ARLINGTON, Texas — On the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II, an aging leather trunk full of mementos at Jack Bateman's home in Arlington becomes that much more valuable. Because as memories fade, it connects him to a story he wants the world to remember.

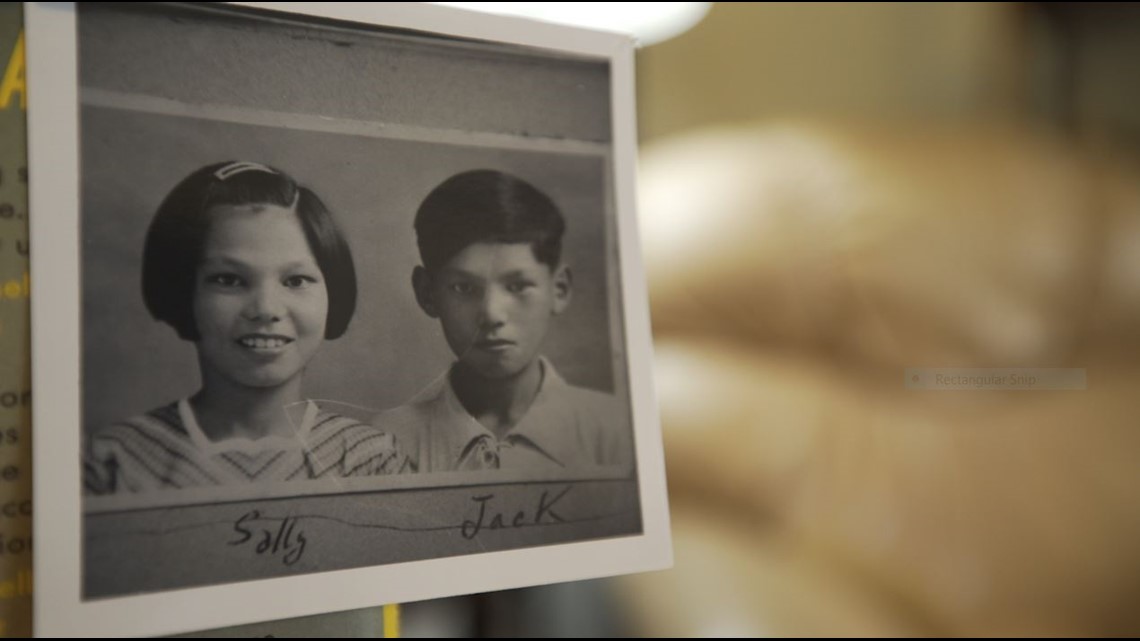

Bateman, 92, his sister Sally Morgan, 89, and their late brother Jimmy, were teenagers living in China. Their mother was Chinese. Their father was an American soldier who died from tuberculosis in 1931.

"My mother was not able to care for the three of us," Sally said.

"I feel like I'm a vessel," she said, as she and her brother sifted through the old documents and photos. "And why I am used is to tell my story."

Their story was difficult from the start. And by the time Sally was 11, Jack was 13, and their older brother Jimmy was 16, the Japanese invaded China at the start of World War II.

"War is hell," Jack muttered.

And it was hell that their mother tried to save them from by sending them to live with a Christian missionary who took them to what they thought would be the relative safety of the Philippines.

"We thought we were safe because it was under (the) American flag," Jack said.

But when they arrived, the Japanese army was already there.

"And within three months' time we were in prison camp," Jack Bateman said. "When we talk about prisoners of war, we always usually think about the military and not civilians. So we were the exception to the rule."

"And since we were Americans they told us that we needed to be interrogated for just a couple of days," Sally said. "And that's was the starting of the internment."

They became among the tens of thousands civilian prisoners of war. First, they were housed in a camp on the grounds of Santo Tomas University. And then, in the final year of their three-year confinement, at a camp called Los Baños.

"Really on a starvation diet," Jack said of the population of American citizens and other non-Japanese. "The Japanese would say they died of heart attack instead of starvation. The guy who was in charge of the camp before we got there had a dog and was his pet. And somebody stole it and ate it. And boy, was he mad."

"Los Baños camp had two barbed wire fences," Sally said. "In between the two barbed wire fence is called no man's land. If you were caught in the no man's land the Japanese shot you and then asked questions later."

But the teenagers were among the survivors because after three years of captivity, Americans helped liberate them the same day the American flag was being raised on Iwo Jima thousands of miles away.

"My fondest memory is my liberation," Sally said with a smile. She was still a young teenager when the sounds of battle came closer and closer to the camp. Women in her barracks tried to shield her by hiding her under a bed.

"I could see the paratroopers' boots. That was the most beautiful sight," she said.

They would go on to live full lives here in the United States. Their older brother passed away several years ago. And now Sally and Jack, in the time they have left, remain active in organizations committed to telling the stories of POWs and MIAs.

"We need to realize that war doesn't help anything," Jack said. "You get through one war, you go to another. And you go through another."

"I guess it's maybe because that I am so appreciative that I'm living here," Sally said of the reasons she continues to take every opportunity to tell their story. "I was given the privilege to live in a country that is free. And the story needs to be told."

Told and remembered, so that a world wrapped up in its current problems can see what freedom really means, before a trunk full of old memories slowly fade away.