In a spartan office on Maple Avenue, there’s a clandestine cyber operation vacuuming the internet for sex trafficking data every day.

Alumni from the CIA, the National Security Agency, U.S. Navy SEALs and U.S. Air Force Special Ops work to eradicate a business that has been growing exponentially during the past decade.

Though some sex workers still walk along Harry Hines Boulevard, the commercial sex trade is largely a digital business.

Pimps have Instagram, Facebook and Twitter accounts. They sell women on a variety of websites. All this contributes to the digital information known as metadata that can be gathered about them.

DeliverFund, operating out of this Maple Avenue office, mines for digital information about the pimps and sex traffickers to share with law enforcement.

Nic McKinley founded DeliverFund five years ago, after a career in the U.S. Air Force and the CIA, where he worked in cyber intelligence.

Sex trafficking was flourishing at the time, largely because of what was happening in this Maple Avenue office. It is the former headquarters of Backpage, an international web-based sex marketing operation.

The internet sex listing service covered the United States and dozens of other countries. Backpage made it possible to put women and men up for sale in individual cities.

With an estimated annual income of $150 million, Backpage had for years evaded prosecution because of a loophole in the Community Decency Act. Backpage made Dallas a world hub for online sex trafficking.

Last year, a new law allowed the Department of Justice to raid the office and shut it down.

DeliverFund now occupies that space.

These days the room is awash in military lingo.

“Sources and methods” and “tactics, techniques and procedures” are two of the phrases one hears a lot.

“We have a target-centric methodology that is very much like we used when we hunted terrorists,” says Jeremy Mahugh, a DeliverFund co-founder and a former Navy Seal. “But now we’re hunting human traffickers.”

In a meeting room, staff meets with local police to help with a trafficking case.

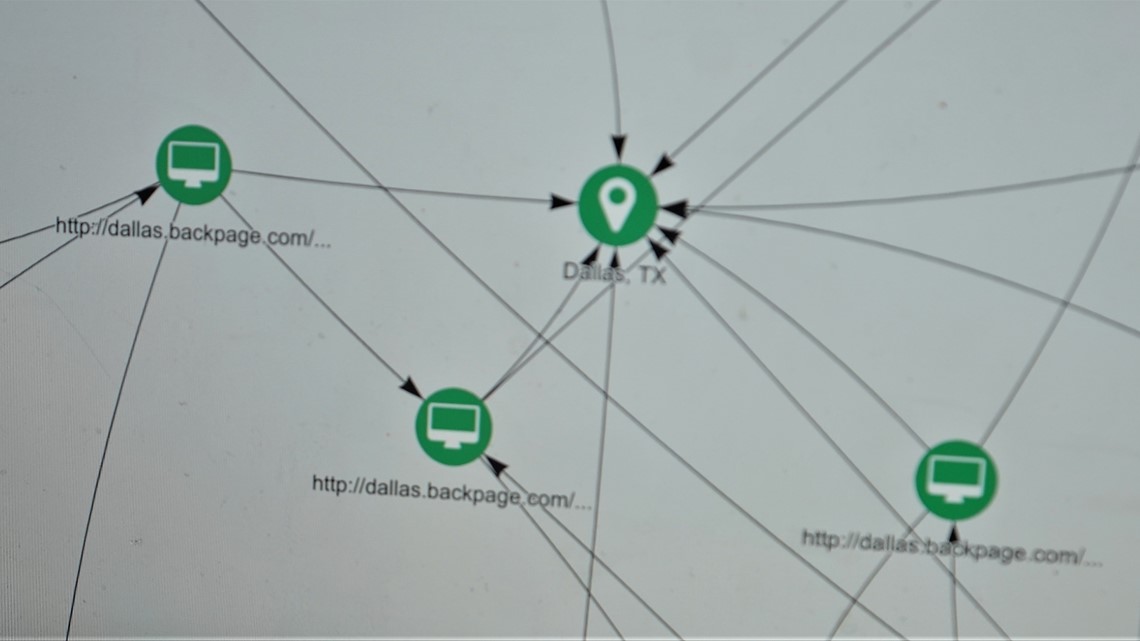

Kara Smith, an Air Force veteran and former NSA analyst, is plugging data into PATH, a proprietary software DeliverFund has created.

The Fund trains local police forces to use the software, which connects metadata gathered in Texas to trafficking cases elsewhere.

Matching data will light up on a map helping investigators connect cases. The glowing node may contain a picture of a suspected trafficker and some information associated with him or her.

“Traffickers are connected,” McKinley says. “And they’re constantly moving around.”

Smith estimates that 40% of the people selling women are other women. They begin as victims, she says, and get into trafficking as a way out of prostitution.

“And some of them, the women, are pure evil too,” says Mahugh, one of the Fund’s co-founders. “And it blows your mind because you think how can a woman do this to a child or another woman?”

The average trafficker will supervise fewer than 10 people, usually three or four. Sex bosses, especially men, can make as much as $30,000 a week, according to a study by the Urban Institute.

The pimps are eager to display their lifestyle on the internet, which helps law enforcement catch them.

“He incriminates himself all over social media with videos and other information, taking videos and screenshots,” Smith says. “I can build that out, figure out who he is, and where he is, what girls he’s trafficking and hand it over to law enforcement.”

At no charge, DeliverFund trains law enforcement how to do the same thing in seminars in its offices. The nonprofit provides three dozen departments around the country with software-equipped laptops to complete their own investigations.

Historically, it has been difficult to persuade girls to testify against the pimps who sold and beat them. The victims fear for their safety. They think prostitution is what their lives are and can’t see beyond an alternative possibility, Mahugh says.

But criminal cases are bolstered by the digital data when a trafficked victim might not be willing to testify.

Even though Backpage is dead, internet sex sales have not disappeared.

Sex businesses must now advertise on several different sites, which makes the traffickers easier to track, Smith says.

The more broadly they advertise, the more likely they are to reveal a key tidbit about their identity that will allow investigators to build a criminal case.

And using the tools provided by DeliverFund, investigators can file charges against traffickers faster. The process used to take months. Now it can sometimes only take hours, the nonprofit staff says.

The group says it has compiled more than 1,000 intelligence reports on suspected traffickers.

But, it can still take years for those traffickers to have their day in court.

“We have a long, long way to go,” McKinley says.