I heard a rustling behind me, turned around and there was an eight-point buck--chest heaving, still as stone—about fifty feet away. Two does, behind him, cautiously raised their heads and met my gaze. He’d come through a gash in a chain link fence. They’d remained inside. Inside the grounds of the Middletown Works, a steel mill covering nearly four square miles in Middletown, Ohio, the buckle in the belt of Armco steel, founded there in 1910.

It Was Like Living in ‘Leave it to Beaver’

In 1957, Middletown was declared an All-American City by the National Civic League. The anointment, bestowed on ten cities nationwide each year, was recognition of something many families living there at the time already knew. Middletown was a great place to live. “It was like living in ‘Leave it to Beaver,’ Middletown native Bob Hayden told me. “There wasn’t a better place to grow up.” 1957 was the year Jerry Lucas, one of the most famous All-Americans in Ohio State history, was hitting his stride as a Middletown high school junior. After watching a ‘Middies’ game on Friday night, girls would feel perfectly safe walking down to ‘The Jug’ by themselves for a burger.

After college, Haydn went to work for Armco, the undeniable backbone of the city, like many of his classmates. The company would lend its best and brightest to serve on school and park boards.

Armco ran its own hotel, so visiting customers would be guaranteed suitable lodgings. It brought the city an opera, astounding for a town of 30,000. It built employees a golf course, Armco Park. And at Christmastime on Main Street, Armco executives opened their Victorian homes to townspeople. Fueled by union wages and corporate pride, the place seemed like a Disneyland of the Midwest. Young men would graduate from high school and follow their fathers into a career in the mill.

I and my colleague Roy Vandiver were following the so-called ‘hillbilly highway,’ a route from southeastern Kentucky to southwestern Ohio that thousands of Kentuckians had taken in the 1960’s and 70’s, in search of the high-paying wages of industrial Ohio. It was a trail J.D. Vance took as a young man, but not of his own choosing.

Vance’s 2016 book Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis, had been a kind of Rosetta stone for the travails of low-income white America. Elegy tells a tale of a dysfunctional family in which Vance’s mother struggled through chemical dependence, poverty, and a series of broken marriages. Vance and his sister were raised by grandparents in Jackson, Kentucky, and Middletown, because their mother was not responsible enough to raise them herself. While the book is a memoir of Vance’s life so far (he is 33), a reader cannot help but trace his individual experiences to the culture of lassitude, hopelessness, and economic dysfunction that grips Appalachia. He casts a dispassionate eye on the values of many of the people he grew up with. He was able to escape that culture through the Marine Corps, a university education and eventually Yale law school. As someone who left Appalachia to merge into upwardly mobile society, Vance became a kind of interpreter for Donald Trump’s appeal in the 2016 election and made several national television appearances.

My colleague Roy and I had already been to Jackson, population 2,000, where we found unemployment, poverty, and opioid abuse. What we found in Ohio was a variation. Economics are not nearly as dire. In Jackson—Breathitt County—Kentucky, the median household income was only $25, 817, between 2011-2015 according to the U.S. Census. In Middletown—Butler County—Ohio, it was $57,540, more than twice as much, for the same period. Middletown is struggling with economics, pessimism, and drugs, to be sure, but it is also haunted by memories of the golden age of Armco, which would be difficult for any city to replicate. The worst parts of Dallas, Texas look a lot worse than their counterparts in Middletown.

J.D. Vance was born more than a quarter-century after Middletown’s All-American city award. By his teenage years in 1999, Armco was acquired by AK Steel Holdings. “AK” stood for Armco and Kawasaki (Kawasaki Industries of Japan). The two companies began a relationship in the 1980’s. But by the end of the 90’s, Kawasaki was the owner. American steel was under siege, particularly from China which was selling steel as much as 10% cheaper than U.S. steelmakers. AK had too many workers. Those high-paying sure thing jobs were harder to get, and as Vance writes, a lot of kids didn’t want to take them anyway.

AK wanted concessions from its union, in the form of job cuts and outsourcing. In 2006, the union refused to accept a new contract offer. The company locked out 2700 workers for a year, who began to lose their cars and houses. When the dispute was settled, just 1250 workers got hired back. The love affair between the city and the company faded, and 2007 AK moved its headquarters 15 miles away to West Chester, Ohio. The Armco Park Golf Course was sold a year later.

“It (the lockout) was the beginning of the end,” says Dan Diver, whose family has run Diver Garden and Pet Supplies in Middletown for five generations.

The city saw its tax revenue shrink, and basics like infrastructure repair and police protection suffered. Meanwhile, as AK was rusting, the same scourge that had Jackson, Kentucky in its fist was moving into Ohio.

Opioids.

The enormous American flag began to unfurl about a mile above Smith Park, less than a mile from old downtown Middletown. Six skydivers had bailed out over the Ohio Challenge Hot Air Balloon Festival in July. Each trailed a flag or streamer, but one released a 7800 square foot Stars and Stripes. Moms, dads, teenagers, kids in strollers—were mesmerized, at what became the event of the evening. The hot air balloons it turned out, were grounded because of the weather.

But the flag was there, and it seemed it would never land as the jumper slowed his descent rate.

So, the crowd milled around, stood in line at the food trucks, sat in lawn chairs, drank Yuengling lager, a local brew, watching the flag float down to the All American City.

And some apparently shot heroin.

The next morning, the cleanup crew found a handful of syringes.

Opioids are a part of life here.

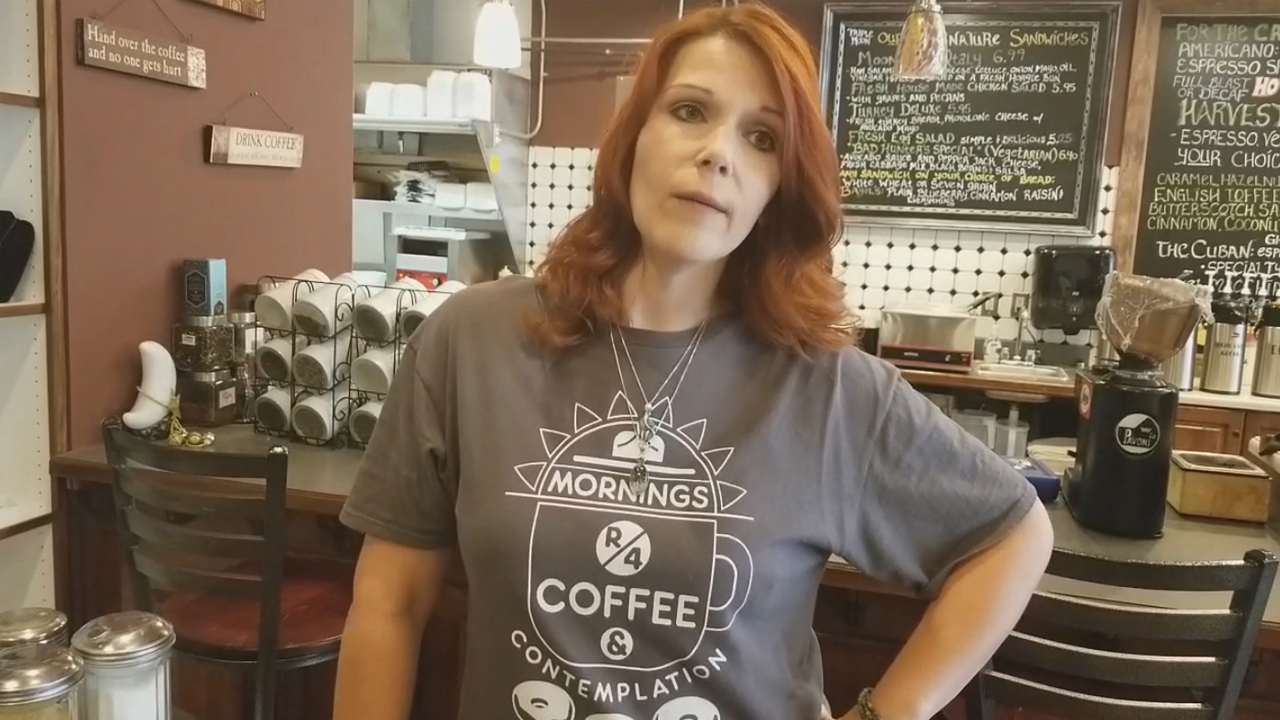

“You can’t, typically can’t go to a restaurant, drive down the street without seeing somebody with an obvious condition,” Renae Theiss, a barista at the Triple Moon Coffee Shop told me. “Needles. OD’s. People in parking lots.” Why? “A lot of it is desperation, people are depressed, it’s poverty. And I guess it’s a release.”

“If you go down to the McDonald’s on North Verity (Parkway), you’ll see lots of people OD’d,” Lt. Jim Cunningham of the Middletown Police told us. Verity Parkway, coincidentally, is named after George Verity, the founder of Armco Steel. The McDonald’s on North Verity is open 24 hours. Over several visits, we saw no one passed out there, but plenty of cars were parked outside with people in them, unconventional in a restaurant where customers usually drive through and leave or eat inside.

Middletown blasted into national consciousness earlier this year when a City Councilman proposed to limit the number of opioid antidote shots one addict could receive because the cost of the medication is breaking the city. Naxolone, better known by one brand name Narcan, can prevent an overdose victim from dying, but Middletown is spending so much on it that the councilman talked about a “three strikes you’re out” limit on Narcan doses for any one victim. The proposal never took hold. But one county north, Narcan is carried by the cops. Its problems are worse.

“You want to score some heroin, go to Dayton,” a former Ohio resident outside a Kentucky rehab center told us.

“You can’t walk down the street in Dayton without somebody trying to sell you heroin. It’s everywhere.”

Dayton is the county seat for Montgomery county where 371 people have already died of drug overdoses through May of this year, according to the county coroner. That’s more than died in all of 2016. Last year in Butler County, Middletown, there were 211 overdose deaths. Through May of this year, 96 have already died, according to that county coroner.

Broadly, there are three kinds of opiates on the street market today. Oxycontin, a prescription pain medication, is the foundation of the epidemic, but restrictions on prescriptions have driven up its street price. Heroin is much cheaper and has replaced the prescription medication as a drug of choice for addicts. Fentanyl and carfentanyl, an even more potent twin, can be hundreds of times more powerful than heroin. Dealers are blending it with heroin, but a user on the street never knows exactly what’s in the drug he or she is putting in their body, and that can be a killer. Most of the deaths, the Ohio Health Department says, are due to heroin, fentanyl, or a combination of the two. The highest death rates in the state spread along the Ohio River valley, and up Interstate 75, which runs from Cincinnati to Dayton.

In Cincinnati, Hamilton County, there were 22 overdoses on one Saturday in August. Three hundred eighteen people died of overdoses there last year. As a result, the Hamilton County Health Department contacted Adapt Pharma, Narcan’s manufacturer, which agreed to donate 30,000 doses to first responders. That follows hundreds of thousands of other doses Adapt has given to police departments across the country.

Meanwhile, back in Middletown, Sheriff Richard Jones says his officers won’t carry Narcan, and that it’s not their job to revive overdose victims.

That doesn’t prevent Middletown resident Dorothy Shuemake from carrying the antidote. Her daughter Allison died of a heroin overdose two years ago. Allison was an outlier in some ways: more than twice as many men die from overdoses as women in Ohio, most between 15 and 45. But she was typical in others: she was a bright kid who had no apparent reason to try the drug.

“I think of her every day. All the time,” she says. Mrs. Shuemake didn’t know her eighteen-year-old daughter was experimenting with heroin. “I wonder what I could have done. What if I had done this? What if I had done that?” Now she carries the Narcan in her pocketbook, goes to community meetings, task forces, and counseling sessions to try to help other families deal with the chemical steamroller crushing Ohio. She used to work for the city of Middletown. Her husband was a twenty-year veteran of the Middletown Police.

Lt. Jim Carpenter says the police force now has only 65 officers, down from 94 five years ago, the numbers declining because of lack of money. “We seized 3 grams of heroin last month, 300 grams of fentanyl,” he told us. “We only have six officers on the street, five detectives on the ground,” describing how difficult it is to crack drug distribution.

With 4,050 drug overdose deaths last year Ohio had more than any other state.

Still, life goes on, commerce goes on.

The string of countries that stretch northward from the Ohio river are slowly melding into one unbroken city from Cincinnati to Dayton.

In Middletown, ardent community boosters like Ann Mort and Dan Diver are not ready for an elegy yet.

They strive to make the city as vibrant as it ever was, sponsoring flower bed ‘bright spots,’ murals and gathering places. City Manager Doug Adkins wrestles with ways to alter the city’s housing stock to improve tax income.

Downtown, which has suffered empty storefronts, has a new wine bar, a new upscale restaurant, and the Triple Moon Coffee house, which set up shop three years ago.

There are concerts in an urban park across the street.

And in June, Dayton, whose Montgomery County had the highest death rate from drug overdoses in the United States, was named an All- American City for the fourth time.