DALLAS — A bank is supposed to do two things: collect deposits and make loans. And many do – if you live in the right part of town.

Banking Below 30, WFAA’s ongoing investigation of banking practices, has found that south of Interstate 30, where most of the residents are Black or Hispanic, many bank branches take deposits, but those same banks don’t lend much back out to customers in the surrounding neighborhoods.

“It’s devastating and it sets you back financially for years,” said Traswell Livingston III. “You can’t catch that up.”

The first time Livingston tried to buy a home in South Dallas three banks turned him down.

“Very frustrating, very disheartening,” he said, “It makes you build up a thick skin.”

Today, Livingston owns a home in an historic block near Fair Park where, he said, many neighbors don’t trust banks.

“They don’t even … inquire anymore because they don’t even think it’s possible to get a loan,” he said.

The homeownership gap

Without home loans, there is no homeownership. And homeownership is an important way for parents to build up and transfer assets to their children, experts say. Research shows, however, that many Black families lag far behind.

According to the Federal Reserve, by age 55, the rate of homeownership among Blacks is 32% lower than it is for whites. And the homes Black families own are worth 35% less.

The disparity gets worse as people age. According to Brookings, by age 75, median wealth for a Black family is $46,000, compared to $302,000 for a white family.

Livingston funneled his negative experiences into a career in real estate and today he is concerned about some of his neighbors who have lived here for decades and are desperate for a small loan to keep up their properties.

“But most of them know that’s not going to happen,” he said, adding that many are forced to defer maintenance, further eroding their home’s value. “Patch it up. Close off the door. Don’t go in that room. Keep moving. Do it with cash or don’t do it at all.”

North-south disparity

WFAA’s analysis of banking data shows in the northern half of Dallas there are 296 bank branches. In the southern half, there are 55.

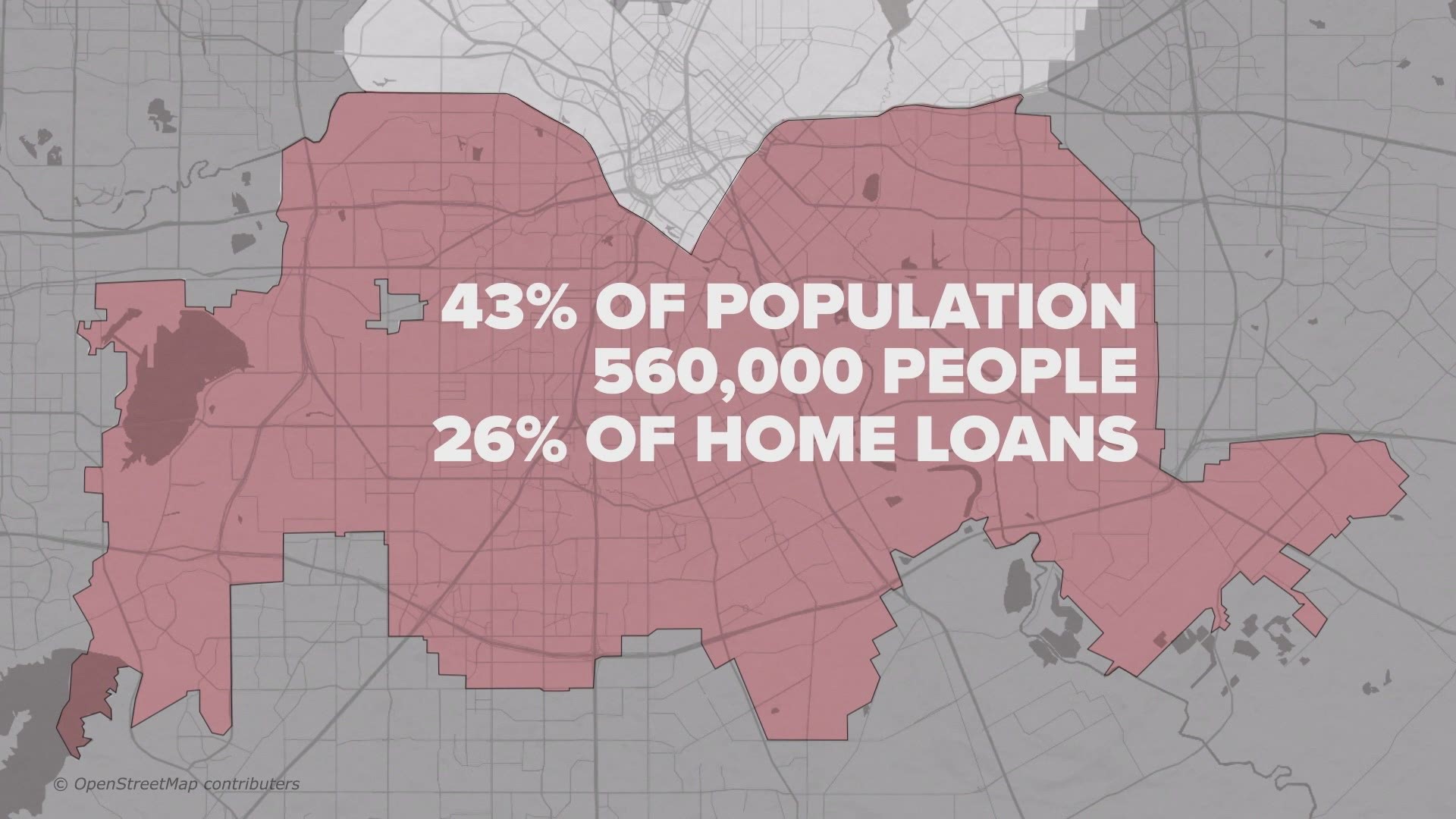

But, according to the Child Poverty Action Lab, 43% of the city’s population lives below I-30, or about 560,000 people. And our analysis shows they are only getting 26% of the bank loans.

But of the banks that do have branches in Southern Dallas, how are they performing?

Neighborhoods in DFW are broken down into census tracts. The one Livingston lives in is near Fair Park and includes a Bank of America and a Chase Bank.

We clustered this tract with adjacent tracts -- to create a large area that a bank branch might serve. Then, using federal government home loan data, which banks are obligated to report publicly, we counted all the loans the bank – though not necessarily originated from that branch – made here in 2018 and 2019.

Over two years, Chase made four home-related loans, and Bank of America made five.

By comparison, six miles away, in a census tract cluster around a Chase and Bank of America in Lakewood, Chase had 171 loans. Bank of America reported 143.

“That’s a smoking gun,” said John Taylor, a fair lending advocate and head of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition. The NCRC has assisted WFAA in analyzing government loan data throughout the Banking Below 30 investigation.

“Should banks be investing in credit-worthy borrowers in South Dallas? If they can show they can pay these loans back, that they have enough income should the banks be doing it? The answer is yes, of course. That’s the law,” he said.

What’s the overall picture for Chase and Bank of America north and south of I-30? In the neighborhoods around Chase’s northern branches, there were, on average, 102 loans around each branch. In the south, there are 32. Around Bank of America’s northern branches, the average was 67, and 23 to the south. Wells Fargo made an average of 65 around its northern branches, and 18 to the south.

In statements to WFAA, Chase wrote that it “regularly ranked first or second in southern Dallas for all mortgage lenders, and typically ranked first among banks. However, we recognize that too many people are not sharing in the region’s prosperity. In southern Dallas and within communities of color, we know we can do better…”

Bank of America told WFAA that loan data from 2018 and 2019 doesn't capture the bank's more recent affordable homeownership initiative in Southern Dallas, which has recently lent $75 million dollars to 365 low- to moderate-income borrowers and made $4 million in down payment grants to first-time buyers.

Bank of America's latest initiative "focuses on closing the racial wealth gap in Black and Hispanic-Latino communities with a focus on affordable housing, health and healthcare, jobs/reskilling and small business," the company said in a news release earlier this year. "Through the Community Homeownership Commitment, Bank of America is addressing two of the biggest barriers to homeownership -- down payments and closing costs -- which will increase access to homeownership for thousands who have historically not been able to own a home."

Wells Fargo told WFAA that, on its bank exams, its distribution of loans to low- to moderate-income borrowers "exceeded the aggregate lending and received a rating of “good,” despite affordability challenges…" in Dallas.

"Wells Fargo remains committed to helping the southern Dallas community and others thrive with a variety of offerings to address low- to moderate-income (LMI) communities and small businesses," the bank wrote in a statement to WFAA.

“If the regulators just raised the question, ‘Gee, you only made four or five loans in all South Dallas, what the heck is going on here?’ – that’s what examiners, regulators are supposed to do,” Taylor said. “They won’t do it, unfortunately, unless someone makes an issue of it.”

Big banks are regulated by the Office of Comptroller of the Currency. In a statement to WFAA, it says: “… examiners do not have the authority to require a bank to make mortgage loans or to make such loans in a specific area.” And that the localized lending data used in our story can be influenced by the level of owner-occupied housing, income level, market volatility, and population trends, the OCC said.

A call to activism

Again, the definition of a bank is a “financial institution licensed to receive deposits and make loans.” Advocates say a keyword is “licensed.” The government grants a bank the right to operate and make big profits. But in exchange, there are rules.

And they include the Community Reinvestment Act. It’s a powerful federal law that says banks are required to meet the credit needs of the entire community and reinvest in the minority neighborhoods they’ve long ignored.

“We have to confront their greed,” said Diane Ragsdale, a former Dallas city council member with the Intercity Community Development, a nonprofit that helps working families in low- to moderate-income (LMI) neighborhoods achieve homeownership.

“The law was created for a reason – banks refused to lend to LMI communities,” Ragsdale said. But she acknowledged the law doesn’t work unless the public knows about it, and acts. “And that’s where a movement comes into play,” she said.

She said people need to understand their roles as advocates for themselves and their neighborhoods, and banks need to understand – and take seriously – their roles under the law.

“What is your role? To sit there and do nothing? Just sit there and receive deposits. No!” Ragsdale said. “Your role is to get out there and develop relationships with people – communicate with the people and determine what I can do to meet your lending needs.

"We’re more than willing to publicly embarrass you because you have disrespected us and our needs," she added.

Email dschechter@wfaa.com