement."

Ancestry also sent us a statement: “As shown in our Transparency Reports (2015-present), Ancestry has not shared DNA data with law enforcement. Protecting our customers’ privacy and being good stewards of their data is Ancestry’s highest priority; that starts with the basic belief that customers should always maintain ownership and control over their own data. Ancestry will also not share customer personal information with law enforcement unless compelled to by valid legal process, such as a court order or search warrant. We also try to minimize the scope or even invalidate the warrant before complying. You can view our comprehensive privacy policy HERE.”

Still, law enforcement has been successful with matching the DNA of some suspects to the limited genealogy databases available to them.

“The technology has been a real game-changer for law enforcement,” White said.

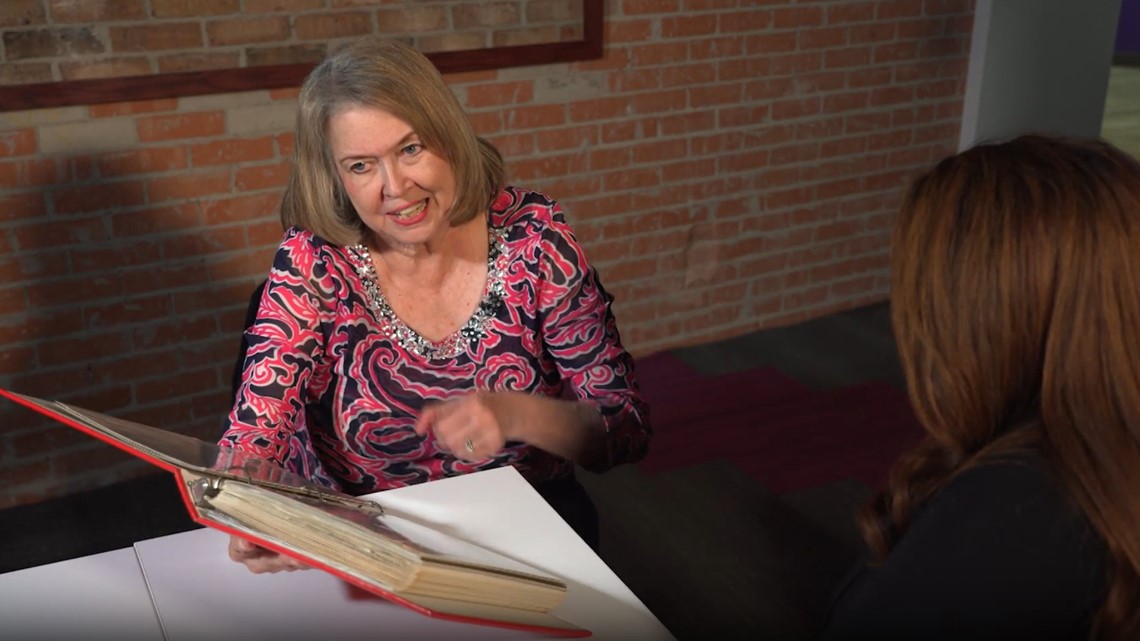

In 2021, Krejci heard about forensic genealogy and contacted the Dallas Police Department and the Dallas County District Attorney’s Office to try it on her case.

"I got an email from a woman telling me about this incredible case about an unsolved serial rapist in Dallas," said Leighton D'Antoni, the Dallas County prosecutor that looks at cold cases.

He took the case to the FBI to run a forensic genealogy profile, also called an SNP profile.

“We identified our suspect within 24 hours,” he said.

A suspect caught

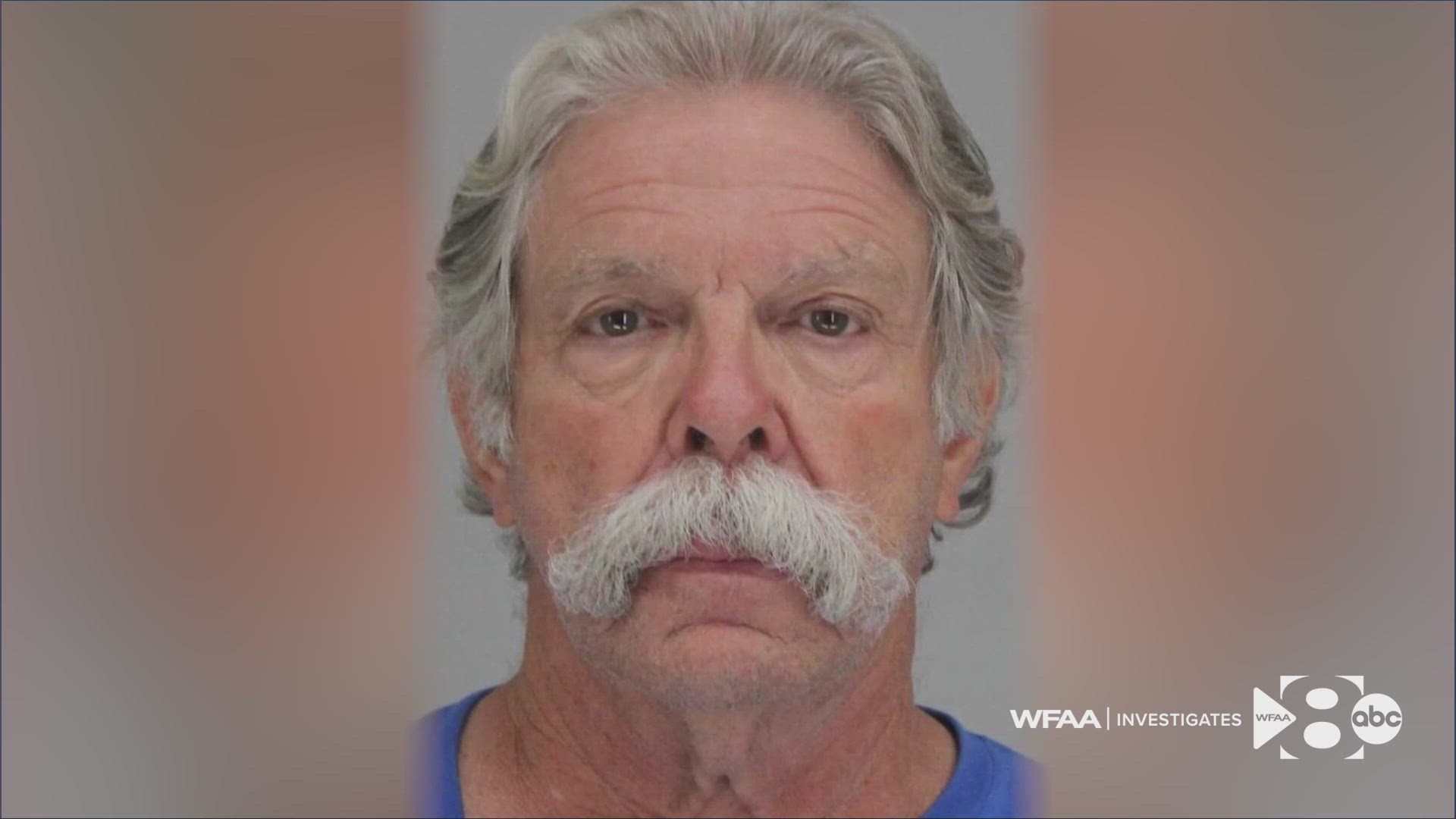

Authorities identified David Thomas Hawkins as the suspect in Krejci's case after matching his DNA to the one from her rape kit and those of the other victims.

But while the DNA hit from the genealogy search pointed to Hawkins, the match was just a lead.

"They were able to put the suspect under surveillance and get some discarded trash," D’Antoni said. "The DNA profile from that discarded trash was an exact match to the cases we knew we had – four Dallas cases and two in Shreveport. The crime lab said it was a one in a trillion chance that it wasn't him."

Krejci took pictures on the day she got the news.

"This is the day that David Thomas Hawkins was captured," she said as she showed WFAA her pictures.

That's when she started to look into Hawkins' background, to learn about the man she'd known so yearned to know more about for so long.

"I found out that he's been married three times and divorced three times," Krejci said. "In '85, when he raped me, he was married to his second wife, and she was expecting his baby."

'Biggest breakthrough'

Law enforcement says they believe forensic genealogy will help them solve not only cold cases like Krejci's, but also current cases where a suspect's DNA isn't even in the CODIS database.

“It's unquestionably the biggest breakthrough in investigative technique in my career, and I think we are just at the tip of the iceberg," D'Antoni said.

One problem: Forensic genealogy is expensive, and most departments don't have the funds to invest in it.

Soon, however, the University of North Texas Health Science Center’s Center for Human Identification Laboratory in Fort Worth will be fully accredited to do forensic genealogy on its own, and law enforcement agencies will be able to get the tests done there for free.

Krejci is thankful for that. She believes that, without forensic genealogy technology, she would never have been able to confront her rapist in court.

For her, that moment came 30 years after she was rape, during a COVID-era court proceeding in which Hawkins was wearing a mask.

"I asked him to take off his mask," she said. "I wanted to see his face."

Then she read a statement: "David Thomas Hawkins, my wish for you is that you take your last breath in prison, and that you burn in hell."

Soon after, Hawkins was sentenced to life for his crimes.

During her interview with WFAA, Krejci asked us if we could show her his most recent photo from state prison.

We obliged.

"Same eyes," Krejci said. "Same monster. That's what I see -- I see a monster. I didn't deserve that."

Email: investigates@wfaa.com