DALLAS — As the country celebrates Black History Month, it is a time to recognize the moments and acknowledge the people who helped spur progress from times of oppression. Some businesses were once segregated by race but an Oak Cliff movie theater caused a stir of their own in 1973.

Not by showing preference to customers but to the type of movie on their screens.

The Triangle 4 Theatres, once located at the intersection of U.S. Highway 67 and S. Polk Street made the decision to only show films with predominantly Black actors on all four of their screens. According to a WFAA story archived in the SMU Jones Film Collection, the move was made to help jumpstart lagging business but created plenty of controversy among nearby business owners and the Southwest Oak Cliff community.

“If the movies go 100 percent Black, this will damage our business and our trade,” said one neighboring business owner.

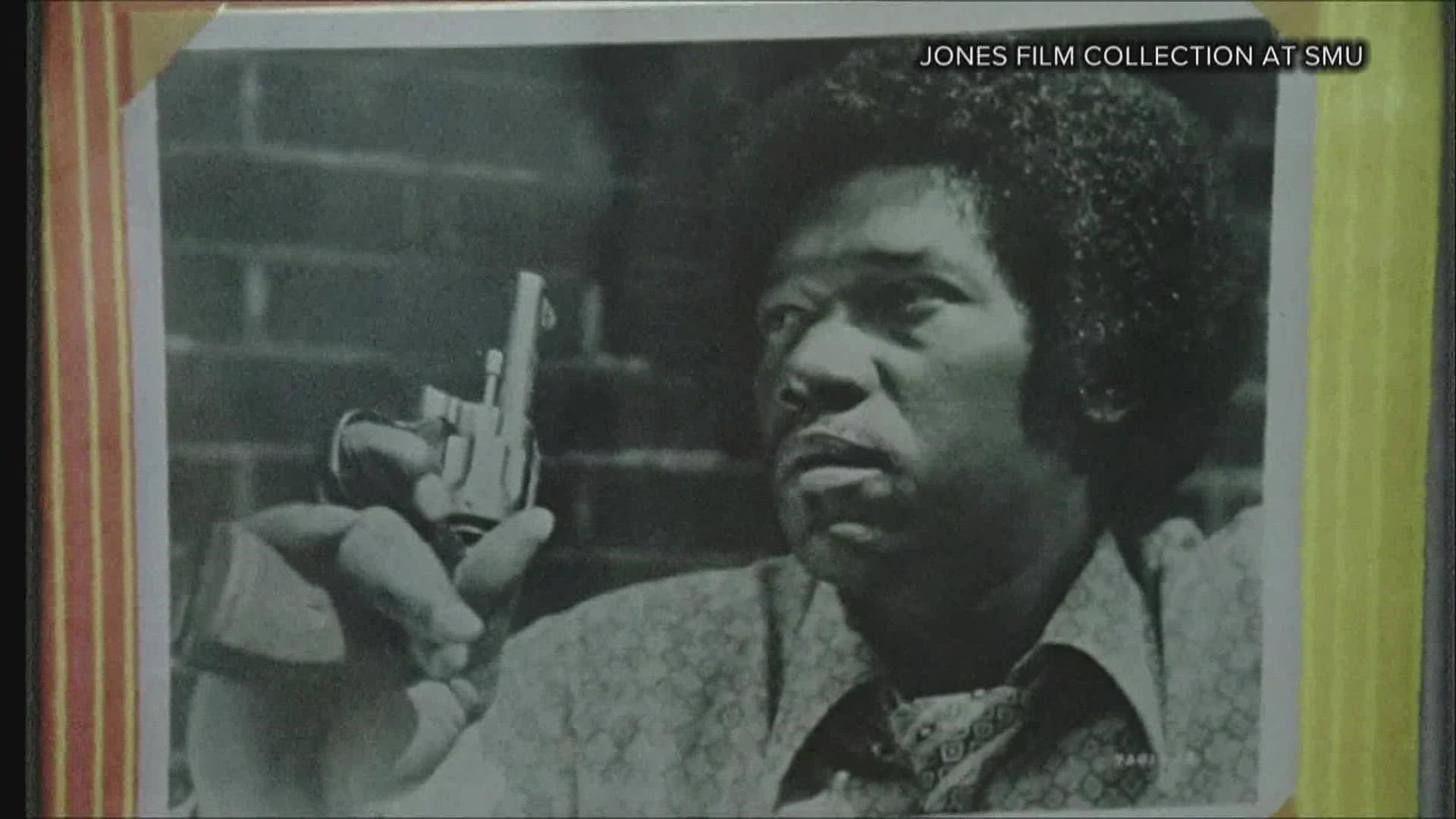

Even a Black woman attending the theatre adorned with posters from films like Shaft and Sounder wondered if an all-Black film theater was a good idea.

“Maybe they should even it out and do two Black movies and two white movies,” she said.

Watch the original story:

There was concern that any business showing preference to one race over another would be a step back towards segregation. The 1973 report cited numbers the community was 65% white and 35% minorities at the time. One man interviewed for the story said the neighborhood was happy with the “mix” of people and wanted to keep that mix stabile.

But George Keaton has lived in Oak Cliff since 1969 and now runs Remembering Black Dallas, a nonprofit preserving the history of black culture in Dallas County. He believes the desire to keep the “mix” stable was really a desire to keep more black families from moving to town.

“There was a mindset property values would decrease,” Keaton said. “This was about more than the movies being all black. It is what they felt about blacks coming into the community.”

The Black film only showings did not last long. Eventually, Triangle 4 reached a compromise and the only remnants of the theater today is a strip center, boarded up where the box office used to sit.

And that is not the only thing that disappeared.

“We called it white flight,” said Keaton. “Now (the population) has flipped greatly to nearly 100 percent minorities.”

He believes preserving the stories of the past can still provide valuable lessons on race relations and how integration and segregation can happen, even if unintentionally so.

“We can never know where we are going If we do not know where we’ve been or where we come from.”