DALLAS COUNTY, Texas — When COVID-19 forced life to change around the world in March 2020, there were more questions than answers. Initially, many believed young people weren't vulnerable and kids couldn't get it. There was confusion about how it spread. There were some who didn't even believe it was real.

As weeks passed, case numbers and, sadly, the number of people dying from the illness continued to rise. Businesses closed. Schools sent students home. Scientists and researchers began collecting information to tell a more complete picture of what the world was really dealing with.

One of first trends to make headlines was the data showing the virus, while devastating everywhere, had a disproportionate impact on Black and Hispanic communities.

Nearly three years later, that is still the case.

As of the end of 2022, the CDC reported that people of color are still more likely to get COVID, be hospitalized with it and die from it than white people.

But COVID-19's impact on the Black community did not create disparity; it simply shined a light on a gap that's existed for decades. Dr. Carolee Estelle, associate chief of infection prevention for Parkland Health and Hospital System, said the pandemic's impact on Black communities was not surprising.

"The disparities of chronic medical conditions is not new," Estelle said. "This has been ongoing for many years."

It's a story that was already being told in data for illnesses that have been normalized and often underestimated. We started calling them "underlying conditions" because they created complications for COVID-19, but even before we'd ever heard of the Novel Coronavirus, chronic conditions like hypertension, heart disease, obesity and diabetes were already killing hundreds of thousands of people every year.

They were also disproportionately killing Black people.

"Chronic diseases like diabetes, high blood pressure and coronary artery disease all cause mortality for patients in our community," Estelle said. "They represent a huge burden on our community as a whole, but especially in our Black and Brown communities."

At the end of last year, Parkland partnered with Dallas County Health and Human Services to release its Community Health Needs Assessment, which is basically a comprehensive report of the health issues that exist in Dallas County and with Parkland patients.

The 128-page report lays out the findings from community surveys, hospital data and health data from the county. Within this report, which includes a lot of information from 2020, is a glaring truth that Black people were already dying at a higher rate than other ethnic groups from a number of chronic illnesses that, in turn, created a greater devastation from COVID-19.

"It's the same thing every flu season as well," Estelle said. "They're [people with chronic illnesses] at increased risk of getting severe fly and getting severe flu as well, and that happens every season."

In the Fiscal Year 2021, Parkland treated 113,623 patients who suffer from high blood pressure who visited nearly 800,000 times.

High blood pressure, or hypertension, was the chronic illness the hospital system received the most visits for, and 84% of those patients were Black and Hispanic.

"High blood pressure, they call it the silent killer. Why do they call it the silent killer? Because you don't feel anything, but it can be ongoing," Estelle said.

It's also the biggest risk factor for heart disease, which is the leading cause of death in the United States, Texas and Dallas County, and has been for decades.

The report states African Americans have the highest heart disease mortality rate, which is also a trend that's persisted for years.

In fact, when looking at mortality rates for some of the more common causes of death in Dallas County, Black people outpace other ethnic groups.

In 2020, the leading causes of death in Dallas County were heart disease, cancer, COVID-19, accidents, Alzheimer's, cerebrovascular disease, chronic lower respiratory disease, diabetes, nephritis/nephrosis and chronic liver disease.

Black people had higher mortality rates for six of them: heart disease, cancer, accidents, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes and nephritis/nephrosis.

All of these conditions, except for accidents, are chronic illnesses.

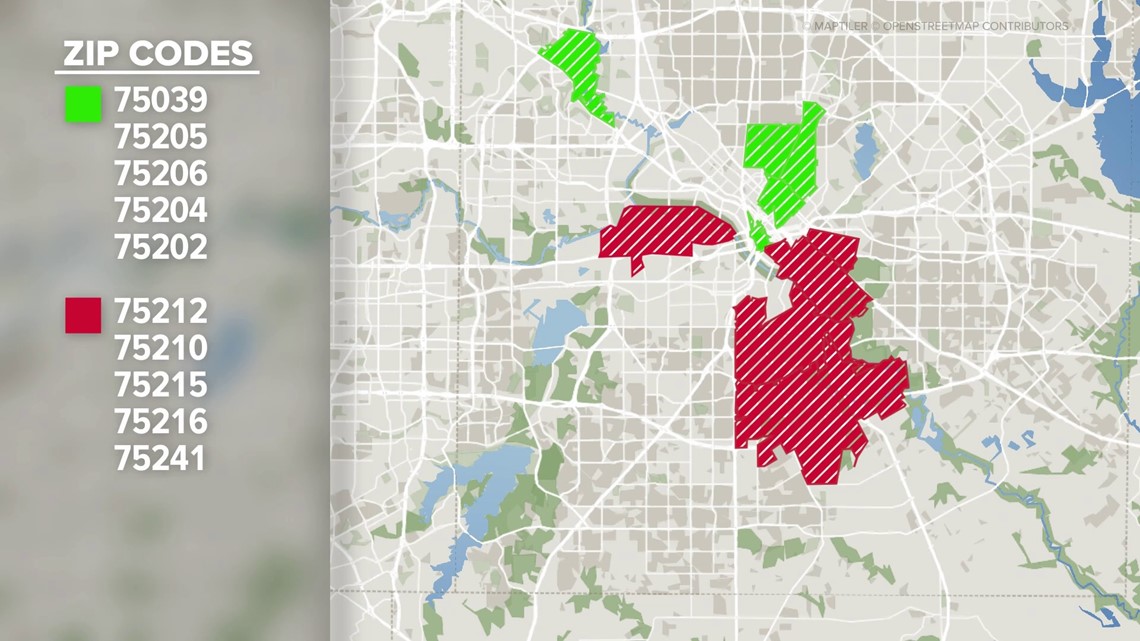

When looking at the five most vulnerable, compared to the five least vulnerable, ZIP codes in Dallas County, there's a pattern. Despite close proximity, the ZIP codes with the highest chronic disease vulnerability index were also the ZIP codes with the lowest life expectancy in the county and the ZIP codes where COVID hospitalizations and deaths were disproportionately higher than in counties with similar populations but less vulnerability for chronic diseases.

They're also counties with a higher concentration of Black and Hispanic residents.

For example, the 75204 ZIP code has one of the lowest vulnerability indexes. It includes neighborhoods like Uptown and Oak Lawn. There are about 32,032 people who live there. According to DCHHS, there have been 10,199 reported cases of COVID-19 in this area -- 284 of these residents have been hospitalized with the virus, 57 were admitted to the ICU and 29 peopled died.

Dallas County's 75241 ZIP code has about 30,864 residents. Despite having fewer people, the area has had 10,418 reported COVID cases -- 936 residents were admitted to the hospital as COVID patients, 201 of them were put in the ICU and 125 of them died.

There is an undeniable link between chronic illnesses and the impact of COVID-19 in these communities, with serious illness and death being the most alarming outcome.

While some of these conditions are genetic, a majority of them are linked to lifestyle.

In fact, for most of these conditions, the CDC's top three tips for avoiding them are to avoid smoking, eat a healthy diet and exercise. The health organization even listed physical inactivity as a risk factor for COVID-19.

"They don't always prevent it in everyone, and they don't always stop the progression of these diseases but they can certainly reduce the risk," Estelle said.

Estelle said healthier living can also decrease the amount of medicine people with chronic conditions need to take to treat those conditions.

While there are safety barriers to exercising outside in some neighborhoods and areas in North Texas that are food deserts, voids of grocery stores selling fresh food, there are a number of socioeconomic factors that contribute to this disparity. There is also an opportunity for people who may not be able to move neighborhoods to take ownership of health and improve their outcomes.

There are also groups working to break down those barriers.

Theo Murdaugh created the Zone Fitness Training Run Club in Dallas in March 2020. The group meets on Wednesday nights in Los Colinas and on Saturday and Sunday morning at White Rock Lake for what it calls a "social run".

“We’re running with a purpose, and we make sure every time someone comes out here we start them out with a 5K and, heck, they end up working their way by themselves up to a marathon, so it’s just been massive," Murdaugh said.

The running club is almost entirely made up of Black runners, making them unique in the North Texas running community.

"When we show up to these races, people look at us like, oh we’ve never seen this before. This is different," Murdaugh said.

In 2022, 22 ZFT runners ran their first full marathon, and 15 ran their first half marathon.

"We got people who, two years ago, probably couldn’t even run a quarter of a mile and they’re going their second…third marathon," Murdaugh.

He said his group is "inspiring," as he watches people of all shapes and sizes dedicate time and hard work to reaching goals they never knew they had. He said he also sees the ripple effect in how his members approach their health.

"They’re doing their own research," Murdaugh said. "They’re finding out how their bodies tick. We’ve had people with weight issues…heart issues…all kinda of stuff. They want to run so bad. Now, all of a sudden, that’s inspiring them to go to the doctor and get checked out to make sure they’re healthy enough to run. It’s really given people the opportunity to take their health very, very seriously, especially for Black men."

And as the group grows each week, with some meetings drawing more than 100 runners, the feeling of healthy community does too.

"That is public health," Estelle said. "They are doing an extension of what Dallas County's health department and all of our public health colleagues are doing, and they're doing it in a grassroots fashion out in the community."

Estelle said she hopes the group continues to grow, as research shows public health initiatives are most successful when they are created by, and for, their own communities.

The pandemic glared a light on a number of health issues that already existed in North Texas, and while substantial societal change is likely needed to address them in full, there are things everyone can do to be healthier and live longer.

"What you do matters," Estelle said. "Your choices matter, and they make a difference. Start small. Pick one thing."