DALLAS — For more than four years, Larry Johnson has been cleaning the Oak Cliff Cemetery, which is less than a mile from where he was raised.

“When we first started this work back in 2019, all this was covered. It was all covered in this privet,” said Johnson. "You couldn’t see anything back here.”

Johnson walked WFAA through the cemetery, the oldest public cemetery in Dallas, sharing the stories of those buried there. “It’s a segregated cemetery. Right now, we’re walking through the white side,” said Johnson as he walked towards the Black side of the cemetery.

“Ms. Matilda, she was born in 1807. I know, tell me about it. She died in 1890. She spent almost her whole life in slavery,” said Johnson.

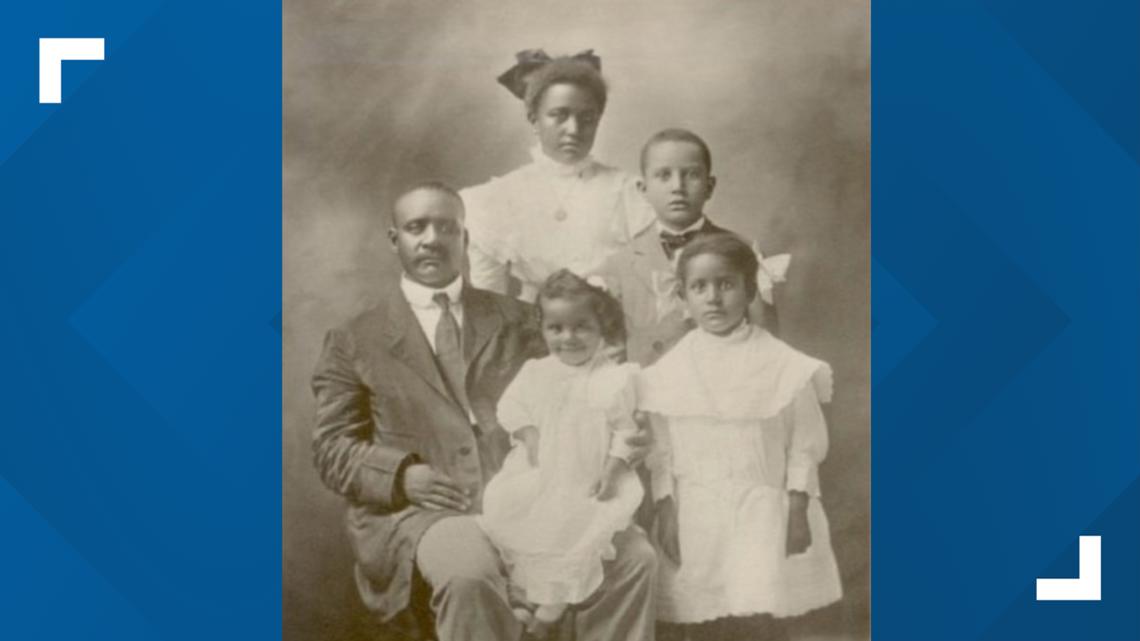

There was also the Boswell family plot. Anthony Boswell was one of the founders of what is now known as the Tenth Street Historic District. It is one of the last structurally intact Freedman’s towns in the nation. These towns are where newly freed Black people settled and lived after slavery.

In its heyday, the Oak Cliff Freedman's Town, two miles south of downtown Dallas and east of I-35, was home to a school, churches, grocery stores, cafes, funeral home, movie theater and hundreds of homes.

Tenth Street was redlined in the '30s. A Jim Crow-era practice, redlining discouraged lenders from providing loans for home repairs or purchases in Black and brown neighborhoods.

Then, I-35 was routed through the west side of the neighborhood in the 1960s, resulting in the demolition of more than 100 homes and the business district.

The Tenth Street Historic District was designated a city of Dallas Landmark District in 1993. It remains the largest, most intact Freedman's town in the country.

Larry, known as Mr. Tenth Street, serves on the board of trustees of the cemetery, on the neighborhood task force, and is involved with Remembering Black Dallas, among other organizations.

“They built institutions like schools, churches and businesses that they could pass on to future generations,” said Beverly Davis, Remembering Black Dallas Vice President.

WFAA met with Davis on the steps of the Greater El Bethel Missionary Baptist Church. It is the last standing church in the historic district.

“It’s not just Black history. It’s American history. It tells the story of what happened in our country after the Civil War,” said Davis. “This Freedman’s town here in Oak Cliff is but one example of how they threw themselves into making a good life out of an area that may have been rejected by others.”

To help understand the story of the town, community members along with Kinkofa founders, Jourdan Brunson and Tameshia Rudd-Ridge, and SMU Researcher, Katie Cross, have been tracking the changes to this area through geographic information systems or GIS mapping, alongside historical maps, aerial images, U.S. Census and city directory data.

“When you get on the road and you get on the Google map. That’s GIS,” said Cross. “What we’ve done is take historic maps and put those into the software and done this thing called georeferencing. It’s basically looking at the old maps and looking at the current landscape.”

Cross says it's the personal artifacts that bring the history to life for her.

"It's just the little things, the every day things, that really bring history to life," she said.

Kinkofa is a digital family history and genealogy platform that provides resources to Black families to document and preserve their history.

Cross, who'd been involved with Remembering Black Dallas, got involved in the project last year after hearing about a Library of Congress grant Remembering Black Dallas and Kinkofa won last year.

"I was already doing some mapping for my dissertation that looks at what Tenth Street looked like through the decades and also sort of analyzes how infrastructure impacted the landscape, and so I was really excited to be able to work with the community on a whole other level," Cross said.

They have also been incorporating oral history passed down through generations of families who have lived there. Cross said changes such as Clarendon Drive, Interstate 35, and discriminatory policies led to homes and businesses being destroyed.

“It’s really awful what’s happened, but at the same time, when you look at the past, it really provides us with awesome ideas for the future,” said Cross.

They are letting technology and history come together to drive the community forward. “It’s not lost. It’s not vacant. It is full of memories,” said Cross.

“It empowers the people of the community to realize that those who came before them were able to accomplish great things through sacrifice and hard work. Knowing that gives them the strength and resolve to fight for change and for continuous improvement in their communities,” said Davis.

Johnson called it unmasking history. “It’s helping to help families put together pieces of a puzzle in their family heritage,” said Johnson. That is why he has been doing his part by uncovering the names of those at the cemetery.

“I’m a descendant. To do this for the Boswells or the Davidsons or the Leaches, it’s to also do it for me,” said Johnson.

Remembering Black Dallas, the Dallas Public Library and Tenth Street Residential Association are partners on the project, funded by a Library of Congress Community Collections Grant. The project will be used to create a digital museum.

To learn more about the GIS mapping project and how to get involved, click here.

Also on WFAA.com: