VENUS, Texas — The stories you hear in prison can sometimes make you shudder.

“I’m an alcoholic. I’ve been an alcoholic for a while. I should have known that if I made that choice to drink, it could bring me to prison,” one inmate said at a recent meeting.

But at the Estes Unit, off Highway 67 near Midlothian, some of the most compelling stories aren’t always from inmates.

“Yesterday, was three years since we buried our son. So, it was a tough day,” said Susan Polson, 61.

Her son, T.J. Antell, was murdered three years ago.

“I can’t go past a Walgreens without seeing my son lying there with a sheet," she said. "And all I see is his feet, and no one will let me go near him."

In 2016, Antell tried to intervene in a domestic violence situation after a man opened fire on a woman who worked at the Arlington store.

But the 22-year-old husband and U.S. soldier, Ricci Bradden, turned his gun on Antell, a Good Samaritan, and killed him.

“One of the things I told them, I don’t want their sympathy," Polson told WFAA. "I don’t need their tears. I just wanted them to listen."

She visits the prison as part of a program called Bridges to Life, which focuses on restorative justice.

“She really touched me,” said Rashod Allen, an inmate, after listening to Polson's personal tragedy.

He volunteered to become part of the most recent Bridges to Life class at this unit.

“I had a friend drag me," Allen said. "He was like, ‘This is a good program.’ I was like, ‘Not another program.’ But I took the initiative and got started and once I got started it was full steam ahead."

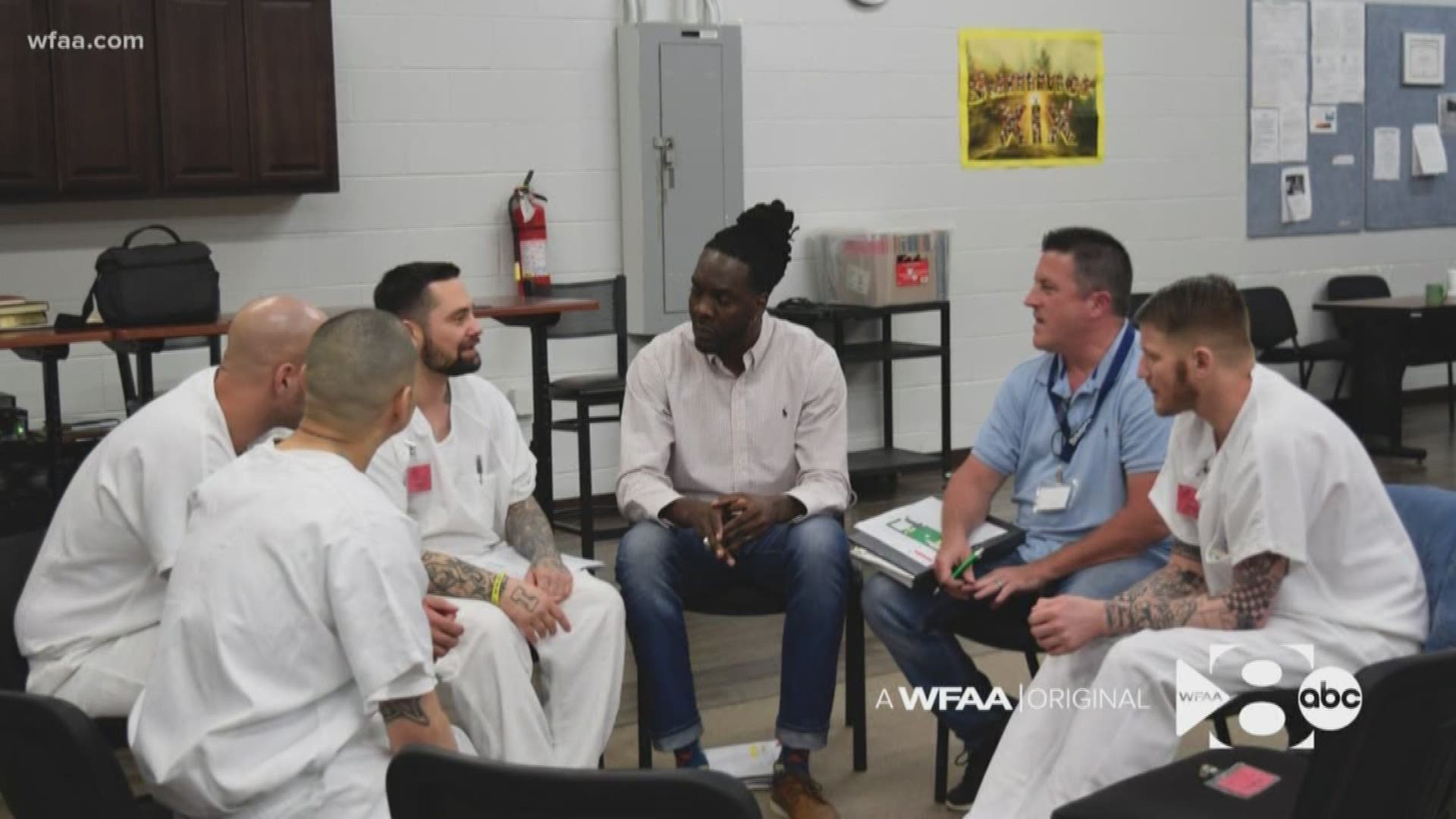

Bridges to Life is not a prison ministry and doesn’t teach a trade. Instead, the program connects 10 offenders with two volunteers for a couple of hours a week for three months.

Volunteers don’t lecture, they listen.

“The old idea of lock them up and throw away the key has created a system of recidivism and violence which is self-perpetuating,” said Charles Fisher, 51, a regional coordinator for Bridges to Life. “This new model of restorative justice helps the community come inside the very walls we have placed them to show them the error of their ways.”

Fisher knows the impact of Bridges to Life. He is a former inmate who, while serving his sentence, participated in the program and has since become the organization’s first staff member who is also a graduate.

“It gives you an understanding of what they went through. Not only that, it gives you more empathy and lets you sympathize with what they went through,” Allen explained.

Hearing from crime victims helps inmates discover who they’re hurting.

“Before Bridges to Life, I justified my crimes of selling drugs,” said Vincent Corley, 35, who has 10 months left on his sentence. "I wasn’t robbing anybody, hurting anybody. [But] my crimes don’t affect just the people I’m selling drugs to. It affects their families, the whole community at large."

“I am a crime victim myself. Unfortunately, my mom was murdered and my dad was the offender,” said Jim Buffington, the chief operating officer of Bridges to Life. “He hired two of his employees to murder my mom, two brothers, for insurance money. He wanted to be rich, free and single was his motivation.”

His experience as a crime victim and the son of a felon helps him relate to both the victims who volunteer and the inmates.

“We’re trying to get the offenders to answer the questions on accountability, responsibility or forgiveness or reconciliation,” Buffington said.

Recidivism is one way to measure results of Bridges to Life. On average in Texas, about 22% of the inmates who are released either commit crimes or violate parole and return to prison.

But those who enroll in Bridges to Life have a better chance of staying out of trouble after they leave the system. The recidivism rate for this program is 14%.

Since it began in Texas in 1999, more than 45,000 inmates have gone through the Bridges to Life program at dozens of prisons across the country.

“I was able to express what we’ve been through as a family. What I’ve been through as a mom to these inmates. They need to understand what they’ve done to somebody. There is a victim,” Polson said.

Prison was the last place Polson expected to find some peace.

It is a painful story that helped her heal and inmates understand.

“We’re not bad men. We made bad choices,” said Mark Cadiss, an inmate.

To volunteer with Bridges to Life, click here.

WFAA originals:

- 80 people went to Dallas emergency rooms 5,139 times in a year — usually because they were lonely

- After childhood stroke, Hebron senior stuns classmates at graduation

- 'It's a race against time': Rare chronic pain condition doesn't stop this woman from running marathons

- Tearing down walls: Fourth graders prove what’s possible by bridging differences, building friendship