FORT WORTH, Texas — There are no shortage of infamous Texans that have called North Texas home.

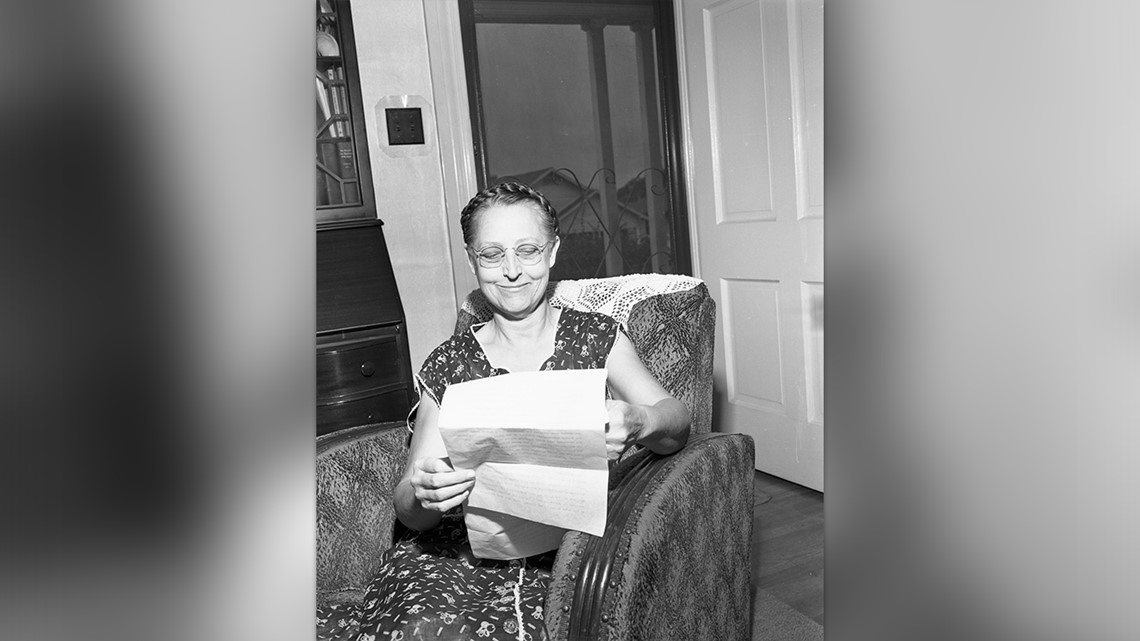

After decades of ruthless oil wildcatters, crime bosses and corrupt politicians, it may seem a tall task to find a would-be legend someone hasn't heard of here. Ada Bilbrey and her spectacles might be just the woman, though.

Some 70 years ago, she was the talk of the Lone Star state in every bar, church and drug store from the Red River to the Gulf Coast.

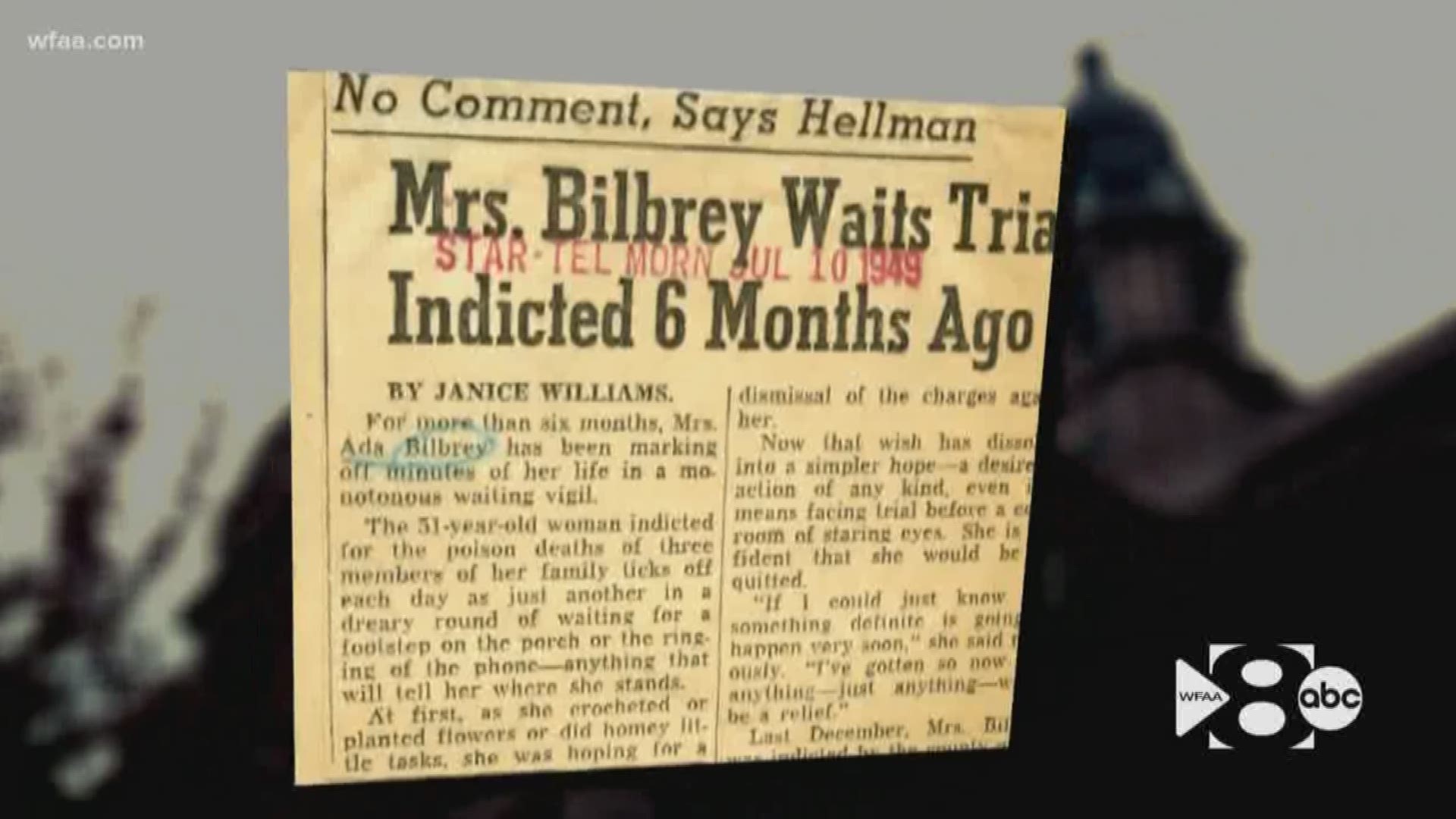

"She was the first serial killer in Tarrant County, female, and she walked!" Larry O'Neal said. "She made the front page of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram and Fort Worth Business Press 75 times in an eight month period."

Larry has a special appreciation for the mystery surrounding Ada. He runs a private museum in Fort Worth that covers anything and everyone from Amon Carter to JFK.

Still, it's the story of how Ada's husband, daughter, and son-in-law ended up poisoned to death within an eight-month period in 1948 that's something one has to hear to actually believe. "In late February, her daughter dies," said Larry. "Then in October, her husband dies, and within in an hour the son-in law."

The four lived in an unassuming home on Chestnut Avenue on the north side of town. Both men worked for a local railroad.

"All three died from poisoning," Larry insisted recently as he sat inside the museum. "In the autopsy for Richard, they found enough Strychnine to kill ten men."

As Larry tells it, the fact that three out of four people living in one house had suddenly died from poisoned pills caught the attention of authorities. Arrest warrants were drawn up, and soon 51-year-old Ada was under house arrest surrounded by 24/7 security.

"Her doctor claimed she was too sick to go in," said Larry. "So, they let her stay there."

She didn't lie in bed quietly. Press accounts from the time indicate a woman who worked reporters around the clock to gain favorable coverage, often pitting one against the other for "scoops."

Ada also was a prominent member of a local church, where many of the members insisted she was entirely innocent. "They packed the bond hearing and offered up their homes as collateral," said Larry.

Photos from the University of Texas Arlington's library archives show black-and-white negatives of packed courtrooms, worried-looking attorneys, and a smiling Ada.

There also are photos of George, Ada's husband, Dorothea, the daughter, and Richard Duke, the son-in-law, who some folks thought had been unusually close to Ada.

Dr. Cary Adkinson, a professor that studies all things serial killer at Texas Wesleyan University, looked over the case at WFAA's request. He found some glaring red flags.

"Often times with women, it isn't always who you expect," he said. "It can be the kindly, grandmotherly next-door neighbor. They're not typically boogie man waiting in the dark trying to hurt you, they're very unassuming."

He also said poison is a favorite weapon of choice for women, especially in cases from long ago when it was harder to track forensically and physically who may have done what. "It's a very deceptive way of killing, but not necessarily violent," said Adkinson.

After a new district attorney took over in Tarrant County in early 1949, the case downtown started to hit a wall. Ada passed a lie detector test, and kept insisting she was innocent. Forensics were almost nonexistent, and no one had technically witnessed Ada poison anyone.

No matter, says Larry, that there was no plausible explanation for how her three closest family members were suddenly deceased. "There are all kinds of rumors. People said she was in love with Richard, the son," he said. "But there wasn't a lot of money to prosecute, it was after the war and people were just trying to get by."

That summer, the case quietly disappeared after prosecutors determined a local jury probably couldn't look at it objectively.

But Ada stuck around, and Larry went to visit her years later in a local nursery home.

It's the only thing to do when no one else in the family will. "She's my Aunt," said Larry. "My mother's family simply did not talk about it."

When he arrived to see her, he asked the staff one simple question. "How many people come to see her? They said, 'None. You're the first!' And she didn't want any part of me," said Larry.

Despite the case being dropped, he thinks there's little doubt of Ada's guilt. "Out of the four people that lived there, only one was left standing," said Larry. "People ask me why she did it? I think she was just a bitter old woman, [but] I don't know."

Bilbrey maintained her innocence and eventually even remarried. That apparently ended in tragedy, as well.

"Her [new] husband supposedly died of an unusual accident," said Larry.

For more information on Ada's case, please visit the museum at 1633 Rogers Road in Fort Worth, or the UTA library special collection.